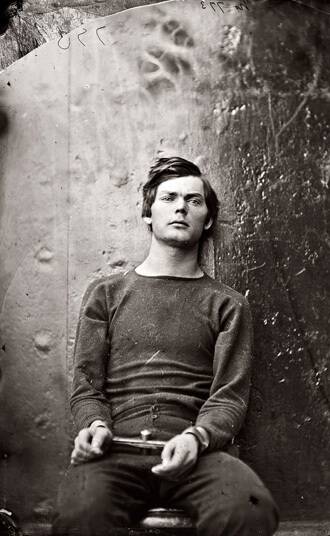

Dr. Deborah Persaud of the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. | AMFAR.ORG

Doctors and researchers say they have cured a Mississippi infant born with HIV with an aggressive treatment regimen that began a day after birth. The triple-drug combination was continued for a year and a half until the mother stopped bringing the child in for treatment, according to the New York Times. When the child was next brought in five months later, there were no signs of infection. The infant is now two and a half and is free of HIV.

If follow-up study of the case is able to confirm that the child was in fact infected and is now free of the virus, it would be the first such instance of an infant being cured. The baby received care at the University of Mississippi Medical Center and went through a battery of tests conducted by researchers at the University of Massachusetts and Johns Hopkins University. Their work was funded by amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research.

Dr. Deborah Persaud from the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center presented study findings about the child at the March 4 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Atlanta, though the report has not yet received peer review.

The Times quotes Dr. Daniel R. Kuritzkes, chief of infectious disease at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as saying the child’s HIV status at birth is the primary question that must be established. In the US, children born to HIV-positive mothers can almost always be protected from getting infected in the first place if the mother receives antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy and the child is given a course of treatment for roughly six weeks after birth.

In the Mississippi case, the pregnant woman received no prenatal care and did not know she was HIV-positive until the time of birth.

Prenatal care of HIV-positive women in this country has been sufficiently effective that only about 200 HIV-positive babies are born each year. Worldwide, however, that number is roughly 330,000, according to the United Nations.

Researchers are looking at the possibility that the Mississippi infant was cured because the infection had not yet progressed to the point where it found reservoirs in the body where it could protect itself from the effects of the antiretrovirals. Such hidden reservoirs typically prevent HIV from being eradicated from the body of those infected, a fact that raises doubts about whether the Mississippi results have potential benefits beyond cases of infected newborns.

An adult living with HIV, Timothy Brown, was reported to have been cured of his infection in 2007 when, in the course of treatment for leukemia, he received a bone-marrow transplant from a donor genetically resistant to HIV infection.