Closeted Romances

Silent stars, a shy director, and the beauty of Bucholz

Wings Theatre has one of its best productions in “Through a Naked Lens,” the true romance between silent star Ramon Novarro (JoHary Ramos) and his press agent, Herbert Howe (Stephen Smith). George Barthel’s script is both historically and emotionally accurate, excellently researched, with a real love of the era, and the direction by Richard Bacon and L.J. Kleeman moves things along with amazing scope.

Novarro is the role Ramos was born to play, as he possesses a like ripe handsomeness and melting sincerity—not to mention the best buns on Off-Off-Broadway.

“I feel so honored to be playing Novarro,” he told me. “I can relate to him being a former dancer, struggling in New York, Catholic, with a lot of family he took care of. I read a lot about him and saw his films, “Scaramouche,” “The Student Prince,” the ending of which is fantastic, and, of course, “Ben Hur” [the film that shot Novarro to superstar status, making him the DeCaprio of his day]. As we say in Spanish, with all the beautiful support I have here, I feel like a chicken in his own backyard. But it’s very painful to me to think about the way Novarro died.” The star was beaten to death by two hustlers in his Hollywood home in 1968.

Heather Murdock was potently poignant as Alice Terry, Novarro’s co-star in “The Prisoner of Zenda,” and said, although she had never heard of the actress before, “I fell in love with her, and much of my research came from Howe’s original articles in period fan magazines.” When I mentioned that the aristocratic Terry was a blonde, as opposed to Murdock’s chestnut locks, the actress said, “Actually, Alice had my same hair color. Rex Ingram [Terry’s director husband] insisted she wear blonde wigs. I didn’t want a wig, so I cut my hair and style it like the ‘20s. It takes an hour, but I prefer that.”

In the audience was author Lawrence Quirk, whose Uncle James Quirk, the editor of Photoplay magazine, was played onstage by Shay Coleman.

“I didn’t expect this to be so moving,” Quirk, the author of 35 Hollywood books, said. “It was sad that Howe died so young [after his breakup with Novarro, in 1959, at age 63, completely unnoticed by the press in which he had once been such big player]. But this actor who played him tonight has a real X-factor and I think should be a star.”

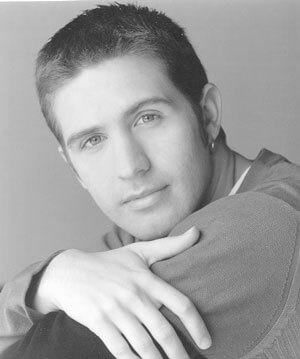

Stephen Smith was flattered by such fully deserved encomiums and praised his production team for the amount of research the actors were given.

“Howe’s beautifully written articles really helped me understand him, and the day to day lives of these incredible Hollywood people,” Smith explained. “I just moved back to New York from Las Vegas, where I was in ‘Saturday Night Fever.’ I went to school in Knoxville, Tennessee and even worked at Dollywood, but New York is where I want to be for work and I’m looking for an agent.”

Sign the boy up—he’s dynamite!

Smith agreed when I said I found the play far more moving and powerful than the highly lauded but pallid “Brokeback Mountain,” another impossible romance between closeted men.

“If gay men had been more involved in that film,” he said, “I think they would have taken things much farther.”

Too obviously a gay film made by straights, I’m glad for the “Brokeback’s” commercial success in the heartland and the way it may seriously change negative attitudes, but to call it an historic work of art, as many are doing, is a bit much.

At a New York Public Library Young Lions event last month, Director Ang Lee was asked about the movie’s sex scenes. Lee, a bit disgruntled that “Brokeback Mountain” author Annie Proulx, who had roped him into attending the event, didn’t herself show because of what she described to him as “an important elk run in Wyoming,” said, “I’m very shy. So, especially in those scenes, I just let the actors do what they want.”

There were other problems I had with the film, apart from the men’s interaction, which feels at once like a gruff, yet sanitized version of gay sex, only slightly PG-rated. First timers don’t just jump each other’s ass like that – what happened to foreplay and the exploration of that forbidden mystery of mysteries, the penis? When Heath Ledger, stalwartly butch-to-the-point-of-inertness, suddenly grabs Jake Gyllenhaal in a furious kiss right in front of his house, with his wife watching from the window, I found it simply unbelievable. Married closet cases, especially in the early ‘60s, especially in cowboy country, surely would have been more circumspect. Of course, this might have worked as a deliriously cinematic moment had, again, the director not been so tentative.

So wife-y (Michelle Williams) gets to suffer stoically through the years, in age-old noble Hollywood wife fashion, while Gyllenhaal’s physically similar spouse (Anne Hathaway) turns trashy-Texas, with blondined nearer to heaven/nearer to God hair, both of them facile female stereotypes. I found much of the regional attitude toward the people in the film condescending, with the entire West coming off like some redneck/bigot-populated circle of pure hell.

Director Lee didn’t seem pleased when I complimented him on the shepherding scenes, with their awesome Eye of God camera angles. What can I say? Those were the best, authentic parts of the movie—with the sheep giving the most convincingly natural performances of all.

Like most of Lee’s films, “Brokeback” dawdles atmospherically and is just too damned long. He could definitely learn something about pacing from the master, Billy Wilder, whose 1961 comedy “One Two Three” is playing at Film Forum. A frenetic farce set in a Wall-divided Berlin, it features a rampant James Cagney as a Coca-Cola executive who must deal with an equally voracious Horst Bucholz, decrying him as “capitalistic scum.”

“Commie punk!” Cagney yells at him, with an intensity that reveals the onset enmity these actors shared. Bucholz, who definitely possesses enough X-factor to make gay males of any age sit up and say, “Who the hell is that?” was determined not to let the older actor dominate their scenes. Kevin Lally, author of the definitive bio “Wilder Times: The Life of Billy Wilder” (Henry Holt), interviewed co-star Pamela Tiffin, who told him that Bucholz was naughty, but so charming and handsome that you forgave him.

“He would try to rotate Cagney, so that Cagney’s back would be to the camera and Horst would be onscreen,” Lally quoted Tiffin as saying. “You cannot do that to an old hoofer like Cagney or to Billy Wilder. I didn’t understand. All I knew is that when I worked with Horst, I was rotating like a merry-go-round.”

Lally also interviewed a feisty Bucholz in 1994 who, when Lally complimented him on appearing in a classic Billy Wilder film, snorted, “What do you mean? I’ve been in several classics!” But Bucholz did tell him that one morning he came in early to the Bavarian studio and heard “Tacka tick tack… And behind some wall, I found Jimmy Cagney soft-shoeing. I said, ‘What the hell are you doing this for?’ And he said, ‘Oh, it helps me get that dialogue out as fast as I can.’”

Contact David Noh at Inthenoh@aol.com.

Actor Stephen Smith demonstrates an X factor in his portrayal of press agent Herbert Howe in “Through a Naked Lens,” a play now on stage at Wings Theater that explores his relationship with actor Ramon Navarro, which spanned three decades from the 1920s.

Heather Murdock was potently poignant as Alice Terry, Ramon Novarro’s co-star in “The Prisoner of Zenda,” in “Through a Naked Lens.”

Bucholz Horst, in a scene from Billy Wilder’s “One Two Three,” now screening at Film Forum, was described by co-star Pamela Tiffin as naughty, but so charming and handsome that you forgave him.

At a New York Public Library Young Lions event in December, “Brokeback Mountain” director said of the film’s moments of passion, “I’m very shy. So, especially in those scenes, I just let the actors do what they want.”

gaycitynews.com