BY ED SIKOV | Thank you, Jesse Singal of New York Magazine, for writing “Why Arthur C. Brooks Is Wrong About ‘Victimhood Culture,’” a persuasive rebuttal to Brooks’ obnoxious op-ed in the New York Times.

“Victimhood culture” has now been identified as a widening phenomenon by mainstream sociologists,” Brooks bleated. “In all cases, [the victims] treat people less as individuals and more as aggrieved masses.” Oh I get it: they’re Commies.

Singal had none of it.

“There’s a great deal of caterwauling at the moment about how everyone — particularly students, and particularly minority students — is just too damn sensitive,” he writes. “Society is devolving into a game of offense one-upmanship, people argue, and it’s gumming up the works of what had been a more vibrant and honest discourse.” Singal then proceeds to dismantle Brooks’ assertions one by one. The “mainstream sociologists” Brooks trumpets number precisely two, their output on the subject a single journal article. “And presidential candidates on both the left and the right routinely motivate supporters by declaring that they are under attack by immigrants or wealthy people,” Brooks announces, to which Singal replies, “You could drop this into any column about American politics published at any point in the last 150 years or so and it would fit. It has no bearing on anything.”

Attacking college students, especially minority college students, is all the rage. The wingnuts had a field day –– field month is more like it –– over the brouhaha at Yale after a lecturer wrote an email supporting the right to wear offensive Halloween costumes. A lot of students expressed outrage. Their critics derided them as oversensitive brats.

I related to the story –– from the professor’s side. I’d written a similar post on Facebook. Halloween is all about upsetting people, I airily opined. So what’s wrong with wearing an offensive costume? Some FB friends agreed with me. My post got lots of “likes.” One responder, however –– a former student who is now a good friend well beyond FB –– wrote, “Is upsetting sensibilities necessarily the same as being offensive? I say no, and think conflating the two is willful blindness that is more towards jerky than intelligent boundary pushing.”

I found his point hard to argue with, offered a lame reply, went on my merry way, and faced no consequences at all because nobody gives a rat’s ass about what I post on Facebook. The Yale lecturer’s message, however, was easily reproduced and widely disseminated. And bitterly attacked. She ended up resigning from Yale. Those who had forums to air their outrage gave rats’ asses galore. The New York Daily News went so far as to headline a story “Mob Rule at Yale.” Mob? Let’s not mince words; the paper might as well have called the protestors “uppity Negroes.”

“Safe spaces.” “Microaggressions.” “Trigger warnings.” These terms quickly exploded in the media, mostly to derision. The final straw was a protest at Oberlin College over what some students condemned as the campus food service’s “appropriation” of other cultures’ cuisines –– specifically, a sloppy rendering of a Vietnamese sandwich called bánh mì and a ptooey version of the always questionable Chinese General Tso’s chicken.

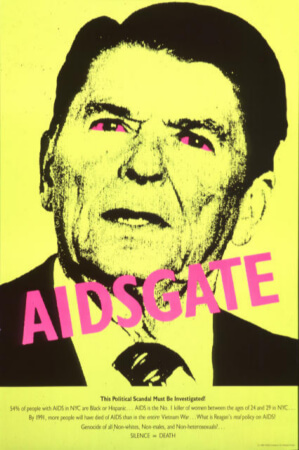

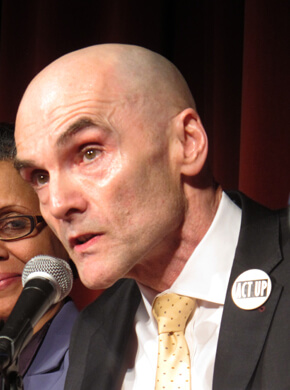

By claiming that bad food was also cultural appropriation, the students were tossing around sociological concepts they’d learned in class along with their unfinished dinners, and for a lot of people, that was too much to stomach. VanityFair.com, Slate, and other media outlets joined the predictable New York Post in ridiculing them. Even two of the smartest gay commentators out there climbed aboard the backlash express. On Facebook, Peter Staley, the longtime AIDS activist and Oberlin alum, deemed the protesters’ reaction “hypersensitivity overdrive,” and the equally brilliant Josh Barro –– also on Facebook –– declared that “what colleges desperately need is some administrators and faculty who feel permitted to tell students to stop whining.”

Telling students to stop whining is like telling them to stop jerking off. Unlike (most) wanking, though, whining is a communal activity and is thus the most popular sport on campuses around the country. I practically lettered in it.

The real point is that students have the right to be wrong. Sure, I find the idea of “trigger warnings” –– little tags that colleges now stick on syllabuses, books, films, plays, anything that might “trigger” a bad reaction from a student –– to be totally antithetical to learning. If I were still teaching Sex and Gender on Film, the class I taught at my alma mater, Haverford, from 1995 to 2004, I’d have to stick a mess of boldface trigger warnings all over the syllabus to cover my incessant attempts to –– as my friend put it on FB –– upset students’ sensibilities in every lecture.

As for culinary appropriation, it’s critical –– to me, anyway –– not to conflate bad food with cultural appropriation. Most college dining services can’t get beef stew right. Is it any surprise that the bánh mì was awful?

What all the outraged commentators disregard, though, is that one of the aims of a college education –– particularly a liberal arts education – is to encourage students to speak their minds and stand up for themselves, even (or especially) when what they say and do irritates the grown ups. No, more than that –– when what they say and do strikes older folks as silly, overblown, or just plain wrong. College students are trying on new ways of thinking. And we all learn by trial and error. Especially error.

I was enraged when a number of women in my class walked out of a required screening of Kathryn Bigelow’s “Strange Days” because of its especially disturbing rape sequence. To me, they had no choice but to watch the whole film; it was an assignment, just like dirty Chaucer in English Lit and some incomprehensible problem in Organic Chemistry. But to them, they had no choice but to walk out. We discussed it, both sides aired our positions, and (I think) we all learned from the experience, though I still feel the need to point out the irony of women walking out of the only film on the syllabus that was directed by a woman. (Why was the rape scene particularly upsetting? Because Bigelow filmed it from the victim’s point of view.) In the end, I decided that the fight wasn’t worth it. I switched out “Strange Days” for another film the following year. I think it was “Videodrome.” Which they hated even more.

Student protesters have seemed like spoiled brats before. That hoary charge was leveled against students who protested the war in Vietnam, often scorned as cowardly draft dodgers. What distinguishes today’s protesters from Vietnam War demonstrators is that the loudest ones are minority students who aren’t just shutting up and taking whatever their colleges hand them with the expectation that they’ll be oh so grateful. We should applaud them for sticking their necks out and resist the urge to chop their heads off.

LGBT, African-American, Asian-American, Latino, and other outnumbered and/or outpowered students demand “safe spaces” for a reason: they feel genuine if subtle hostility emanating from privileged students and, less obviously but even more painfully, the institutions themselves, even if it’s just a roll of the eyes during a discussion of race or gender or the common assumption at elite colleges that students from crummy, poor public high schools should naturally be able to compete immediately and on an even plane with the highly advantaged prep school graduates who have suddenly become their peers. Parents pay Phillips Exeter almost $47,000 a year to provide precisely those advantages. To turn around and deny the privilege and its painful effect on the underprivileged is inane.

These –– by the way –– are microaggressions: displays of inherited power that are small in performance but vast in effect.

Safe spaces are necessary. I explicitly told my students that my office was a safe space for LGBTers –– a place in which they could say anything without fear, and as a result I lost count of the number of students who came in, came out, and told me I was the first adult they’d let in on their secret. It took courage for those students to walk in and open up to a prof about their sexuality. If I hadn’t explicitly carved out the space in which they knew they could speak freely, they probably wouldn’t have confided in me. And their college experience would have been a little less meaningful and a lot more impersonal.

It’s easy to mock an undergraduate for arguing that the dining hall’s bánh mì is an offensive cultural appropriation by the world’s only superpower against Southeast Asia. It’s a lot harder to answer the question of why he’s so angry, let alone to face the issue of why his complaint generated such a tsunami of fierce contempt among those whose voices wield far greater authority than his. Before he spoke up, that is. Maybe his detractors just don’t like the competition.