Actor Stephen Spinella stretchesJean Genet’s Elle to dramatic heights

Jean Genet is no stranger to God. Throughout his plays he consistently explores the ways man creates God and worships him to give meaning to his existence. At the same time Genet draws attention to man’s creation of God as an ironic cry against the state of nothingness that he believes is intrinsically feared above everything else. In Elle, a little known play—never before produced in English—Genet takes his construction deconstruction of God to new heights, or at least his earthly representation, the Pope.

Elle was never performed during Genet’s lifetime, but this summer it is the play everyone in New York is buzzing about. The first production of Art Party, a new company formed by actor Alan Cumming, director Nick Philippou, and producer Audrey Rosenberg is being presented through July 31 at the Zipper Theater. Fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, an Art Party associate, created the costumes. Cumming wrote the adaptation, and is starring as the Pope.

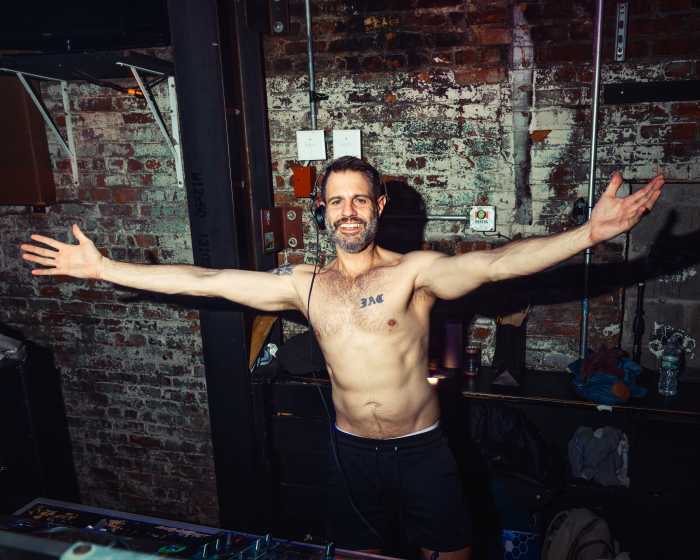

Stephen Spinella, best known for his two Tony award-winning performances in Angels in America (he won in successive years for each part) plays the pivotal role of The Usher, the Pope’s assistant and press agent. Spinella spoke with Gay City News in anticipation of Elle’s opening.

“Grammatically and socially shocking,” is how Stephen Spinella describes Elle. The title is the French pronoun for “she,” and Spinella points out that the French construction for Pope is Sa Sanctité, a feminine construction, which was the play’s original French title. Throughout Elle, the Pope is referred to as “she,” which was—and presumably remains—“grammatically and socially shocking.”

Throughout his writing, Genet balances the sacred and the profane, demonstrating, often with great lacerating comedy, the dichotomies between the huge, iconic characters we create as a means to create meaning and man’s more bestial nature. As one character says in The Balcony,“our function will be to support, establish, and justify metaphors.”

The main metaphor in Elle is classic Genet, something that will be interpreted as reverent by some and blasphemous by others. The idea is that the Pope, and hence God, may not exist outside of man’s imagination. The story concerns a photographer who has been sent to the Vatican to photograph the Pope. The belief is that the world needs a perfect image of the Pope with whom they can identify and through which they can presumably express their faith. During the photo session, the Pope attempts to tell the photographer that he is not his image, and goes further to say that he, the Pope, does not in fact exist at all.

In discussing the meaning and relevance of the play, Spinella spoke feelingly of the current state of celebrity and image that permeates our culture. He notes that the play “presages the coming obsession with image that is part of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

“[Today] we are completely overwhelmed by image,” he says. “There is something profound about the pernicious nature of image and idolatry in the play. The Pope comes in at page 20—and it’s only a 51–page play—and we meet this guy who is incredibly disturbed by the proliferation of ‘image’ and the destructive quality on himself and who he is.”

A great deal of the tension in the play is derived from the Pope’s concern about the overwhelming reality an image can hold. As the Pope’s usher, Spinella is both the caretaker and prophet of the Pope’s image. As a result, we see “two men in a powerful relationship with each other having trouble getting to the place where there is love,” says Spinella. In large part, he adds, because there is the tension between one person who insists on the image and the other person who wants to be a human being.

Spinella likens this to broader issues concerning the role images play within our culture. He believes that today image can “destroy humanity—as in the play with the Pope—or with certain movie stars. It can destroy their interior life and their sense of who they are as a person. They become—or attempt to become—what the image represents, and they lose the connection to their own humanity. It’s not just movie stars, anyone who attempts to live an image rather than a life is at risk for the kind of dislocation the Pope experiences in the play, or presumably the shock and despair felt by those who have believed in the image and discover it is not real.”

For queer audiences, Spinella thinks the play may have special resonance. “Alan, Nick [Philippou, the director] and I are all gay and coming out of certain gay politics. We couldn’t really do this [play] till now and have it looked at and thought about seriously.” Spinella says that is largely because of a cultural consciousness about gay politics, a growing understanding and awareness of ideas, and the understanding of image in its role in our identity and social constructs. “Our generation has lived through ‘image,’” he says.

In his plays, Genet makes huge demands of his audiences; he engages in both artifice and argument and thus his work is not readily accessible as entertainment. His work is not often produced in the current economy outside small companies. With Genet, as with Strindberg, producers do not see “easy money” when contemplating a production. For actors, however, he offers a chance to explore their craft in ways that traditional commercial theater—and forget movies and TV—does not. It is not surprising, then, that the chance to do a previously unseen Genet play in New York would attract some high power talent—even if they are all working for little more than car fare.

“Occasionally you get the chance to do these things, and you cross your fingers and hope it will work. This has been an incredible process. It’s been one of the most open rehearsal processes I’ve ever had.”

He adds that this is important not just because of the relatively short amount of time to put the production together but the chance to work with good actors. Spinella describes the interaction among them as “ego less vigilance. It’s very rare, and you don’t get to do it that often. We have camaraderie, and everyone had to put their two cents in about everything… or we couldn’t do it in three weeks. To be actively involved with all these exciting minds has been a really sublime experience.”

Spinella’s enthusiasm is matched by that of critics.

“Mr. Spinella turned The Usher into a chemically exact fusion of ascetic gravity and romantic rhapsody,” wrote Ben Brantley in The New York Times.

Genet is certainly one of the densest playwrights of the 20th century—in this case, “dense” meaning packed with substance. As philosopher and comedian, Genet’s writing is always an exploration and seldom tidy. He consistently uses the theater, its inherently false constructs, and the necessary acceptance of metaphor by the audience as means of highlighting the absurdity of behavior in other aspects of life, amplifying the notion that pervades his work: that without belief, man is nothing, and at the same time he challenges the validity of belief.