“I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” a 1982 documentary about gay writer James Baldwin and his participation in the civil rights movement, isn’t nostalgic for the ‘60s. Baldwin is too clear-sighted about the violence and racism of the period; in fact, he says it led to his disenchantment that America could be reformed. But its road movie structure, tracing Baldwin’s travels in the south during 1980, is also a trip through time. Directors Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley nimbly edited together what was present-day footage of Baldwin’s conversations and public appearances, performances by musicians in several cities, and archival news clips. Time and time again, this juxtaposition of past and present leads Baldwin to the conclusion that nothing has really changed: America’s racism has gotten sneakier at concealing itself behind a shinier façade.

Film Forum has tied the re-release of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” to a two-week retrospective of documentaries about Baldwin. Raoul Peck’s “I Am Not Your Negro,” which grapples with Baldwin’s writing about American film, was a substantial hit at the same theater seven years ago. Around this time in 2023, Film Forum presented a program of three shorts, “Baldwin Abroad.” His star has risen dramatically in the 21st century, but “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” presents him at his most uncompromising, offering the opinion that Martin Luther King Jr’s official memorial is a useless attempt to make the lessons of the past distract for the present. In his eyes, it’s “just as irrelevant as Lincoln’s memorial.”

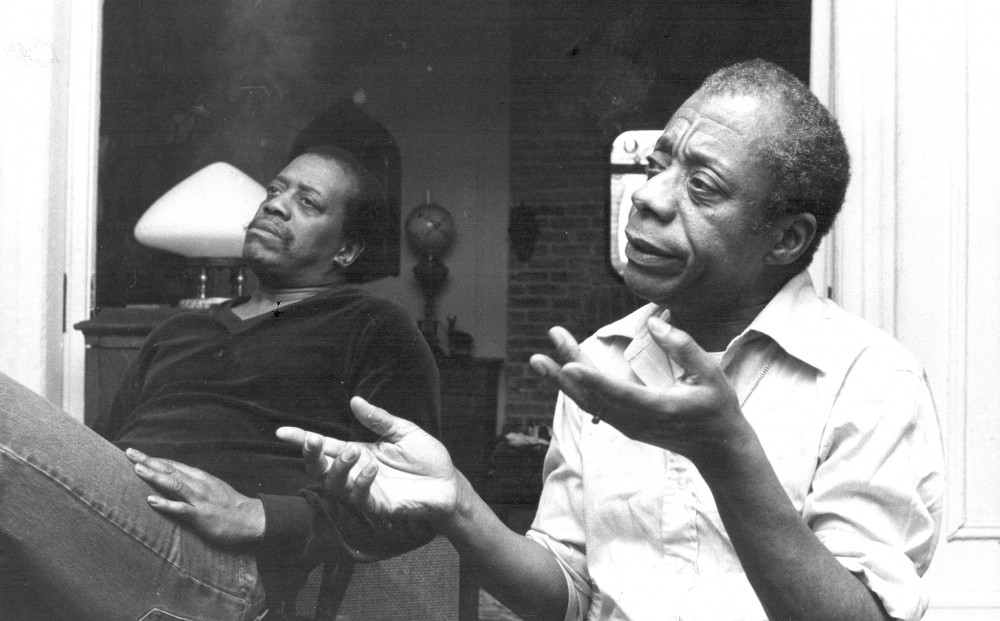

Fontaine made several documentaries about African-American jazz artists, including Sonny Rollins, Rashaan Roland Kirk, Ornette Coleman, and Art Blakey. (He filmed other musicians, from John Cage to Johnny Rotten, as well.) A bluesy cover of the Marvin Gaye song from which his film takes its name plays over images of Black men in jail. The editing of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” adopts a musical structure, giving variety to talking-heads interview footage. The documentary adopts a form of call and response, where the past speaks back to the present. It emphasizes community, rather than treating Baldwin in isolation. Baldwin is always filmed talking with at least one other person, mostly old friends from the ‘60s. His writing isn’t ignored, since he’s shown attending a literary conference in Newark, but his ideas are given more attention than his storytelling. At the end of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” he visits a Florida beach with Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe.

Although Fontaine was a white Englishman, his co-director Hartley was an African-American woman who began as an actor.

Baldwin seems more at ease than he might be in front of a camera solely helmed by a white man. Their film avoids making Baldwin palatable for a liberal audience. He ends the film by saying, “I don’t expect anything from them (white people), I expect a lot from us (Black people.)” Throughout, he and his friends suggest that the civil rights movement was essentially a failure that allowed a few Black politicians and businesspeople to prosper — “so many tokens,” in his words — without helping the poor. Not everyone in the film agrees entirely with the despair underlying Baldwin’s perspective — Charles Sherrod shows off the 4,000-acre farm where he plans to establish a worker’s co-op – but a great weariness that the promises of the ‘60s didn’t pan out fills the film.

Since his death, Baldwin has become one of the most iconic gay writers of the 20th century. His queerness is central to the reasons he’s valued now, but documentaries about him have tended to erase it. Otherwise first-rate, “I Am Not Your Negro” never brought up his sexuality. While Baldwin speaks at length about how life hasn’t really changed for Black Americans, one wishes Fontaine and Hartley had asked him about his perspective on gay life. This is an absolutely essential documentary, particularly for anyone wondering why the BLM protests of 2020 didn’t lead to substantial change in American life. It fills in a perspective sanitized by Hollywood and mainstream history, where Martin Luther King is reduced to the “I have a dream” speech and treated as a figure who sacrificed himself to end — or at least ameliorate — American racism.

The continuity of the problems “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” shows, especially income inequality, is glaring. Yet it takes nothing away from its immense accomplishments to wonder what else we could’ve learned if it were curious about Baldwin’s experience as a Black gay man.

“I Heard It Through the Grapevine” | Directed by Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley | The Film Desk | Opens at Film Forum Jan. 12th