Gay governor, Jim McGreevey, comes clean, speaks out

In “The Confession” McGreevey airs his dirty linen in publication and earnestly attempts to deconstruct his former self, which was “pathologically attached to ‘having a public.’” In fact, he displays a distinctly oral fixation in his pursuit of public service, no pun intended—“My ego demanded recognition…my ego—that was the dopamine receptor for my addiction, the thing that needed feeding.” Enter Golan Cipel, who was willing to nourish that appetite like a male Lady Macbeth. The saga of the governor who lost governance over himself calls to mind another scandal, another long literary mea culpa by a prominent married gay man, and author of the epigram, “The only way to get rid of temptation is to yield to it.”

Oscar Wilde laid his soul bare in his lengthy essay, ”De Profundis,” written from his cell in Reading Gaol, where he suffered two years of inhumane deprivation and hard labor for acts of gross indecency. Ostensibly addressed to the aristocratic wastrel, Lord Alfred Douglas, much of the essay displays Wilde’s late conversion to Roman Catholicism—already a strong latent tendency, which was, no doubt, expedited by his first-hand association with public crucifixion. McGreevey, takes a similar tack in “The Confession,” and reveals his deeply ingrained Irish-American Roman Catholic roots.

“I rejected a political solution to my troubles,” he observes about his sensational resignation, and took the more painful route—penance and atonement, the way to grace.” Of course, to compare McGreevey’s case to Wilde’s is invidious, insofar as it involves neither a literary genius nor a brutal prison term. Wilde lived at a time before the concept of the closet even existed—because the concept of a gay person didn’t exist. Bosie Douglas wrote about the “the love that dare not speak its name” because there was literally no way to talk about this phenomenon. Wilde heroically put himself out on the line when no one else would, and he paid a very high price indeed. Even while negotiating his own Via Dolorosa, it’s clear that McGreevey, in the spirit of American self-improvement manuals, is intent on his ordeal having a salutary ending—and his $500,00 book deal appears to be a good beginning—hardly a cross to bear!

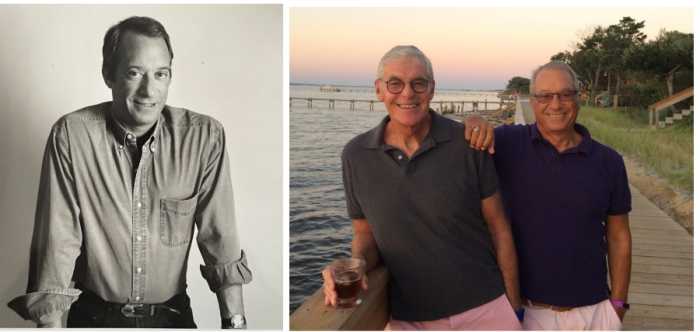

The memoir is an honorable effort, consistently engaging and thoughtful. The only cringe-inducing chapter involves his stay at The Meadows, a clinic in rural Arizona for patients with substance addictions or suffering from trauma. In what might be called his “Brokeback Come-back,” he is also in a new, admittedly loving relationship, sharing a stately mansion in Plainfield, New Jersey with Mark O’Donnell, an Australian financial advisor, “who has shown me the love I was looking for all along.” McGreevey presently works as an education advisor, and to help children and teen-agers who suffer from violence and discrimination.

When McGreevey fell, he fell like a California redwood. He tells of “courting discovery” in “our fish bowl existence,” and stealing furtive kisses with Golan in the library of Drumthwacket, the historic governor’s mansion in Princeton. Slipping away one night in his jogging suit to visit Cipel’s apartment, he observes, “…He greeted me in his briefs. ‘Did anybody see you?’ he asked, closing the door quickly. We kissed hard. I was totally in love with this man. He loved everything I loved. Politics never bored him. He loved strategy and demographic analyses. He loved power, philosophy, justice… He led me to his bedroom, past photographs of him and his naval crew and a set of painted toy soldiers, posed in some famous battle formation. Israeli folk music played on the stereo. He undressed quickly and jumped into bed.”

“To get what I wanted after so many years of denial was almost too much for me. Our first times together burned so fiercely in my mind I could hardly recall them even as we were still lying together. I’ll never forget the look of trust in his eyes and the dead weight of his vulnerability in my arms. But I was like a kid on his first days of drivers’ ed, too thrilled to be behind the wheel, unfamiliar again with the roadways I’d known all my life….”

Not long after this impassioned stretch of their clandestine affair, McGreevey would hit a serious pothole and end up losing control of the steering wheel. Turns out, the baby-faced Golan wasn’t really a team player, but a shifty schlemiel with delusions of grandeur and a tendency toward blackmail. The rest is history, along with McGreevey’s long cherished hopes of a future in politics. Later, his wife, Dina would accuse him in legal papers of “courting her, and ultimately marrying her, for purely political reasons.”

When forced to publicly declare his infidelity and relationship with the extortionate Cipel—who first demanded $50 million, but would settle for five—McGreevey’s statement, “My truth is that I am a gay American,” made him a lightning rod in the gay community. There were intensely divided opinions and camps; those who admired and praised the ex-governor for coming out so unambiguously, with his wife standing unflinchingly by his side, and others who dismissed him as a Machiavellian hack who callously stood against gay marriage for political expediency and to protect his cover. The polemics continue, with his detractors arguing that the lure of a generous advance is the true reason behind “The Confession.” “The Gay Governor Has No Clothes” Andy Humm declared in this newspaper.

In his book, McGreevey details the grueling balancing act of his double life—played out publicly as a married politician with children (“the lights of my life”) and a sexually active, self-loathing gay man functioning precariously on the down-low. The author’s situation represents one in ten married men who strive to compartmentalize their domestic and extracurricular sex lives. He relates the how as the son of working class Irish-American Catholic parents, he played by all the rules to be the “best little boy in the world,” striving diligently to achieve success; he attends Columbia University, receives a law degree in Georgetown University, and a master’s degree in education in Harvard. But, unfortunately, there were no degrees handed out for emotional intelligence; he sticks to straight society’s playbook, and makes a Faustian pact with himself. He stubbornly attempts to sublimate his erotic urges for men, flirts with girls, and studies Playboy centerfolds.

“When I made it my goal to rid myself of the desire, I was disavowing something else—my authentic self, my humanity… I know how it happens that a man like Roy Cohn… builds a sex life around male prostitutes—or an entertainer like George Michael who is one day dragged out of a public toilet,” McGreevey writes. During futile exercises of mind-over-matter, he even trolls for female “dates” on the Jersey shore, frequenting unsavory strip clubs with a straight friend.

“A great deal of New Jersey political culture is conducted by men folding bills into waistbands of women dancing in their laps at clubs with names like VIP and Cheeques,” the reader is told.

There is the ambitious, public McGreevey, negotiating the spiky ethical reefs of the New Jersey political culture; posing for photographs with his wife, Dina, while dandling his “precious” infant daughter, Jacqueline, as a proud father. There is also his furtive doppelganger, compulsively cruising back alleys and highway rest stops for anonymous sex. “How do you live with such shame?” he posits. “How do you accommodate your revulsion with whom you have become? You do it by splitting in two. You rescue part of yourself, the half that stands for tradition and values and America, the part that looks like the family you come from, the part that is acceptable and true. And you walk away from the other half the way you would abandon something spoiled. You take less and less responsibility for the abandoned half, until it seems to take on a life of its own—to become something you merely observe…”

“I used to make long lists of guys I had crushes on, scribbling their names like a teen-ager,” he confesses. The author handily dissects the illogical logic of straddling two identities by referring to John Knowles’ iconic coming-of-age novel, “A Separate Peace,” about the platonic relationship between two prep school students—one a charismatic athlete, the other, a hero-worshipping, sensitive loner—that gradually intensifies into a quasi-erotic co-dependency and moral dilemma. “Years later I realized I’d become both Gene and Phineas from ‘A Separate Peace’—the soul and the body, the person who tumbled from the tree and the person who made him fall.”

Dedicated to his parents and daughters, “who taught me unconditional love,” the memoir opens with an apt philosophic quote from Seneca’s “On the Shortness of Life,” and is a far more substantial read than Mary Cheney’s vacuous vanity production, the reprehensible “”Now It’s My Turn,” which the reading public—gay and straight—summarily ignored.

McGreevey discussed “The Confession” recently in an interview with Gay City News.

Jim McGreevey: I spoke with Paul [Schindler] recently when I was at the New School with The New York Times seminar. We had a very constructive conversation.

Michael Ehrhardt: I’ll try not to repeat any of the questions you’ve already fielded in other interviews. I suppose you managed to live as a married politician in what psychologists call a state of dissociation, or do you consider yourself to be bi-sexual?

JMcG: No. I am completely homosexual—and always was that way. But I couldn’t accept that, because I was taught that it was something wrong, and sinful. Part of the deconstruction of my former viewpoint involves confronting that fact.

ME: If it weren’t for the extortion case, would you have ever come out?

JMcG: Honestly, no. I wasn’t capable of it doing it voluntarily.

ME: In your book, you mention that your religion has been a great source of strength; that you try to be “Christ-centered.” Do you feel that’s paradoxical, since some critics would call that “cafeteria Catholicism?”

JMcG: I have friends in the Church who’ve welcomed me with unconditional love—in the true Christian sense. When I was at Catholic university, I felt limited by the intractable tenants of the church teachings. I’ve since learned to embrace the core of Christ’s teachings without the corrosive shame I used to feel. Sometimes, I spend time with Mark at Holy Cross, which is run by brothers of the Order of St. Benedict; it’s a very gay-friendly, sacred, and all embracing place.

ME: When you declared to the media, “I am a gay American,” gays took sides for or against you. Were you immediately aware of that?

JMcG: Certainly. And I can understand both sides. I would not have been that courageous if the necessity of the scandal hadn’t compelled me to make that declaration. I was an anti-hero for a lot of people. I worked over-time to do damage control. It was hellish trying to stave off the guy. It was the only thing to do. I had no other option; it was a matter of necessity. You can’t put a governorship on autopilot. Hopefully, I’ll be in the last generation of gay men who have to deal with the issues and trauma of coming out to society.

ME: Without being specific, are you privy to cases of other closeted office holders, and or prominent personalities.

JMcG: Yes, certainly. And I hope they can find a way to deal with it. Everyone must make that journey on their own, in their own way.

ME: Of course, your appointment of Golan Cipel to oversee the Port Authority, and Homeland Security is considered far more egregious than the extra-marital affair.

JMcG: I agree that it was very wrong. I bent all the rules to accommodate him, and I’m sorry for him.

ME: Does Golan still remain incommunicado?

JMcG: Oh, yes.

ME: You mention your hiring a detective, or researcher” in an attempt to locate his telephone number. Why?

JMcG: That’s after I finished my stay at The Meadows clinic.

ME: So he’s basically living incognito in Israel?

JMcG: Yes, he is.

ME: Is he in denial about his sexuality?

JMcG: Most likely. He was terrified about anything about his private life being exposed. As I say in the book, I attempted contacting him to apologize to him. It’s part of the 12-step program towards reparation and self-realization, and all the challenges that entails. I wanted to contact him to see that he was all right, and to let him know that I wished him no harm. But I haven’t spoken with him yet.

ME: In his lawsuit, Cipel accused you of sexually harassing him. Was the lovemaking you describe between yourself and Golan reciprocal? Or was he just faking it?

JMcG: No, it was genuinely mutual.

ME: So for all practical, or impractical purposes, you’re convinced he’s gay? You say being known as gay would have been worse than death for him.

JMcG: Definitely. He’s denied having a homosexual identity, but I don’t believe that.

ME: He was a former member of the Israeli navy. Military service is compulsory there, but they don’t ostracize gays in the military.

JMcG: Not like the ridiculous Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the U.S. It’s policies like that that perpetuate the culture of shame, and coerce people to remain in the closet. The very policy fosters deception. Shame is so corrosive.

ME: How do you keep busy these days, apart from promoting your book?

JMcG: I spend a good deal of time traveling to universities. I’m presently going to the University of Michigan

ME: You tell of negotiating the “slippery slope” of New Jersey politics—back room deals, favor swapping, nepotism, character assassination, wire-tapping, etc. It sounds like a real cesspool.

JMcG: No more so than what’s happening right now in Washington D.C.

ME: Do you fear any retaliation for revealing that aspect of New Jersey government?

JMcG: Not really. It’s unfortunate that the political system of public service is of such a ludicrous nature, a vicious syndrome, involving money, power, and ego. Everything is geared to cover-up the shady deals, to cynically shape public opinion, and appeal the lowest common denominator. Those are the rules of the game, and power and money become the entire point.

ME: How is your partner Mark coping with the media circus?

JMcG: Very well. He’s incredibly patient.

ME: Your wife, Dina, was very courageous to stand by your side. Will she remain out of the public eye?

JMcG: Yes. She is still going through the healing process, and she needs the time for herself. I wish her all the best in the future. She’s attractive and young, and she deserves a loving and fulfilling life.

gaycitynews.com