As darkness descended on the New York City AIDS Memorial in the West Village on December 1, 10 activists who, in the words of one, have long been “thriving” with HIV paid tribute to an equal number of writers, poets, and novelists who fell to the first of the pandemics we encountered in our lives.

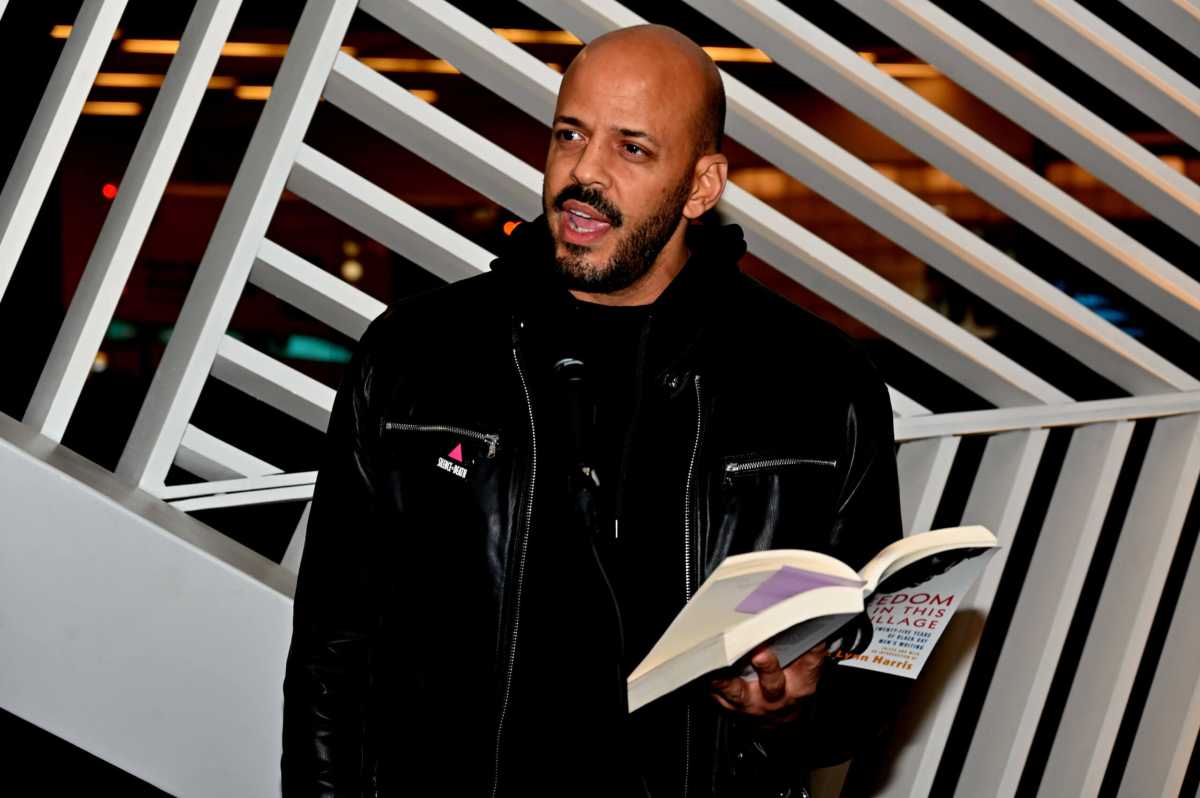

In the hour prior to the 30th annual “Out of the Darkness Candlelight Vigil” marking World AIDS Day, the 10 — in a program of readings curated by novelist, journalist, and teacher Tim Murphy — restored to life the words of 10 remarkable artists whose work highlighted themes of activism and community, of humor, of the ecstatic joys of sex, and of love.

Kevin Hertzog recalled the credo that his good friend Michael Slocum, who died in 1995, co-wrote (with Jim Lewis) for the HIV support group Body Positive. “You Are Not Alone,” reprinted in every issue of the group’s magazine, aimed to honor emotions such as fear and anger felt by people living with HIV, while challenging the shame and guilt initially felt by many who were newly diagnosed. The credo also underscored the urgent need to seek support from others facing the same health challenges.

“What you are feeling now is perfectly normal. Anger, fear, confusion, numbness, depression — all are completely natural reactions to the kind of news you’ve heard,” the piece read, while reminding positive folks, “You have to keep in mind that there are many people who are HIV-positive who are living productive, happy lives, and you can be among them if you choose.”

It went on to say, “You are facing enough right now; you don’t need to punish yourself for testing HIV-positive also… You are not ‘damaged goods.’ You are still a valuable person, as capable of giving and receiving love as ever.”

The credo concluded with a reminder: “Those millions of people living successfully with HIV are people who’ve reached out to get the help they needed.”

Ivy Kwan Arce read from poet, writer, and editor B.Michael Hunter’s praise for his fellow activist Keith Cylar, co-founder of Housing Works, whose death in 2004 would come three years after Hunter’s.

In “Doors Will Open!,” Hunter wrote, “Keith/ Like a black panther,/ A militant vanguard in the fight/ Could no longer/ sit, watching/ Lives needlessly lost.”

Mary Bowman, who was born with HIV and died at age 30 in 2019, was recalled by Kineen MaFa, who read from the poem “I Know What HIV Looks Like.”

“It was predicted that she would breathe her last breath before 5/ But now/ Here she stands 5 foot 9 / 15 years after her expected demise / Flashing a smile that blinds eyes trying to see her pain,” Bowman wrote in 2014.

Later, the poem continues, “She can’t allow people to go on and think/ That HIV only looks like/ Skinny bodies, pale skin, open sores, and baby thin hair/ She can’t help but start a movement that does more than just wear red t-shirts on December 1st / No matter how much it hurts… Knowing what HIV looks like/ Comes with the price of my life nailed to a ruthless disease/ But I’d rather die telling people what HIV looks like than to live with knowing I haven’t said a word.”

Lillibeth Gonzalez read the self-epitaph that Cuban exile Reinaldo Arenas, author of the indelible memoir of life as an out gay man under Fidel Castro, “Before Night Falls,” wrote as he was giving up his fight against AIDS by taking his life in New York in 1990.

In his final written work, a poem, Arenas wrote, “He lived for life’s sake, which means seeing death/ as a daily occurrence on which we wager/ a splendid body or our entire lot… The everyday becomes hateful,/ there’s just one place to live — the impossible…. He wanted no ceremony, speech, mourning or cry,/ no sandy mound where his skeleton be laid to rest/ (not even after death did he wish to live in peace)./ He ordered that his ashes be scattered at sea/ where they would be in constant flow./ He hasn’t lost the habit of dreaming:/ he hopes some adolescent will plunge into his waters.”

While some of the writers honored on World AIDS Day spoke passionately about activism and struggle, others used humor as a weapon to pierce the widespread complacency that the pandemic occasioned.

In the epilogue to his second novel “Spontaneous Combustion,” David Feinberg, who died in 1994, imagined a fantasy scene in 1996 when AIDS would be cured. Amidst “ribald” celebrations in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York, anti-gay figures — from comedian Andrew Dice Clay to New York Cardinal John J. O’Connor — would still be “at large.” Gay men, grateful for the support their lesbian sisters had lent during the health crisis, would oversee daycare at women’s music festivals and give them “their favorite dresses,” as read by Bruce Ward.

Iris de la Cruz, who organized support groups for positive folks from communities even more marginalized than gay men and for whom Iris House is named, wrote how HIV had suddenly become a “very chic disease.” In “Kool Aid With Ice,” read by Patricia Shelton, de la Cruz, who died in 1991, wrote that phony positives could be sniffed out since they did not wear beepers that went off every four hours to remind them to take their meds.

“I had a good time getting this disease,” she wrote, “and I’m going to have a good time dealing with it. Although maybe not in the same way.”

Poet Essex Hemphill, famed for his exploration and celebration of Black gay sexuality, was remembered by Jay W. Walker, who read “Vital Signs,” the last published writing of Hemphill’s, who died in 1995.

Describing the after-dark scene along the Schuylkill River near the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Hemphill wrote, “A flock of queens/ gather on the corner./ A line of cars/ snake around the block./ The bejeweled/ exotic birds/ preening/ and trilling/ on the corner/ are in danger./ Even those/ with talons.”

Later in the poem, referring to a man with a lover, Hemphill wrote, “You are lucky./ You are not like/ so many of our generation/ hungering for love,/ begging to be worked./ I offer you/ the only leverage/ I possess:/ a strong/ stern tool./ Take it!/ Use it/ for anything/ but raping,/ anything/ but killing.”

Borrowing the title of an iconic song from French chanteuse Edith Piaf, David Frechette, who died in 1991, dismissed the notion that his HIV infection caused him to regret his sexuality.

In “Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien,” read by John Grauwiler, Frechette wrote of “minions… “brandishing crosses, clutching Bibles” as they “circle round my sick room” imploring him to “renounce your sins.”

“‘Don’t you wish you’d chosen a normal lifestyle?’/ ‘Sister, for me, I’m sure I did,’” Frechette wrote.

The poem continued, “I don’t regret late night and early a.m./ Encounters with world-class insatiables./ My only regrets are being ill/ Bed-ridden and having no boyfriend/ To pray over me. / Engrave on my tombstone:/ ‘Here sleeps a happy Black faggot/ Who lived to love and died/ With no guilt.’”

Several of the writers honored on Wednesday evening spoke movingly about love itself, even when burdened with insurmountable grief.

In “Us,” the poet Tory Dent, who died in 2005, wrote, “in your arms/ it was incredibly often/ enough to be/ in your arms/ careful as we had to be at times/ about the I.V. catheter/ in my hand,/ or my wrist,/ or my forearm/ which we placed, consciously,/ like a Gamboni vase,/ the center of attention…”

Read by curator Murphy, the poem ended, “you don’t need reasons to live/ one reason, blinking in the fog,/ organically sweet in muddy dark/ incredibly often enough/ it is, it was/ in your arms.”

In “No Goodbyes,” writer and poet Paul Monette, who died in 1995, wrote achingly of his final hours with lover Roger Horwitz.

The poem, read by Ed Barron, began, “for hours at the end I kissed your temple stroked/ your hair and sniffed it it smelled so clean we’d/ washed it Saturday night when the fever broke/ as if there was always the perfect thing to do…”

At 4 a.m. on Horwitz’s last day, he “took the turn” and Monette cried, “WAIT WAIT I AM THE SENTRY HERE,” and then concluded, “my darling one last graze in the meadow/ of you and please let your final dream be/ a man not quite your size losing the whole/ world but still here combing combing/ singing your secret names till the night’s gone.”