It’s the dead of winter, and I’m reminded once again of all the indoor treasures New York has to offer. For my taste, museums rank near the top. They are full of amazing displays and fascinating artifacts, as well as great places to eat, meet, or just sit and take it all in. Plus, as a recently published study shows, by going to the museum at least once a year you give yourself a better chance of living longer.

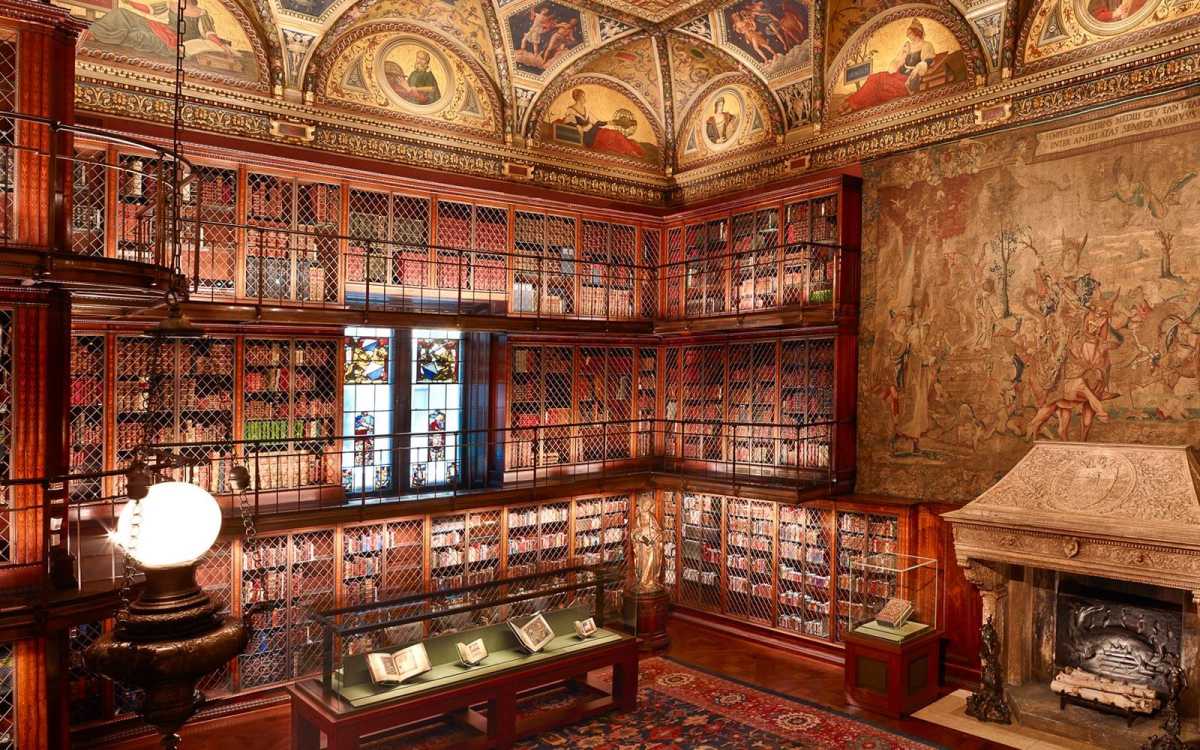

This past week, I had the chance to have a wonderful private tour of the Morgan Library & Museum, located on Madison Avenue at East 36th Street. The former home and library of financier J. P. Morgan, it features stunning interiors and its special exhibitions and permanent collection showcase books, drawings, manuscripts, paintings, photographs, prints, and more from around the world, dating back to the fifth century BCE.

During the tour, I stood with museum director Colin B. Bailey and Philip Palmer, curator and head of the Department of Literary and Historical Manuscripts, before a beautifully laid out selection of books and manuscripts. We all leaned in to examine the first item. It read:

A black day to begin a blue journal. “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” in rehearsal. The leading actress (Bel Geddes) inadequate, the play not coming to life enough. I’m tired and a bit drunk and I have a beastly cold — I am already making plans for a far away flight (perhaps as far as Ceylon) the night the play opens in New York!

Most New Yorkers can relate to this experience of job stress compounded by a bout of the winter sniffles. But these were the thoughts of the celebrated playwright Tennessee Williams, penciled in a cursive script in his journal on February 22, 1955. The notebook, which is catalogued by the very Tennessean title, “A Drunkard’s Poem to a Lover,” contains entries from 1955 to ’58 that range in tone from the titillating to the tortured. That worrisome production he says is stressing him out? It won the Pulitzer Prize and received four Tony nominations, including Best Actress for the “inadequate” Barbara Bel Geddes, a native New Yorker who two decades later beamed into American living rooms weekly as Miss Ellie, the steely-eyed matriarch on the long running nighttime soap opera “Dallas.”

We proceeded, time traveling from one object to the next. Thinking about the hands that created or touched these artifacts made their respective moments in history simultaneously immediate and unfathomable.

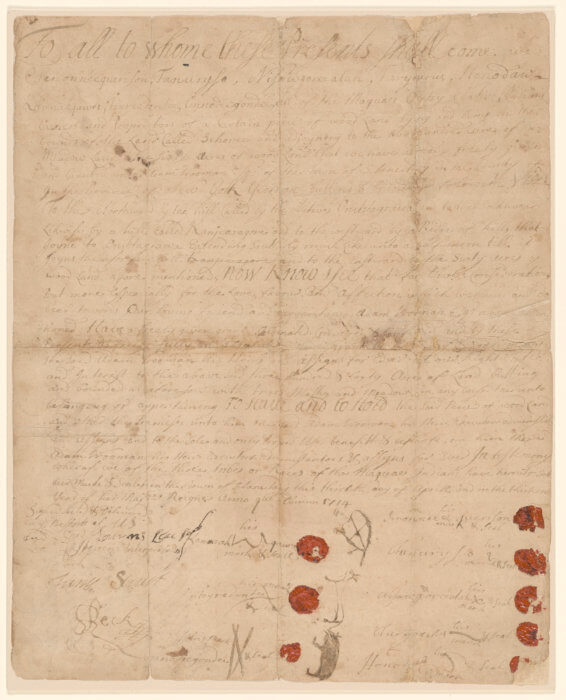

“Manuscripts fascinate me because of their dual identity as both unique artifacts and everyday objects,” Palmer said. “They bear the aura of famous writers or historical events, but also emerge from daily acts of written communication such as diary entries, rough notes, financial records, and legal documents.”

It was chilling to inspect a deed from 1714 that transferred 340 acres of land near present-day Schoharie, New York, from eight signatories of the Mohawk Nation to one Adam Vrooman, a Dutch settler residing in Schenectady. The document represents the first step in transforming that region from complete Native territory prior to the 18th century to an area less than one percent Native American, according to the most recent US census.

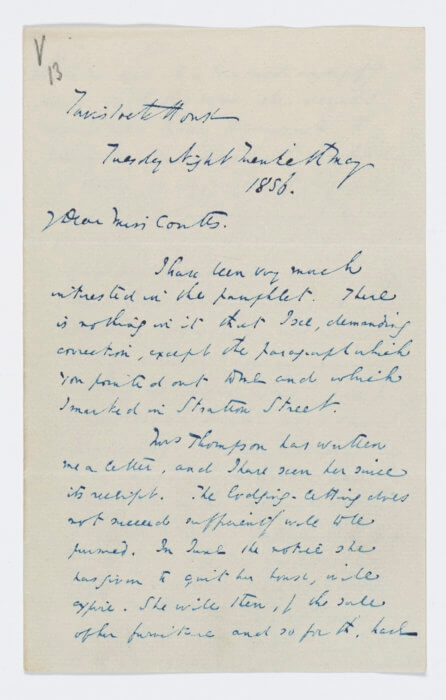

We moved on to a letter composed in 1856 by Charles Dickens, author of “A Tale of Two Cities” and other classics of Victorian literature you probably CliffsNoted back in middle school. This particular correspondence is especially remarkable because it exposes a different side of Dickens, his work, still couched in the logic of Victorian moralism, as co-founder of Urania Cottage, a home for women sex workers. The letter is written in support of a woman endeavoring to restart her life with her children as emigrants to Canada.

With public health officials advising citizens all over the world about precautions for international travel in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak, it was intriguing to be shown a document dating back to 1787 that addressed this same sort of concern. According to the written attestation by Dr. Luiz Botelho da Sylva Valle, the Purveyor of Health to the Court and Kingdom of Portugal, the city of Lisbon was proclaimed “free from plague or any other contagion.” The document was presented as a passport to one Jean Mazeret, himself a doctor, authorizing the holder to sail for France germ-free.

I viewed a letter by author James Baldwin to one Richard Clarence, penned in 1968 in Hollywood, where Baldwin was working on a screenplay about the life of fallen civil rights leaders Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Medgar Evers. In it, Baldwin is breaking down what he means by “sexual authority,” a theme in his gay romantic novel, “Giovanni’s Room.” Next, we inspected an original bound screenplay and accompanying director’s notebook of the 1987 film “Maurice,” a gay love story of a much earlier time, based on the novel of the same name published in 1971, one year after the death of its author, E.M. Forster.

The legendary director of “Maurice,” James Ivory, now 91 years old, gifted the materials from the film in 2018 on the heels of becoming the oldest Oscar winner, for Best Adapted Screenplay of the coming-of-age novel, “Call Me by Your Name.”

“Though the bulk of the James Ivory Archive is now at the University of Oregon, Mr. Ivory wished for a portion of his collection to stay in New York City,” Palmer said.

The Morgan displays items from its permanent collection in an ongoing exhibition, “Treasures from the Vault,” which changes every four months. The current rotation, on view until February 23, features manuscripts and objects whose provenances span a 700-year period. Among others is an original copy of Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” from 1885, a letter from “Pride and Prejudice” author Jane Austen (1775-1817) to her sister, and a pop-up fairytale book created by the contemporary artist Kara Walker entitled “Freedom,” about racial and sexual violence in the life of an emancipated female slave. A companion exhibition, “Speak, Act, Vote, Resist: Citizen Voices from The Gilder Lehrman Collection,” features artifacts spanning the history of social justice mobilization in the US, from abolition to suffrage to civil rights to Stonewall.

The Morgan has no shortage of holdings of LGBTQ literary or historical interest. For instance, in 2013, it acquired the collection of the photographer Peter Hujar, comprising some 100 photographs, plus contact sheets and assorted memorabilia, chronicling “the public unfolding of gay life in the 1970s,” the economic decline of New York City, and the artist’s own biography (he died of AIDS in 1987 at age 53).

On permanent display is a terra-cotta bust by the artist Jo Davidson of the Morgan’s first librarian and director, Belle da Costa Greene (1879–1950). Greene was a light-skinned African American woman who passed for white throughout her career in order to get the chance to contribute her considerable expertise to an institution that would otherwise have barred her.

“I want our visitors to be introduced to figures and movements both familiar and unfamiliar, historical and contemporary,” said Bailey. “I want them to be inspired by these precious physical traces of the great achievements in the Western tradition, from medieval to modern times. We are a place where hearts and minds can take wing and soar.”

THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM | 225 Madison Ave. at E. 36th St. | Tue.-Thu., 10:30 a.m.-5 p.m.; Fri., 10:30 a.m.-9 p.m.; Sat., 10 a.m.-6 p.m.; Sun., 11 a.m.-6 p.m. | $22; $14 for 65 and over; $13 for students; free on Fri., 7-9 p.m. | themorgan.org