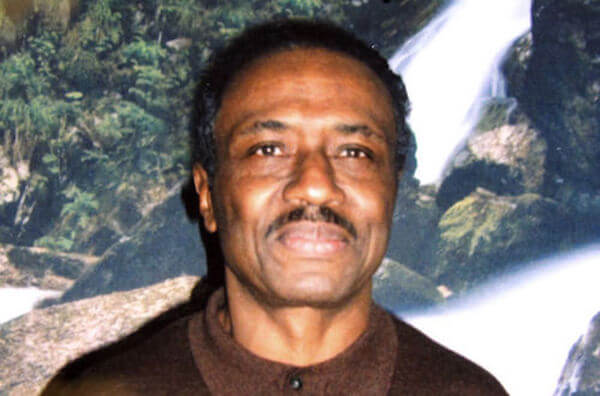

Herman Bell in 2013. | SUSIE DAY

Only a couple of years ago, the New York State Parole Board was a draconian gimmick to keep people in prison — regardless of how they had grown and changed over their years inside — until they died of systemic abuse or neglect or, if they lived long enough, old age. This was especially true for people convicted of killing police officers: “offenders” who could expect never to leave prison alive, because of the unchanging “nature of the original offense.”

John MacKenzie, for instance, accepted responsibility and expressed deep remorse for his shooting of Officer Matthew Giglio in 1975. He spent more than 40 years in New York prisons, during which he mentored other prisoners, advocated for victims’ rights, became a Zen Buddhist, and maintained a perfect disciplinary record. In August 2016, at the age of 70, MacKenzie killed himself after being denied parole for the 10th time. In his last letter, he wrote his daughter about his latest denial, quoting a Buddhist text: “Can a new wrong expiate old wrongs?”

MacKenzie is only one reason among hundreds why the Parole Board has begun its own process of rehabilitation. In recent years, tireless organizers (one of whom, full disclosure, is my esteemed partner, Laura Whitehorn) have worked to push the Board to focus on “risk and need assessments” in considering suitability for parole, including factors beyond the original crime such as what someone’s done inside, their family, job, and community awaiting them outside, and especially their risk to public safety. The Board expanded and humanized parole regulations, requiring commissioners to give factual, individualized reasons for their parole decisions. In 2017, the State Senate approved the hiring of six new parole commissioners.

PERSPECTIVE: Snide Lines

On March 13, the State Parole Board did something amazing — and eminently reasonable. Using its new, progressive regulations, a panel of three commissioners approved the parole of my friend, Herman Bell, on his eighth try.

Herman, whom I’ve visited for years, is someone the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association and tabloids reflexively call “vermin,” a “cold-blooded cop killer,” and “monster.” But I, being part of the queer community, and having long internalized being seen as a “monster,” know first-hand that most monsters are not what they’re cracked up to be.

Until only few weeks ago, I, a pinko dyke and card-carrying cynic, fully expected to keep visiting Herman until he died in prison. After all, Herman’s been behind bars more than 45 years because, in 1975, he, along with two other men, was convicted of the fatal 1971 shooting of Officers Waverly Jones and Joseph Piagentini in Harlem.

Herman is now 70 years old. Over his years inside, he’s come to express deep sorrow for his actions. He’s never stopped learning, garnering three college degrees; he’s never stopped trying, in small acts of human kindness and larger acts of counseling young men and organizing outside community projects, to make the world better. And, given the Parole Board’s current “risk and need assessment” scale, Herman scores the lowest possible risk to public safety, or “recidivism.” Herman’s not perfect, but he is one of the strongest, gentlest people I know.

Herman’s original release date was April 17. But he’s still in prison. A couple of weeks ago, he sent out a package of clothes he expects to wear when he gets out. He’s all packed and ready to go — but can he?

Beginning March 13, the day Herman’s parole was announced, through the rest of March and into April, the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association launched a series of attacks, demanding a suspension of Herman’s release, saying the Board broke the law in failing to consider the 1975 judge’s sentencing minutes and the impact statements from the victims’ families. The Parole Board duly reviewed this evidence and reaffirmed its decision to release Herman. Herman was good to go.

Until April 4, when Officer Piagentini’s widow, in tandem with the PBA, sought and received a temporary restraining order to suspend Herman’s release, pending an April 13hearing in Albany, before Judge Richard M. Koweek. One week later, Koweek ruled that Mrs. Piagentini and the PBA had no legal standing and that “[e]ven if the court was to consider the Parole Board’s decision on its merits, it would still rule against the Petitioner.” The PBA says it will appeal. And the judge also stayed Herman’s release until 5 p.m. Friday, April 27.

Meanwhile, back at the Legislature, the New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic, and Asian Legislative Caucus — 53 state lawmakers representing a quarter of New York State residents — released a statement supporting the Board’s decision for Herman’s parole. This historic action was predictably ignored by mainstream media, which instead zeroed in on cop-killer-condemning PBA press conferences, outraged editorials, and the NYPD police commissioner’s revulsion at the release of Herman, a man he’s never met.

But thinking beyond Herman, this case could be a watershed. If Herman Bell can be seen by the New York State Parole Board as a dimensional human being; if he can be allowed out of prison on the strength of sound, humane reasoning, so can — so should — thousands of other human beings aging inside prison. People convicted of violent crimes who have transformed their lives and deserve to spend their last years living among the rest of us.

Writing about Herman’s parole is hard. The killing of police officers is as wrong as the killing of anyone else, including the scores of unarmed people of color, shot down by cops who almost never face trial. There is grief on every side. But rather than being a springboard for vengeance, grief, says the poet Rumi, can also be a springboard for compassion: “If you keep your heart open through everything, your pain can become your greatest ally in your life’s search for love and wisdom.”

As I sit here, typing, it remains to be seen what, if anything, the PBA may attempt to prevent Herman’s release. Which may — or may not — happen after 5 p.m. this Friday. I’m keeping my cynical, pinko dyke heart open…

Susie Day is the author of “Snidelines: Talking Trash to Power,” published by Abingdon Square Publishing.