A Black gay historian is re-examining the 1982 raid of an LGBTQ bar in midtown in a new film called “Gay, Black, and Blue: The Raid on Blues Bar.”

Beau Lancaster, a City University of New York adjunct professor of history, is the filmmaker behind the unfinished documentary about a violent police raid at an LGBTQ bar in Times Square that primarily served Black gay men and some transgender women.

It was around 10:30 p.m. on September 29, 1982 when 20 NYPD officers raided the bar. During the nearly 30-minute raid, the police officers shouted homophobic slurs at the estimated 40 patrons and smashed up the bar.

Lancaster learned of the raid while working on his graduate school capstone project in 2021. He was searching for a historical event that intersected three key aspects of his identity.

“I was really trying to find something that could tell all those living stories: a native New Yorker, Black, [and] queer,” Lancaster said. “And really trying to find what that history looks like.”

Blues Bar fit the bill. He’s now turning it into a feature-length documentary.

Stonewall for Black gay Americans

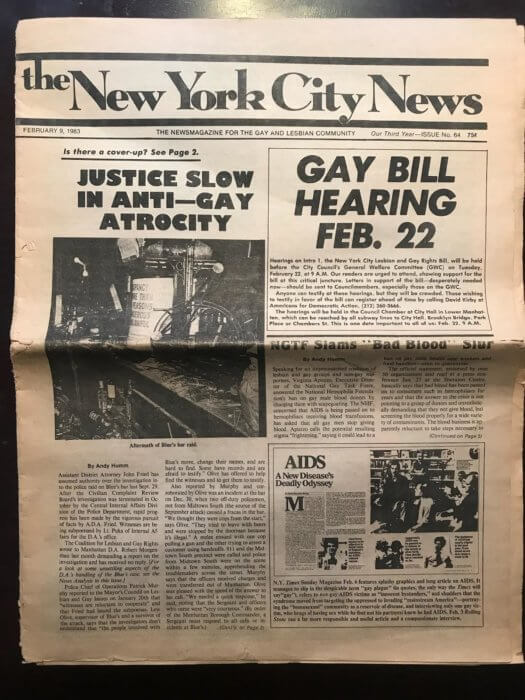

“It was sort of like a second Stonewall,” said veteran gay journalist Andy Humm, a Gay City News contributor. Humm covered the Blues Bar raid for The New York City News, an LGBTQ newspaper at the time, for a year and a half from the raid to the close of the case.

WomaNews, a feminist newspaper, and The Village Voice also covered the Blues Bar raid and the protests. Sarah Schulman and Peg Byron were with WomaNews and the late Arthur Bell, a gay reporter, was with The Village Voice.

James Credle, a former assistant dean of students at Rutgers University who was a member of the anti-racist gay group Black and White Men Together, said in the film that the bar’s legacy must live on.

“It will never be Stonewall, but it could be a Stonewall for Black Americans,” Credle said.

The 1982 Blues Bar riots haven’t carried the same reverence in LGBTQ history as the 1969 Stonewall Riots. The Stonewall Riots lasted through six nights of protests that followed the June 28 police raid of the Stonewall Inn, a mob-run bar frequented by the LGBTQ community.

Blues Bar and the raid

NYPD officers claimed that some patrons attacked two police officers nearby and accused the bar of being involved in criminal activity. Witnesses at the time denied the police’s claims and accused police officers of harassing patrons at the bar.

According to Schulman and Humm, none of the bar’s patrons were ever arrested or charged. The investigation by then-Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau’s office never went anywhere. The police officers’ evidence against Blues Bar was never substantiated. The officers were never disciplined.

Schulman and Humm appear in the film, where they discuss the Blues Bar raid and what was happening in gay New York in 1982. Also interviewed in the documentary are Credle and Dr. Joyce Hunter, who was among the 1,500 demonstrators angered by the raid of Blues Bar that flooded Times Square October 15, 1982.

The New York Times did not cover the raid despite its offices being across the street from the bar. It only dedicated 125 words to the demonstration, which occurred weeks after the raid.

Mikell Greene Grand, an African-American gay man, frequented Blues bar regularly in the early 1980s when he was in his early 20s. He described it as a golden age of gay nightlife in New York City, where he had a bar he went to every day of the week. On Mondays, he would go to Blues Bar, which he recalled as a small dive bar that was frequented by a clientele that was 99% Black and gay men. Blues was a place to get cheap drinks and have a good time with DJ Candy Stevens mixing the music, he said.

NYPD officers came into the bar often. An announcement would be made as they were entering the bar. The music would be turned down, patrons would act casual, the officers would look around and leave, the music would turn up again, and the party would continue.

“It was just part of the culture,” Greene Grand said. “We just kind of adhered to the rules and regulations and you just hoped that you got home safely that night without a problem.”

Greene Grand wasn’t at Blues bar the night of the raid. At the time, he was part of a culture that “passed” as straight and had a comfortable job, he said. They didn’t hit the streets shouting for their rights. They preferred not to make a scene.

Racism and gentrification

The raid happened against the backdrop of the LGBTQ movement, the emerging HIV/AIDS crisis, and racism and segregation within the LGBTQ community. At the time, many LGBTQ people of color were “double carded” or were required to present two forms of identification to enter mostly white gay bars.

The fact that the Human Rights Campaign’s first black-tie fundraiser was only a few blocks away from Blues Bar at the Waldorf Astoria at the time of the raid did not escape activists’ and reporters’ attention.

In a Washington Post op-ed, Lancaster quoted Lionel Mitchell’s coverage of the Blues Bar raid in the the New York Amsterdam News.

“Many white gays were asserting that the police would not have dared brutalize white people in the same way,” Lancaster quoted Mitchell.

“The poorly organized Blacks, scarcely protected by the all-new won ‘gay rights,’ were being stomped within an inch of their lives by that police department,” Mitchell wrote at the time.

“That illusion of protection was not available for Black queer people,” Lancaster told Gay City News.

It was suspected that the raid was driven by the gentrification of Times Square as well as the presence of off-duty police officers working security for the New York Times. The suspicions were never proven, Schulman said.

Distrust of New York’s government officials, from Mayor Ed Koch’s office to the police, compounded the situation, added Humm, who stated that many victims would not speak to investigators.

No NYPD officers or anyone from the New York Times from the era were interviewed for the rough cut of the film that Gay City News viewed.

Then and now

Lancaster was shocked by the dynamics between race, the LGBTQ community, and what it meant to be queer at the time and how that affected his life as a gay, Black, New Yorker in the 21st century.

“For me to find firsthand, the account of Black queer men who were alive during that time period was very, very difficult,” Lancaster said.

Schulman noted in the film that many Black gay writers of that generation were lost to AIDS.

“What would this community have looked like in relation to possibly mentoring me?” Lancaster asked. “I think that’s one of the most saddest and morbid pieces in relation to this film.”

Lancaster wants the documentary’s audiences to see the patterns and the creation of conditions and how they relate and play out in different ways today.

“History is not remembering dates; it’s remembering patterns and identifying the patterns and the similarity between us and articulating arguments,” Lancaster said.

Lancaster estimates it will take about $15,000 to complete the film. He’s launching a Kickstarter campaign soon to complete the post-production phase of the documentary. For more information, contact Lancaster on Instagram and Twitter at @theshadyhist101.