Capping litigation that began in 2015, a three-judge panel of the Richmond-based Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in a 2-1 vote on August 26 that the school board in Gloucester County, Virginia, violated the statutory and constitutional rights of Gavin Grimm, a transgender boy, when it denied him the use of boys’ bathrooms at the high school there.

This may sound like old news, especially since other federal appellate courts, most notably the Philadelphia-based Third Circuit, the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit, the San Francisco-based Ninth Circuit, and the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit, have either ruled in favor of transgender students’ rights or rejected arguments made by cisgender students and their parents against such equal access policies.

But Grimm’s victory is particularly delicious because the Trump administration intervened at a key point in the litigation to reverse the support the Obama administration had earlier given Grimm’s lawsuit.

Grimm, identified as female at birth, claimed his male gender identity by the end of his freshman year, taking on the name Gavin and dressing and grooming as male. Before his sophomore year, he and his mother came to agreement with the high school principal about his using the boys’ bathrooms, which he did for several weeks without incident. As word of this spread, however, some parents deluged the school board with protests, leading to two stormy public meetings and a vote that trans students in the district — meaning, at that moment, Grimm alone — were restricted to using a single-occupant bathroom in the nurse’s office or bathrooms consistent with their “biological sex” as identified at birth.

Represented by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Grimm filed suit seeking a court order to allow him to resume using the boys’ bathrooms, and the Obama administration weighed in with a letter to the court siding with Grimm’s argument that the school board’s policy violated Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which bans sex discrimination against students. Despite that letter, the district judge granted the school board’s motion to dismiss the Title IX claim, reserving judgment on Grimm’s alternative claim under the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.

Grimm appealed that dismissal, and a three-judge panel of the Fourth Circuit ruled that the district court should have deferred to the Obama administration’s Title IX interpretation.

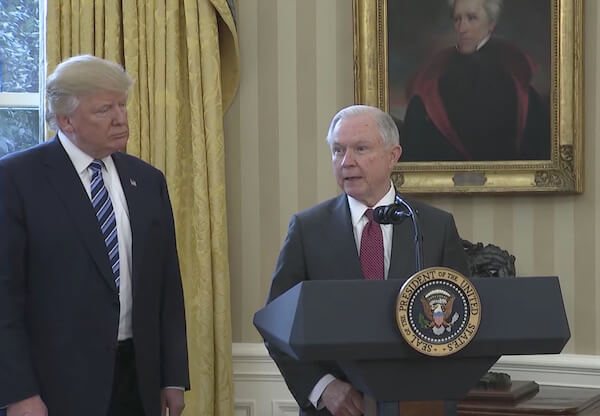

The school board, in turn, sought review from the US Supreme Court, which scheduled the case for argument in March 2017. But those arguments never took place, because the new Trump administration, at the behest of Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, formally withdrew the Obama interpretation on Title IX. Since the Fourth Circuit’s reasoning was based on deference to the Obama administration’s posture, the Supreme Court canceled arguments on the school board’s appeal of the Fourth Circuit ruling and sent the case back to the district court. (Later in 2017, Sessions would send all Executive Branch agencies a memorandum disputing the Obama administration’s interpretation that discrimination based on gender identity was necessarily prohibited sex discrimination; in June of this year, on the matter of employment discrimination, the Supreme Court rejected Sessions’ view and embraced Obama’s.)

By the time the case got back to the district court in the spring of 2017, Grimm had graduated and Gloucester County moved to dismiss the case as moot. Grimm insisted that the case continue since he should be entitled to damages for the discrimination he suffered and he would like the freedom to use the male facilities if he returned to the school as an alumnus. Later, he also requested that the school issue him an appropriate transcript in his male name identifying him as male, since he was stuck in the odd situation of being a boy with a high school transcript identifying him as a girl.

Ultimately, the district court ruled in Grimm’s favor on both his statutory and constitutional claims, but the school board was not willing to settle the case, again appealing to the Fourth Circuit. The August 26 ruling is the result.

The case was argued in the Fourth Circuit before a panel of two Obama appointees, Judges Henry Floyd and James A. Wynn, Jr., and an elderly George H.W. Bush appointee, Judge Paul Niemeyer (who had dissented from the original Fourth Circuit ruling in this case). In light of the rulings by other courts of appeals on transgender student cases and the Supreme Court’s decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, on June 15 of this year, holding that discrimination because of transgender status is discrimination “because of sex” under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, the result in this new ruling was foreordained.

Judge Floyd’s opinion for the panel, and Judge Wynn’s concurring opinion, both go deeply into the case’s factual and legal issues and articulate a sweeping endorsement of the right of transgender students to equal treatment in federally-funded schools guaranteed under Title IX. Public schools are also bound by the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, and the court’s ruling on the constitutional claim was just as sweeping.

The court first rejected the school board’s argument that the case was moot, since the damages available for a Title IX violation did not depend on Grimm still being a student. The district court had awarded him only nominal damages, but that was enough to keep the case a live controversy, as did the school’s continuing refusal to issue him a proper transcript, which the court also held was illegal.

Both Floyd and Wynn rejected the school board’s argument that there was no discrimination against Grimm because he was not “similarly situated” to cisgender boys — they firmly asserted that Grimm is a boy entitled to be treated as a boy, regardless of his sex as identified at birth.

Judge Niemeyer’s dissent rests on a Title IX regulation, which Grimm did not challenge, providing that schools could maintain separate single-sex facilities for male and female students, and his rejection of the idea that Grimm is male for purposes of this regulation. Niemeyer insisted that Title IX only prohibits discrimination because of “biological sex” — a term which the statute does not use. The school did all that the statute required, in Niemeyer’s view, when it authorized Grimm to use the private bathroom in the nurse’s office or the girls’ bathrooms.

The panel majority accepted Grimm’s argument that the school’s policy subjected him to discriminatory stigma — long recognized by federal courts as the basis for a constitutional equal protection claim — as well as imposing physical disadvantages. As a boy, he would not be welcome in the girls’ bathroom, and the nurse’s office was too far from the classrooms for a break between classes. As a result, he generally avoided using the bathroom at school, leading to awkward situations and urinary tract infections.

Floyd’s opinion did not rely on the Bostock ruling for its constitutional analysis, instead noting that many circuit courts of appeals have accepted the argument that government policies discriminating because of gender identity are subject to heightened scrutiny — and so are viewed as presumptively unconstitutional unless they substantially advance an important state interest. The majority did not think that excluding Grimm advanced an important state interest, especially after the school board altered the bathrooms to afford more privacy, an obvious solution to the privacy issues the board claimed to be addressing in barring him from the boys’ bathrooms.

Turning to the statutory claim, Floyd pointed out that judicial interpretation of Title IX has always been informed by the Supreme Court’s Title VII rulings on sex discrimination, so the Bostock decision carried heavy weight. The school board lacked a sufficient justification under Title IX to impose unequal access to school facilities on Grimm.

Gloucester County might do well to read the writing on the wall and concede defeat. Or it can petition the Fourth Circuit for en banc review by its full 15-judge bench or seek Supreme Court review a second time. The Fourth Circuit is one of the few remaining in the nation with a majority of Democratic appointees, so seeking en banc review, which requires that a majority of the active judges vote to review, would be a long shot.

On the other hand, Justice Neil Gorsuch’s decision for the Supreme Court in Bostock refrained from deciding — since it wasn’t an issue in that case — whether excluding transgender people from bathroom facilities violates sex discrimination laws, and this case would provide a vehicle for addressing that issue. It takes only four votes on the Supreme Court to grant review, so there may yet be another chapter in the saga of Grimm’s legal battle.

It is also possible that the St. Johns County School District in Florida, which lost in the 11th Circuit in a virtually identical ruling, might also seek Supreme Court review, so one way or another this issue may get on to the high court’s docket this term or next.

ACLU attorney Joshua Block has been representing Grimm throughout the struggle, but the case was argued in May by cooperating attorney David Patrick Corrigan from the Richmond firm of Harman Claytor Corrigan & Wellman. Virginia Attorney General Mark Herring was joined by other state attorneys general in siding with Grimm by submitting amicus briefs.