I was a precocious reader from my earliest age, devouring the written word as my chums gobbled candy. Unlike them, I found my heroes in books, not in the movies. But when, at the age of 10, I saw the 1957 black-and-white film “Fear Strikes Out,” I found myself fascinated — captivated, really — by Anthony Perkins when, in his first major critical success, he played the mentally troubled Boston Red Sox baseball player Jimmy Piersall striving unsuccessfully to please an emotionally distant, demanding, and authoritarian father, cuttingly portrayed by Karl Malden.

For reasons I was then too young to put into words, I was drawn to Perkins as a moth to a flame — to his awkward grace, his intelligent but soulful and troubled eyes and shy half-smile, his marvelously tall and athletic slim, wide-shouldered body, his vulnerability.

After that, I would immediately go see anything with Perkins in it. At 13, with my hormones beginning to rage (although my sense of difference from other boys still had not found a consciously acknowledged vocabulary), I rushed to see him in what I knew even then was a trashy romantic comedy, 1960’s “The Tall Story” — my interest being to see Perkins in a minimum of clothing as a college basketball star opposite his on-screen love interest, Jane Fonda.

I went so far as to acquire the three albums Perkins recorded as a quite talented pop crooner in the mid and late 1950s. With all sorts of moist, only half-formed fantasies swirling amorphously through my head, I wore out, with repeated playing, his 1958 chart-topping hit, “Moonlight Swim.” As with his pop music efforts, it’s often forgotten that Perkins was nominated for a Tony award for his role in the 1960 Frank Loesser musical “Greenwillow”.

It was not until a decade later, when I was caught up in the post-Stonewall gay liberation effervescence and able to begin accepting that my orientation was (that dreaded word) homosexual that I finally realized what had drawn me as a youngster to the charismatic actor — Tony Perkins was as queer as a the proverbial three-dollar bill. From show-biz obsessed new gay chums, I heard about his legendary promiscuity, including his affairs with Tab Hunter, Rudolph Nureyev, Stephen Sondheim (with whom he co-wrote the film “The Last of Sheila”), and the longest-running one he’d had — with the dancer and choreographer Grover Dale. I also learned that Perkins was deeply closeted (though his penchant for his own sex was an open secret in show-biz circles) and self-hating. Perkins subjected himself to a series of psychiatric attempts to “cure” his homosexuality, even going so far as to submit, in 1972, to electroshock aversion therapy, right at the moment the gay liberation movement was smashing the taboos on homosexuality, making front-page news, and forcing open many closet doors.

He finally managed to have his first sexual experience with a woman at the age of 39, bedding Victoria Principal, his co-star in “The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean” — a dalliance later confirmed by the actress. The following year, he married model and photographer Berry Berenson — the granddaughter of legendary fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli and sister of the jet-setting model-actress Marissa Berenson — with whom he produced two sons. The “cure,” of course, didn’t take, and he continued to have countless same-sex affairs, primarily with young men, until he died of AIDS in 1982.

The electroshock treatments took a terrible toll on Perkins — the talent that made him sought after by such distinguished film directors as Claude Chabrol, Jules Dassin, and Orson Welles faded away, as did his looks. My childhood fascination with Perkins faded as well, and since my early gay liberation days and his electroshock treatments he’d seemed to me a tragic figure, one to be pitied rather than admired (though the great historian and essayist Martin Duberman, in his candid 1991 “Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey,” makes amply clear how our homophobic culture compelled so many otherwise intelligent people to seek similar phony transformations).

A new memoir, “L’homme de passage: une histoire d’amours” (“The Transient: A Story of Loves”), published this spring in Paris, recounts the tale of a young man whose life was utterly changed after being seduced by Perkins, with whom he had a three-month affair. The author, Patrick Loiseau, has for the past four decades been the partner of a popular, Dutch-born French singer, Wouter Otto Levenbach, who goes by the single name Dave.

Dave first came to public prominence as the star of the French version of the musical “Godspell,” in which he had a critically acclaimed three-year run, followed by any number of million-selling hit singles in the 1970s and ‘80s. His sharp-tongued wit and self-deprecating humor have made him a regular guest for decades on all the important French TV and radio talk shows and, at times, host of his own programs. His looks and voice largely undiminished, he made headlines in the past decade when he became the first well-known show-biz personality to enter into the French version of a civil union, with Loiseau, who is also his lyricist. The couple, often seen together on the talk-show circuit, have recently been appearing on behalf of Loiseau’s new book, which is steadily climbing the French best-seller lists.

“L’homme de passage” would never be classed as great literature, but I found it quite touching and revealingly honest. In October 1970, Patrick was 20 years old and a virgin, earning a modest living as a salesperson in Yves St. Laurent’s men’s boutique in Saint Germain des Prés on Paris’ Left Bank. With a decent middle-class education and as the only one at the store proficient in English, it was his lot to wait on celebrities such as Peter Sellers and Greta Garbo.

Still, as the French say, he was ill at ease in his skin. He hated his nose, his chin, his eyes — his whole face, in fact — and his too-thin body; as a teenage vegetarian, he’d been hospitalized by his parents for anorexia. Patrick had neither girlfriends nor boyfriends, and his only homosexual encounter came when, struck by an urgent need to pee, he’d gone to relieve himself in one of Paris’ now vanished Vespasians — odiferous open-air urinals. There, he was simultaneously groped by two older men, which shocked and repulsed him so much he zipped up before climaxing but wet his pants and shoes as he fled. (In Edmund White’s admirable anthology “The Faber Book of Gay Short Fiction,” poet Alfred Corn’s marvelous short story “In Praise of Vespasian” makes clear just what went on in those legendary pissoirs.)

Patrick was less successful in escaping the troubling thoughts that certain men inspired in him; his instinct to see those yearnings as sick and depraved only added to his self-loathing. Photos of him from that time show he was an extremely attractive, long-haired, and willowy blonde boy whose androgynous looks earned him the nickname “ma feé” (my fairy, which in French is not a pejorative) from the aging closeted fashion queen who was the St. Laurent boutique’s manager.

One day Perkins, in town to make “Quelqu’un derriere la porte” (“Someone Behind the Door”) for the Franco-Hungarian director Nicolas Gessner, came in to buy pants needed for the film. It was Patrick who waited on him, taking his measurements and kneeling to pin the garments to be tailored. As Perkins left, he said, “By the way, your name is Patrick, isn’t it? I’m Tony!,” and with a flashed smile and wave of a hand was out the door.

To Patrick’s astonishment, the day after the clothes were delivered to Perkins’ hotel, the store manager got a phone call complaining the pants didn’t fit. But when Perkins showed up and the pants were once again put on him, he pronounced them “perfect after all” and, to excuse himself for the unnecessary disturbance, asked Patrick to choose some shirts and sweaters for him. He also slipped a piece of paper into Patrick’s hand and whispered, “I hope I didn’t get you into any trouble, but I just had to see you again.” The paper contained just the name Tony — with his phone number.

After agonizing for two days about whether to call the captivatingly handsome 38-year-old star, Patrick worked up his courage and dialed the number. It turned out to be that of a luxuriously appointed apartment Perkins had borrowed from a friend, to which Patrick was immediately invited for dinner. Thinking himself unworthy of such attentions, Patrick was discombobulated when, in time, Perkins cupped the boy’s head in his hand and, intoning the words “Patrick, you’re sooooo sexy!,” kissed him long and deeply, the first man to ever have done so. Perkins began slowly undressing the trembling youth, who quickly began to help him do so — and they made love. Nearly every night for the next ten weeks, they arranged to get together, and when the time arrived for Perkins to go to London for additional filming, he promised to be back in a few weeks to dub the French version of the movie.

Sadly for Patrick, one day he got a call from Perkins, who told him he was returning to New York and to write him. Patrick was, by this time, deeply in love for the very first time, and fell into a profound depression, eventually sending Perkins three plaintive letters telling him how destroyed he felt.

Finally he received a reply.

“Dear Patrick,

“I know that you must be asking yourself WHY I haven’t written, but when I explain I’m sure you’ll understand.

“Because you’re too intelligent to be just a salesperson in a boutique, and if you only had the mentality, the sensibility, and the capacities of a sales clerk, you and I would never have gotten together. So, why haven’t I written?

“Because I was waiting to get a letter from you — your inevitable letter of disillusion, which would say, ‘Okay, I want just to let you know that my eyes have finally been opened. I see clearly now that you never had any real feeling for me, and that I was only an occasional nothing that you couldn’t forget quickly enough. Thanks anyway — I want you just to understand that ‘I DON’T THINK I NEED YOU ANY MORE!’ But I’ve not as yet had such a letter from you.

“However, even if you’ve only THOUGHT of writing me a letter like that, that’s good enough for me. All that is a long and complicated way for me to tell you that you must know that you don’t really ‘need’ me, as you’ve said in each of your letters — that makes no sense! You live in France and I live in America, and that’s not going to change any time soon. And when you wrote me that you refused all New Year’s Eve invitations to stay alone at home and think of me, that makes me sad — because it doesn’t correspond to the image I have of you at your best: INDEPENDENT, STRONG, AND ADULT. Do you think I find you attractive because you’re feeble, dependant, and adolescent? You’re better than that, and you mustn’t miss me — even though it would be awfully easy for me to miss you. I think about you too, but hoping that I’ll be in Paris again soon — and you’re the first person I’ll call (from the airport!).

“Thanks for the gift. That scarf: the only thing I can say is that each time I throw it around my shoulders I think of you, and I will never, ever lose it.

“Have you understood this letter? Will you write me soon?

“Affectionately,

“Tony.”

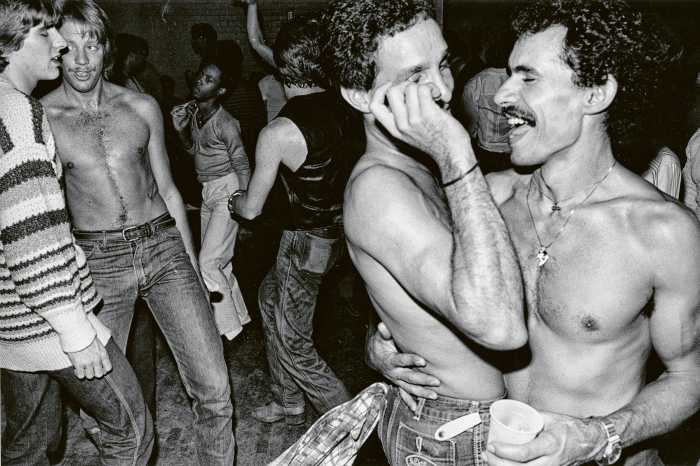

It took a few more months for Patrick to more or less heal, at least enough to allow himself to be persuaded to join a young female friend in an outing to a crowded and smoke-filled night club in the Latin Quarter, where a handsome young beatnik singer from Holland was eking out a meager living by singing and playing the guitar, then passing his hat to collect tips from the customers. When he came by the table where Patrick and the girl were sitting to collect his tip, he gave the young blonde boy a ravishing smile — and then, some minutes later, having finished amassing all the francs he could, came back to their table, put his arm around Patrick, and asked, “Do you like boys? My name’s Dave.” They have now been together more than 40 years.

Irony of ironies, it was his brief affair with the self-hating American movie star that gave the self-hating French boy enough of a sense of self-worth to be able to accept and return the affection that Dave soon showered upon him. If he’d been used as a sexual Kleenex by Tony, at least he’d been used elegantly and charmingly.

Tony and Patrick would not see each other for another five years, when Patrick and Dave were on a visit to New York to meet with the execs at CBS Records, where Dave was then under contract. On a chance impulse, Patrick dialed an old New York phone number given to him by Perkins, who was then on Broadway starring in “Equus.” The French couple found it impossible to get tickets to the sold-old hit before their scheduled departure, but when Berry Berenson answered the phone she exclaimed, “You’re Patrick from Paris? Tony will be so happy to see you. There’ll be two tickets for you and your friend waiting at the theater box office tonight, and I’ll leave word for you to be admitted back stage to his dressing room.”

After the play, Patrick and Dave did indeed go back stage, but instead of knocking on Perkins’ dressing room door, they diffidently decided to wait for him to come out. When he did, he was wearing the scarf Patrick had given him all those years before… and in the background lurked another young blonde boy who did not look unlike Patrick. Still, the smile on Perkins’ face on seeing Patrick Loiseau and meeting his lover Dave was broad and genuine. Perkins’ letter of rupture had achieved some effect on the young Frenchman after all.

L’HOMME DE PASSAGE: UNE HISTOIRE D’AMOURS | By Patrick Loiseau | In French | Editions Didier Carpentier | editions-carpentier.fr | 19.5 Euros; 269 pages