A US district judge issued a preliminary injunction on July 15 barring the US Departments of Education (DOE) and Justice (DOJ) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) from enforcing the Biden administration’s formal guidance documents issued in June 2021 concerning discrimination because of sexual orientation or gender identity.

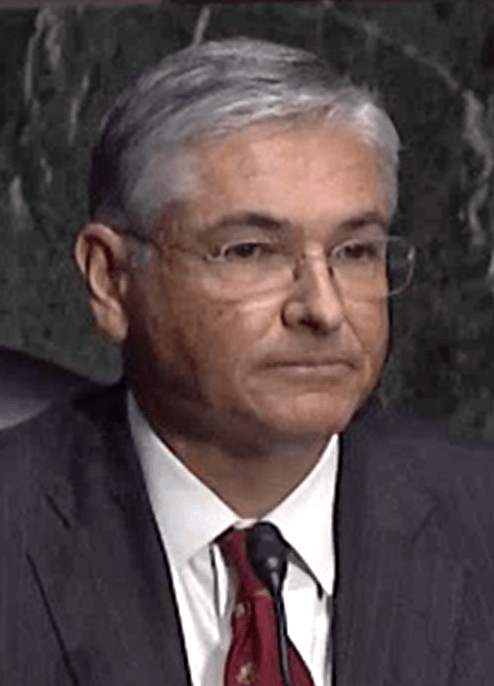

Judge Charles E. Atchley, Jr., issued the ruling in response to a lawsuit brought by 20 state and an association of Christian schools challenging the guidance under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.

Atchley was nominated for the federal bench by former President Donald Trump in September 2020 (and was confirmed by the Senate in December 2020 after Trump was denied re-election) during the lame duck session of the Senate as part of Senator Mitch McConnell’s effort to confirm as many Trump-nominated judges as possible while Republicans still had a Senate majority, which they lost early in January.

The plaintiffs, led by Tennessee, argued that the Biden Administration violated the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) by publishing these guidance documents without going through the required APA procedures for adopting “legislative rules,” and that the administration’s reliance on the Supreme Court’s ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) was not warranted. They also claimed that these guidance documents intruded improperly on the states’ ability to enforce state laws and regulations regarding restroom use in public accommodations and schools, as well as women’s sports participation. About half of the plaintiff states have already legislated against transgender people on one or both of those issues.

In the Bostock case, the Supreme Court reviewed decisions from three circuit courts of appeals on the question of whether Title VII’s ban on employment discrimination “because of sex” included claims of discrimination because of sexual orientation or “transgender status.” The Court answered yes, in an opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, who used a “textual analysis” of the statute to conclude that it was impossible to discriminate against somebody because they are gay or transgender without discriminating because of their sex, so these discrimination cases should be dealt with as sex discrimination cases.

However, Justice Gorsuch explicitly limited the scope of the court’s decision, pointing out in his opinion that the three cases all involved claims that an individual was discharged because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. He made the point that the court was just deciding whether Title VII applied to such claims and was not addressing whether the same interpretation applied to other statutes or to other forms of discrimination. He also said the cases before the court did not present issues about which restrooms an individual could use, how they could dress, or any of the other questions that can arise in cases involving transgender status. In that sense, Bostock was a narrow ruling as a controlling Supreme Court precedent.

On the other hand, the logic of the case at a more general level appeared broad. Although the immediate response by the Trump Administration was to give the opinion a narrow reading focused on Title VII cases, litigants in other cases pressed lower federal courts to apply the Bostock reasoning to cases under Title IX, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Fair Housing Act, the Fair Credit Act, and state and local sex discrimination laws.

On the day he was sworn in as president, January 20, 2021, Joe Biden issued an executive order embracing a broad reading of Bostock and directing federal agencies that enforce bans on sex discrimination to apply that ruling under their statutes. Responding to the president’s directive, the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission issued formal documents in June 2021 setting out an interpretation and enforcement agenda for advancing LGBTQ equality.

Both agencies took a broad approach. For example, the EEOC said employers would be required to allow employees to use restrooms and locker rooms consistent with their gender identity, to protect transgender employees from being subjected to a “hostile work environment,” and to use appropriate pronouns. The DOE’s Office of Civil Rights issued similar guidance, including requiring schools to allow transgender girls to participate in women’s sports competition. Both agencies explained that these guidance documents did not have the effect of law, but that they contained the interpretations that the agencies would rely upon when investigating discrimination complaints and bringing enforcement actions in the courts.

The states filed their lawsuit within months of the publication of the guidance documents. Then they asked the district court in September 2021 to issue a preliminary injunction, blocking any investigative or enforcement action until a ruling on the merits of their case. Judge Atchley took nine months to consider the motion before issuing his ruling on July 15, at the same time denying a motion by the defendants to dismiss the case.

The government, pointing out that it has not initiated any enforcement actions against the plaintiffs, argued that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring this “pre-enforcement” lawsuit, that the guidance documents are not “regulations” that can be attacked under the APA, and that state governments and school districts could raise their arguments as defenses in any enforcement actions in the future. Judge Atchley rejected the government’s arguments with a detailed analysis showing that federal courts have allowed states in the past to challenge similar sorts of agency position documents that posed threats of future enforcement.

One of the important components of standing to sue is for the plaintiff to show that the government’s action threatens to harm them in some concrete way. Tennessee pointed out that millions of dollars in federal money for the state’s educational institutions was potentially at stake because Title IX applies to schools that receive federal financial assistance and violations can be punished by suspension of such assistance. Those states that have already legislated to bar transgender people from various activities pointed out that the guidance documents threatened them with federal enforcement action if the states enforced their own laws, thus impairing their state sovereignty. An improper impairment of state sovereignty has been held by federal courts to be an irreparable injury to the state.

In order to get a preliminary injunction, a plaintiff has to show that there is a likelihood that they will win their case on the merits. Judge Atchley found that the states met that test by focusing on Justice Gorsuch’s statements in the Bostock opinion that appear to limit its precedential scope. He also noted that a federal court in Texas has already issued an injunction along similar lines in a lawsuit brought by that state against the government, but that preliminary injunction focused only on potential enforcement action against Texas.

Because of the way Title VII and Title IX are enforced, this injunction does not mean a total shutdown on enforcement of those statutes in LGBTQ discrimination cases while this case is pending. Individuals can bring lawsuits under both statutes. Under Title VII, after filing a charge with the EEOC, an individual can request a letter from the agency allowing him or her to file their own lawsuit. Under Title IX, an individual can start litigation directly without filing anything with the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights.

Despite the limiting language in the Bostock opinion, several federal district courts and courts of appeals have already ruled that the logic of Bostock can be used in cases under Title IX, the Fair Housing Act, and the Affordable Care Act. For example, several district courts have ruled recently in favor of transgender employees seeking coverage for gender-affirming care for themselves or their family dependents under public employee benefit plans, and for several years most district courts confronting the issue have ruled in favor of transgender students seeking equal restroom access. Those courts have relied not only on Title IX, Title VII, and in some cases the Affordable Care Act, but also on the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution, which comes into play in state government employee cases.

Also, several courts have used the Bostock reasoning to extend state law protection against discrimination to LGBTQ plaintiffs in states that ban sex discrimination without explicitly covering sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination claims in their statutes.

In a case long pre-dating Bostock, federal courts in Virginia ruled that a transgender boy, Gavin Grimm, suffered illegal discrimination when he was barred from using boys’ restrooms at his high school, and after the Bostock ruling, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals found it easy to affirm that decision. The Supreme Court denied the school district’s petition to review that decision.

Judge Atchley’s ultimate decision on the merits will also have to pay attention to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals’ ruling in R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes v. EEOC, affirmed by the Supreme Court in Bostock, holding that a funeral home discriminated against a transgender employee when it discharged her for refusing to comply with the employer’s gendered dress code.

The government can appeal Judge Atchley’s order to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.