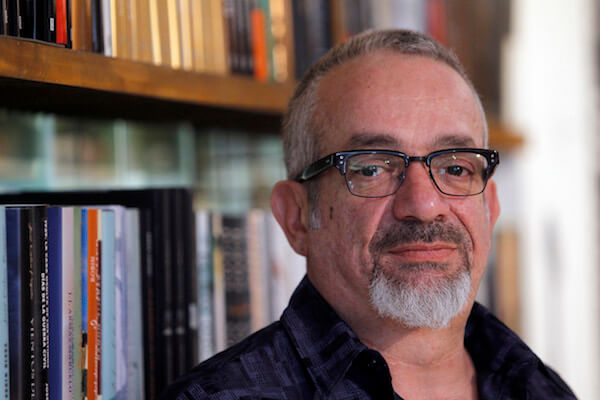

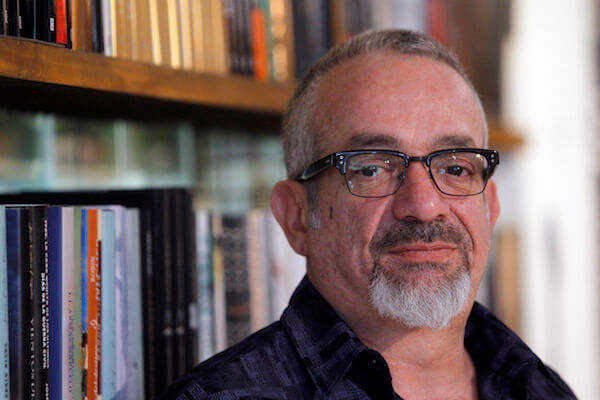

Before he became an acclaimed novelist, Rabih Alameddine studied engineering at the University of California, got a master’s degree in business, went back to school to study clinical psychology, and then had a successful career as a painter, with solo exhibitions in New York and London. He became a fulltime writer in 1998, with the publication of his first novel, “Koolaids.” Alameddine followed that book with a short story collection, “The Perv: Stories” (1999), “I, the Divine: A Novel in First Chapters” (2001), “The Hakawati” (2008), “An Unnecessary Woman” (a 2014 National Book Award finalist), and in October, “The Angel of History: A Novel.”

Alameddine, 57, was born in Amman, Jordan, to Lebanese Druze parents, was raised in Beirut, and, before immigrating to the United States, studied in England and Kuwait. He’s drawn on his wide-ranging experiences for his novels: Osama al-Kharrat, in “The Hakawati,” leaves his family in Beirut to study engineering in Los Angeles; Mohammed, in “Koolaids,” is a gay Lebanese painter who exhibits his work abroad; and Jacob (born Ya’qub), the protagonist of “The Angel of History,” is a gay Arab immigrant living in San Francisco, Alameddine’s adopted city.

The correspondences between Alameddine’s fiction and his life notwithstanding, his books are not merely autobiographical. They instead are richly imagined and superbly written works that dive headlong into our chaotic contemporary world and, through the enchantment of storytelling, give form and meaning to lives fragmented by violence, displacement, and disease. “Koolaids” portrays the impact of both AIDS and the Lebanese civil war on a group of families and friends in Beirut; in “The Angel of History,” the Yemeni-born Jacob, tormented by his memories of loved ones lost to AIDS and by the present-day war in his homeland, commits himself to a psychiatric ward in a San Francisco hospital. Alameddine’s novels combine realist narrative, epic tales, fantasy, and surrealism, with a radical political sensibility. As the Guardian noted in its review of “The Angel of History,” “At a time when many Western writers seem to be in retreat from saying anything that could be construed as political, Alameddine says it all, shamelessly, gloriously and… in the most stylish of forms.”

Rabih Alameddine’s new novel explores modern culture’s refusal to remember

During a recent interview, I spoke with Alameddine about his latest novel, his love for the German-Jewish Marxist literary critic Walter Benjamin, the “othering” of Arabs in Western societies, and contemporary gay life, among other matters.

In “The Angel of History,” two archetypal figures — Satan and Death — struggle to claim the anguished Jacob’s soul. The former represents memory and remembering; the latter, forgetting and oblivion. There’s no contest as to which is the more appealing figure. Satan is a lively, witty figure given to campy remarks whereas Death — Satan’s son — is gloomy, albeit compassionate (“Forgetting is good for the soul… Not just good but necessary”). Their philosophic duel constitutes the novel’s central dialectic.

Why did Alameddine choose to personify remembering and forgetting through these two figures?

“With Death, it was easy — in terms of mythology, you have to forget your life before you go to the underworld,” he explained. “Death is the one who gives you the cup [of forgetfulness]. Satan is the first rebel, the first to say ‘no.’ In the story in the Quran, God created the angels and they were happy. Then he created this thing — man— from clay, from dirty clay, and God asked the angels to bow down before him, so that it was no longer just bowing before God, you have to bow before man. And Satan said ‘no.’ And that’s it, who do we bow to, and who are we rebelling against. Satan becomes for me not just the angel of queers; he becomes the angel of adolescence, the angel of every revolution, of all those who say no. I started with this idea and then I fell in love with him. Yes, just say ‘no!’

Author Rabih Alameddine. | BENITO ORDONEZ/ RABIHALAMEDDINE.COM

“If you ask me what the book is about, it’s this tension between remembering and forgetting, not about AIDS. I used AIDS because that’s what I know. I’m much more interested in how we remember and how we forget than the details of AIDS. You can’t remember without forgetting and you can’t forget without remembering. So, it’s a dance between the two. The unfortunate thing for us these days is that we live in a culture that is really into forgetting. Everything is geared to us moving on and forgetting. In the book, I have Satan quote Gore Vidal about this country being the ‘United States of Amnesia.’ So, I think where we are right now is unhealthy, although I’m not exactly sure what would be the right balance.”

The novel’s title comes from Walter Benjamin, whom Alameddine claims as a literary hero and inspiration. In a famous essay, Benjamin ruminates about a Paul Klee painting, “Angelus Novus,” which, Benjamin writes, “shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.”

Benjamin, said Alameddine, “sees how modernity, the rush toward progress, was leaving so much in its wake and no one having any time to grieve. It fascinates me that this angel is looking backward, not forward. Now, if we spend all our time looking backward we can’t move forward. But we’re not looking backward at all these days, it’s as if no one remembers anything.”

Alameddine cited an ill-considered remark by Hillary Clinton during the 2016 presidential campaign to make his point: “I know she apologized for it, but Hillary saying Nancy Reagan was a leader in talking about AIDS — oh, fuck off — but she never would’ve been able to say that if there actually were reminders.”

“The Angel of History” is full of reminders about the worst years of the epidemic, passages that no doubt will disturb those who experienced them. Once-healthy, vigorously sexual young men become emaciated invalids. The homophobic mother of a man who dies from AIDS raids the apartment her son shared with his lover and steals their furniture and possessions, including their books. Tortured by guilt over being uninfected and healthy while friends die all around him, Jacob seeks oblivion in a harrowing, racialized sadomasochistic encounter.

In the present, Jacob explodes with rage at young gay men who never experienced the plague years. He meets two “artistes of the nouveau-bland movement whose manifesto consists of defending the rights of white gay boys to have dating anxieties and live homo-happily ever after.” When one expresses sympathy for Joan Didion over the death of her husband, Jacob feels as if “alarm bells woke me from a twenty-year nap.”

“Her husband died?,” Jacob says. “You think that’s horrifying? You feel sorry for her? She’d lived a full life. I had six friends die in a six-month period, half a dozen of my close friends including my partner. We were nothing but babies, where was she when we were dying, where were you, you motherfuckers?”

I asked Alameddine whether Jacob’s rage is his, and whether writing “The Angel of History” dredged up the furies of anger.

“I’ve had bouts of anger at many things,” he responded. “I went through a similar process. He begins by being angry at young gay men, but then he realizes that he’s the one who forgot, not them. They didn’t forget, they didn’t even know. They weren’t there. The problem is that he has allowed the world to move on, and so have we, our generation. We did because we wanted to move on, we wanted to be able to live rather than wallow in our misery. The trouble is we went too far, politically speaking, we wanted to be accepted by the dominant culture rather than being opposed to it. If we are to be accepted by the dominant culture, we can’t make them feel bad. So yes, Jacob is upset about the young gay boys but he really was more upset with himself about what he has given up to be able to move forward.”

Does Alameddine, like Jacob, believe that assimilation into mainstream American life and opposition to assimilation are the two polarities of contemporary gay male life?

“I don’t know about the two polarities, I’ve always believed in multiple polarities, but those are two,” he said. “And I don’t know if they are in opposition because I have met guys who live behind picket fences during the day and go out and become freaks at night. Who are we? — that’s the issue. The important thing for me even in the early days wasn’t so much about being gay, it was about being outside the dominant culture, in stark opposition to what is considered normal. That’s where I stood, as a gay man, as an Arab, I do not fit into what people want me to. For me that has always been the struggle. Unfortunately for where we are heading is that gay is normal, so that those of us who never felt normal are outside that conversation. The main movement of contemporary gay life is that we are just like you except for a few minor things. And I am not. Most of my friends are not, whether they’re gay or straight. So where do we fit in? I don’t think we’ve figured that out yet.”

In “Koolaids,” Alameddine writes, “In America, I fit but do not belong. In Lebanon, I belong but I do not fit.”

“This tension between fitting in and not belonging and vice versa is the theme of all my books,” he said. “Dislocation, this feeling that you are part of society but that you are also outside of it. A lot of us who live on the margins feel that.

“Part of the reason I belong in Lebanon is that it is where I grew up, my family is there, I am part of its history, but I don’t fit. Here I certainly don’t belong and am beginning to wonder if I ever did fit.”

Alameddine deplores how in the United States and other Western societies, Arabs and Muslims are “rendered the ‘other’ in almost every way.”

“I don’t have to go through all the movies that portray us as just incredibly different,” he said. “I wrote an op-ed piece almost 10 years ago about the use of the word Allah. Allah is just ‘God’ in Arabic. In Lebanon, Christians pray to Allah, Jews pray to Allah, everybody prays to Allah, it’s just a word. Here it becomes the Muslim God, different from the regular God. We never say French people pray to ‘Dieu’ or Mexicans pray to ‘Dios,’ but Arabs pray to Allah. We are different, we are the other.”

Alameddine indicts the West for much more than cultural bias. In “The Angel of History,” Satan remarks, “The supremacy of Western civilization is based entirely on the ability to kill people from a distance.” One of the novel’s most brilliant sections, “The Drone,” personifies US military involvement in the Middle East through an unmanned aerial weapon that crashes in a desert. Alameddine gives the drone consciousness (if not self-awareness); it destroys lives and property but thinks of itself as bringing modernity and civilization.

“Western involvement in the Middle East is destructive,” Alameddine observed. “But many of us who grew up in a postcolonial country idolized the West, too.”

He added, “As much as I make fun of this country, it has an amazing capacity to accept weirdness. As much as we attack others, it is more accepting, relatively speaking, than a lot of other places. We have to keep that in mind, we don’t want to lose that.”

In “The Angel of History,” a furious Jacob rants about San Francisco, singing a bitter but hilarious aria of alienation that begins with his observations about an upscale restaurant that “was pretentious like everything in this drippy city that brimmed with self-congratulation, and the waitstaff were obnoxious and the customers more so and I so hated San Francisco. Oh, I live in the city by the bay, so I must be cool, I live in a cretinous provincial dump surrounded by pretentious superficially amicable cretins, aren’t I wonderful?”

Is Jacob here speaking for his creator, who has lived in San Francisco, on and off, since 1982?

“I see the entire world that way, but yes,” Alameddine replied. “At the same time, I love San Francisco. There’s a reason why I’m here. It’s just that, God, sometimes it really drives me crazy. It depends on the day, I guess. But I don’t know any New Yorker who doesn’t understand this feeling.”

THE ANGEL OF HISTORY | By Rabih Alameddine | Atlantic Monthly Press | $26 | 304 pages

For more information on Rabih Alameddine and his work, visit rabihalameddine.com.