Evita-inspired fashion designs by Roberto Piazza during a runway fashion show in the Buenos Aires City Legislature Building on July 26, 2012, the 60th anniversary of Evita's death. | MICHAEL LUONGO

As Evita lay dying of cervical cancer in the presidential residence in 1952, her skin sallow and thin, a man sat with her, whispering, “To be a faggot, to be poor, what they say of Eva Peron in this ruthless country is the same thing.”

Eva was in shimmering white, foreshadowing the ghost she would soon become. She touched the man’s shoulder and answered delicately, sadly, “I think you are right, Paquito.”

It’s one of the most important scenes in “Eva Peron: The True Story,” starring Argentine actress Esther Goris. The 1996 movie was Argentina’s middle finger to Madonna, who was then in the country bringing Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice’s musical to the screen.

But did this remarkable exchange between Evita and Paco Jamandreu, a defiantly out gay man and the famous first lady’s favorite dress designer and confidante, ever happen?

“This is a lie,” according to Osvaldo Bazán, the author of “Historia de la Homosexualidad en la Argentina,” a more than 600 page tome that takes readers from the pre-Columbian era to that nation’s 2010 same-sex marriage law.

Maria Eva Duarte de Peron, wife of Argentine President Juan Domingo Peron and best known to the world as Evita, is a gay icon to many. She was made that way largely because of the women we gay men love who have played her on stage and on screen –– Patti LuPone, Elaine Paige, and Faye Dunaway, as well as Madge. Evita is even the name of one of Tel Aviv’s most popular gay bars. Bar co-owner Shay Rokach said it was named for her because “Eva Peron was involved in charity and a supporter of the human rights. Evita as well is a central pole in the LGBT community.”

In Argentina, though, Evita’s status as a gay icon is more complicated. It’s true she surrounded herself with gay men, perhaps almost from the time she arrived in Buenos Aires in 1935 as dreamy-eyed teenager Eva Duarte –– poor, uneducated, and illegitimate –– up until her death on July 26, 1952 as one of the most powerful women who ever lived. But it’s this power as the female half of a political couple that founded the Partido Justicialista, better known as Peronism, that has done her in at home. She’s too divisive. Half the country, gay men included, adore her. Among many of the rest, especially upper class Argentines, she’s hated.

As a political wife, Eva Peron is often compared to Hillary Clinton, also a gay icon with a solid pro-LGBT record as secretary of state. Christopher Andersen even wrote a book about Clinton called “American Evita.” But if you really want to understand why many Argentines are puzzled when foreign gay men say they see Evita as a gay icon, think of her like Nancy Reagan. Nancy had the right elements. An actress whom gossip said was hardly chaste, a clotheshorse with gay designer friends. But her husband’s genocidal approach to AIDS means Nancy will never bear the gay icon crown, even among Log Cabin Republicans. It’s within this political context –– and not the hazy glitz of stage, screen, and song –– that outsiders must consider Eva Peron’s twisted history as a gay icon, then and now, in Argentina.

Evita and Her Gay Friends

Maria Belen Correa, an Argentine transgender activist and performer, channeling Evita Peron during the stage show held after the 2008 Buenos Aires Gay Pride Parade. | MICHAEL LUONGO

“This is not the theme,” Bazan said when asked what impact Evita’s friendships with gay men had on gay life in Argentina when she was alive. “Homosexuality was hidden then.”

Bazan thinks Goris’ deathbed scene rewrote Argentine history, perhaps with the intention of making Evita a gay rights heroine for a more tolerant audience. He said he spoke with screenwriter José Pablo Feinmann, a man he described as “a well known Peronist author, intellectual, close to power, and a friend of Cristina” –– Fernandez de Kirchner, Argentina’s current Peronist president, who often compares herself to Evita. Bazan explained, “It is very clear that Evita was a friend of Paco Jamandreu, and that Paco was gay. It is not certain that this conversation ever happened… Feinmann told me, ‘It’s a biography, it’s a film, it’s a fiction.’”

Feinmann did not respond to my request for comment.

Bazan added, “It’s certain that later, now, after the passing of the [2010 marriage] law,” LGBT rights groups take Feinmann’s scene as truth. That baffles Bazan.

“After the film, you could say she became a gay icon, but Peronism was very homophobic, absolutely homophobic,” he said. “For kids to form the group Putos Peronistas is a contradiction. We are talking about a political party established in a military coup, a military coup in Latin America by a pro-Nazi military general in the decade of the 1940s.”

The Putos Peronistas, an LGBT Peronist group, emphasizing transgender activism, marching in the 2010 Buenos Aires Gay Pride Parade. “Puto” translates roughly as “faggot.” | MICHAEL LUONGO

Still, Bazan added, “Without a doubt, there are other friends of Eva who showed very comprehensively to Eva the gay world.” He mentioned in particular, Miguel de Molina, a flamboyant, openly gay Spanish actor and singer. “This story of Paco Jamandreu is a lie, but Eva had a very close relationship with the gay world,” Bazan said.

A Miguel de Molina outfit, photographed at Buenos Aires’ Centro Cultural Recoleta in 2011. | MICHAEL LUONGO

A retrospective of Molina’s work last year at Buenos Aires’ Centro Cultural Recoleta left an impression of him as a male Carmen Miranda. Molina experienced the best and the worst of life in Argentina as an openly gay man. In 1942, on the heels of a sex scandal involving military cadets that launched a gay panic, Molina was arrested and deported, his play shut down, simply because he was openly gay. He soon returned, however, meeting Eva Peron in 1946. Thereafter, he remained close to her, even if Juan Peron did not approve.

“When Miguel de Molina would come to the Casa Rosada or to Olivos, he would annoy him,” Bazan said of Peron. Knowing Molina’s close relationship to the couple, the Spanish Embassy asked him to plan a party for them in 1948. Peron requested that Molina sing “La Otra,” which was identified with Molina’s main rival, Concha Piquer, and had no masculine form, its double-entendres emphasizing Molina’s homosexuality.

A thank you letter from Evita Peron to Miguel de Molina, a Spanish performer who was one of the lady’s gay friends. Photo taken at Buenos Aires’ Centro Cultural Recoleta in 2011. | MICHAEL LUONGO

Molina left Argentina in 1955, the year Peron was deposed, but later returned to Buenos Aires. A year before his 1993 death, he was inducted into Spain’s revered Order of Isabella the Catholic.

Molina was among the gay friends of Evita the famous, but even as an unknown, she befriended homosexual men. Among them was hairdresser Julio Alcaraz, who created her iconic chignon bun hairstyle. Like many of the gay men she met, he was with her until the end, styling the hair on her exquisitely preserved corpse, helping prepare her to be displayed like Moscow’s Lenin in a never-built tomb.

Interviews with Alcaraz informed the 1972 “Queen of Hearts” British documentary that inspired Tim Rice. Argentine writer Tomás Eloy Martínez referred to Alcaraz in his historical novel, “Santa Evita,” which itself was a mix of reality, myth, and conjecture. Martínez describes Alcaraz taking the awkward, struggling teenage actress under his wing. The novel’s protagonist, an investigative journalist, interviews Alcaraz, who shows him a bun from Evita’s hair. Years ago, Cesar Cigliutti, president of Comunidad Homosexual Argentina, told me the bun was a trick for a bad hair day emergency but became integral to the first lady’s style.

It’s not hard to imagine how in the 1930s Eva Duarte found gay friends. Buenos Aires was awash in Depression-era social upheaval, and Spain’s civil war made the city an epicenter for Spanish cultural figures. The most famous was gay playwright Federico García Lorca, whose plays were performed at the Teatro Avenida on Avenida de Mayo. García Lorca lived a few blocks away in the 1929 Castelar Hotel, in room 704, now a mini-museum. A brass plaque on the hotel’s entrance also marks his stay.

Once the city’s most glamorous street, Avenida de Mayo is lined with hotels, yet there’s a reason García Lorca chose this one. Decades before gay hotels like the Axel or El Lugar Gay, the Castelar was where homosexual visitors stayed, its Turkish sauna a draw. The sauna’s ancient wooden changing rooms, stained glass ornamentation, and even the wooden refrigerator behind the bar give a glimpse of what gay life, furtive and yet an open secret, might have been like when Eva Duarte boarded a train in Junin to bite into Argentina’s Big Apple.

The Modern Day Legacy Of Evita

Perhaps the most important Argentine maintaining Evita’s legacy is Gabriel Miremont, the out gay curator of the Museo Evita. Years ago, in an interview with him I did for Out Traveler, Miremont told me Evita connected with gay men because of her poor background.

“Both have the same problem, they stay beside the society, marginal,” he said, words similar to what Feinmann imagined passed between her and Jamandreu. Beyond Alcaraz, however, little is known about Evita’s earliest gay friends, Miremont said.

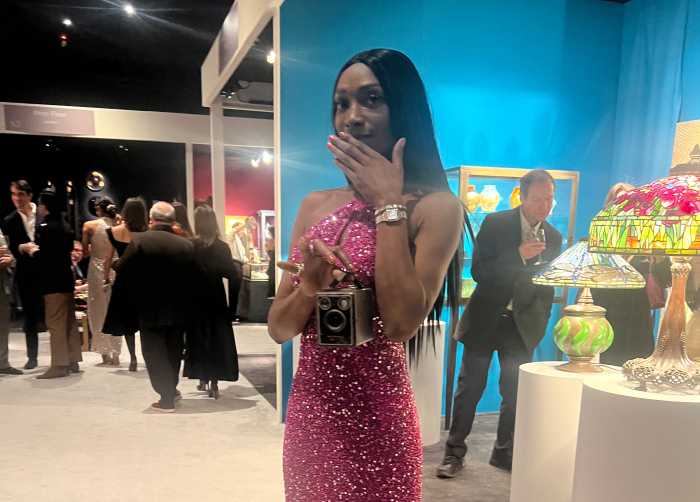

Gabriel Miremont, curator of Buenos Aires’ Museo Evita, with Cristina Alvarez Rodriguez, the great-niece of Evita Peron and president of the Eva Peron National Institute of Historical Research, at New York’s Consulate General of Argentina. Behind is a 1980 painting of Evita called “Grita” (“Scream”), by Nicolas Garcia Uriburu. | MICHAEL LUONGO

In New York this month to open the exhibit “Evita: Passion and Action” at the Consulate General of Argentina, Miremont acknowledged Evita is a gay icon in much of the world. Among gay Americans, though, he finds what he calls “the Barbie Evita” problem –– an overemphasis on clothes and glamour that grew out of the Lloyd Webber-Rice play and Madonna’s movie.

Miremont’s hope is in visiting the exhibit of Evita’s clothing and photographs and modern art inspired by her, glamour will be “the starting point, what you see first.” After that, he said, “you have to understand all her works, all the good she did for people. The way she changed the society.” Miremont has always told me that while “Evita,” the play, “as a work of art is beautiful,” he does not feel it is historically accurate.

In fact, while the song “Don’t Cry for Me” is now often performed even at official government events in Argentina, the full play has never been formally produced there. This is not because of those who hate Evita, but instead because her admirers are offended by the “Goodnight and Thank You” scene where Eva entertains a revolving door of men.

Miremont credited the current Broadway revival, directed by Michael Grandage –– which boasts the greatest gay quotient ever, with Ricky Martin playing Che –– with more accuracy. When he saw it in London in 2006, women were inaccurately shown voting in 1946, a year before they gained their suffrage. He was pleased to see women sadly pass ballot boxes while men voted in Grandage’s latest production.

To be sure, Argentine hearts have undoubtedly been softened by Buenos Aires native Elena Roger’s star turn as Evita, both in the West End and on Broadway. Miremont said he was pleasantly surprised in conversations with Michael Cerveris, who portrays Juan Peron, how well versed the actor was in Argentine history.

A dress that Argentine designer Paula Nateloff made for Evita Peron, part of “Evita: Passion and Action,” at New York’s Consulate General of Argentina through September 28. | MICHAEL LUONGO

Despite Miremont’s worries about the emphasis in “Evita” on fashion, for some gay Argentine men her glamour and the relationship it had with social issues are equally important. Designer Roberto Piazza is one half of an Argentine power couple; his wedding to Walter Vázquez was a major news event in Buenos Aires. Piazza said he finds creative inspiration from both Evita and Jamandreu, whom he knew personally before his 1995 death. For the 60th anniversary commemorations of Evita’s death, Piazza presented a spectacular collection of clothing inspired by Evita, Jamandreu, and Dior in the Buenos Aires City Legislature Building. The show’s runway passed over an area where Evita’s body laid in state during Argentina’s two-week mourning period in 1952.

Regarding Evita’s legacy, Piazza explained, “Much of the history is inspired by sources that are at times contradictory –– from her extremely luxurious style [to the fact that] Evita was very much a woman of the people.” Through fashion, he said, Evita supported the work of her gay contemporaries.

“She loved gay people and cared for and protected Paco through a thousand aberrations that she did,” Piazza said. “And today she has become a major icon for the gay people.” However, he added, “I do not believe she is a gay icon. I believe she is an icon for all of society.”

Evita and Argentina’s Same-Sex Marriage Law

Buenos Aires’ gay pride march begins in Plaza de Mayo, in front of the Casa Rosada and Evita’s balcony. It continues along Avenida de Mayo, passing García Lorca’s Castelar Hotel to Congreso, where a rally is held just yards from the city’s tiny, virtually unnoticed AIDS memorial.

The last time I photographed the parade was in 2010, the year the gay marriage law passed. A few floats commemorated Juan and Evita Peron, linking them to Néstor Kirchner, the former president who had died days before, and his first lady, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who was by then president.

A few months before, on July 21, standing between portraits of Juan and Evita in the Casa Rosada, Fernandez signed the bill making marriage equality the law of the land, propelling Argentina into the front ranks of nations on LGBT rights. Fernandez even evoked Eva Peron in her speech, saying she knew what it felt like for Evita when women gained the right to vote. Cheering in the audience was Esther Goris, whose version of Evita was a prediction of sorts for that happy day in the life of gay Argentina.

Were the real Evita alive, would she too have cheered Fernandez on? We will never know for sure, but both the myth and reality of Evita strongly suggest the answer is an unqualified yes.

EVITA: PASSION AND ACTION | Consulate General of Argentina | 12 W. 56th St.| Through Sep. 28 | Mon.-Fri., 10 a.m.-5 p.m. ; Sep. 22-23, 9:30 a.m.-5 p.m. | Free and open to the public | 212-603-0443