“I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly. I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something,” Edward Gorey once declared of himself.

Or is it selves?

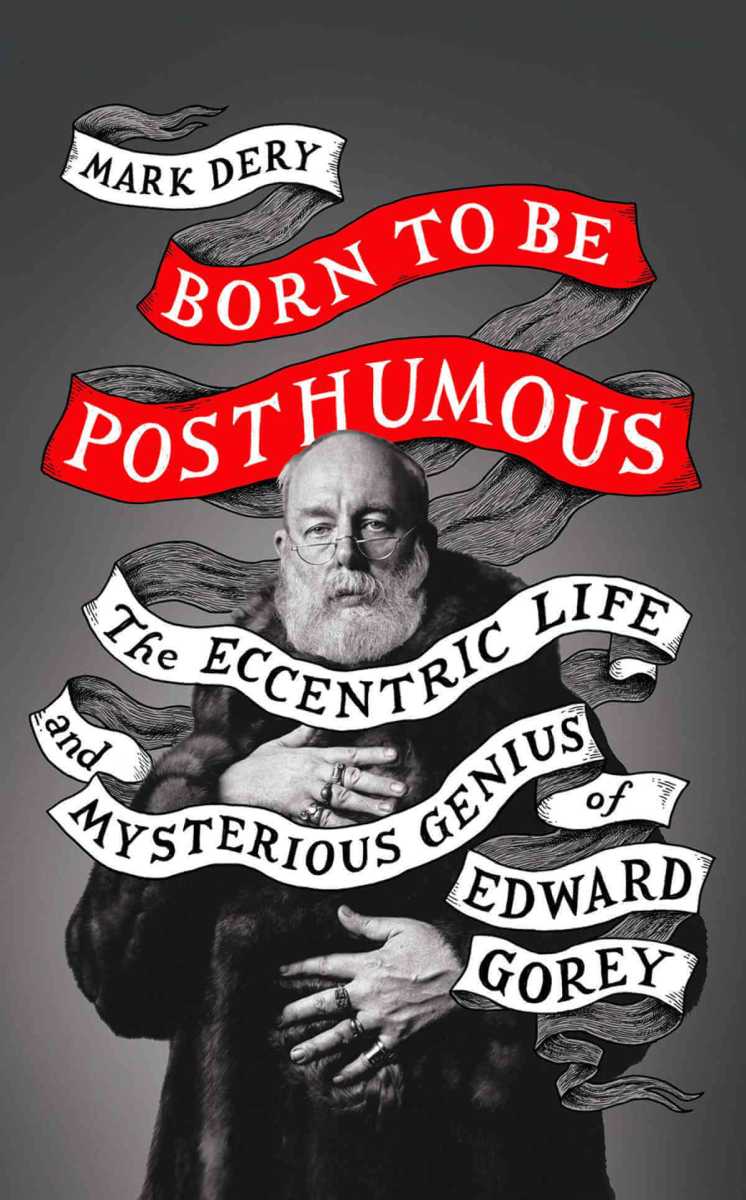

For in his marvelous new biography “Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey,” author Mark Dery shows how this prodigious illustrator of what might be called the tenderly sinister liked to maintain a soupcon of mystery about himself and his complex personality as much as his art. Assuming the aspect of an Edwardian gentleman, Gorey struck the perfect pose of the dandy — physically present but mentally in “a world of his own.” The problem was Edward Gorey wasn’t living in the 19th century.

Gorey was, whether he liked it or not, a man of the 20th century. Rareified on the surface, he was, just beneath it, popular with a general public well outside the confines of the baroque aestheticism that was his stock-in-trade. And while he was well-versed in the life and times of Oscar Wilde, Gorey would never have been sent to Reading Gaol for gross indecency or end his life in exile and social disgrace as Wilde did. Gorey ended his life in considerabe comfort on Cape Cod putting on puppet shows for children — not Wilde-like at all.

Life changed radically for the same-sex oriented over the course of Gorey’s time — even though he didn’t see himself as part of of that time or even all that gay.

“I’ve never said that I was gay and I’ve never said that I wasn’t,” Gory once declared with typical ambiguity. “What I’m trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else.”

He added, “Well, I’m neither one thing nor the other particularly. I suppose I’m gay. But I don’t identify with it much.”

In other words, Edward St. John Gorey (1925-2000) felt it was possible to be “out” and “stay in the closet” at the same time. In this, he’s in some ways a representative figure of what might be called the transitional era of gay American life — that period following World War II when homosexuality was a psychiatric category whose practitioners were subject to arrest if caught at it, lavender scares popping up in institutions of higher learning where being a homosexual was less welcome than being a communist. Gay wasn’t a topic for polite conversation. Yet as long as it wasn’t named it could flourish within the polite silence of the status quo. Andy Warhol achieved phenomenal success in this curious context. He was what would later be called openly gay in life and art. He even made s film called “Blow Job,” discreetly depicting a male hustler getting oral sex (the party of the second part remaining off-screen — the film being a medium close-up of the hustler’s face), yet this wasn’t talked about at the time.

Likewise, the sexuality of the far more decorous Gorey was undisturbed in this Don’t Ask/ Don’t Tell era. Stonewall changed all that — making gay a discussable mainstream topic. But it didn’t change things for Gorey. To those in the know, his sensibility was clearly gay, but his sexual life was as covert as his self was overt.

As Dery writes, “To nearly everyone who met him… his sexuality was a secret hidden in plain sight. There was the bitchy wit. The fluttery hand gestures. The flamboyant dress, floor-sweeping fur coats, pierced ears, beringed fingers, and pendants and necklaces, the more the better, jingling and jangling.”

But even setting this sartorial extravagance aside, Gorey’s gayness blazed away like a five-alarm fire for those who didn’t need Susan Sontag’s help in comprehending “camp.” To underscore this point, “Born To Be Posthumous” includes a rare picture of a shaven Gorey taken during his stint in the army (where he found relief from its dull routines in his discovery of the comic novels of E.F. Benson), The result finds him resembling none other than Christine Jorgensen. No, Edward Gorey wasn’t transgender. But he was what one might call transcultured — an American whose work was steeped in England and France while reflecting next to nothing about the land of his birth. Because of this cross-cultural sophistication, his flat Midwestern accent came as a shock to admirers meeting him for the first time

Few American artists, outside of Henry James are as European in outlook as Gorey. His illustrated chapbooks, whose titles include “The Hapless Child,” “The Doubtful Guest,” “The Curious Sofa,” “The Willowdale Handcar,” The Beastly Baby,” and, most dramatically, “The Gashlycrumb Tinies,” were carefully designed to ape everything English and antique with bone-dry comic undertoness. The result is Agatha Christie Meets Noël Coward in every way even though he only visited the UK once in his life. But the Great Britain of Gorey’s imagination was fully equipped with stories, characters, and above all images that Dery aptly cites as suggesting that their creator was a cross between Sebastian Flyte (“Brideshead Revisited”) and Holly Golightly (“Breakfast at Tiffany’s”). In other words, Gorey was an artistic fantasy come to life — a self-created individual enveloped in the aura of a literary fiction. Or, as Gorey put it, “I write about everyday life.”

The birth of Gorey’s sensibility is hard to pin down, He first read “Dracula” when he was eight, but few children who love the morbid make it as much a part of their life as Gorey did. Most eight year-olds have never heard of Bram Stoker and more likely have encountered the Count in the cinematic form of Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee. Gorey’s love of “Dracula” (which reached its apex late in his career) and his taste for the macabre was but one part of his artistic and personal life.

Dery sees the first full-flowering of the Gorey persona at Harvard where he roomed with poet Frank O’Hara. They decorated their digs with white lawn furniture and an unmarked gravestone and spent many an evening languidly trading bon mots listening to Marlene Dietrich records with similarly inclined friends, including poet John Ashbery.

As Dery points out, Gorey gradually assumed “a pose that incorporated elements of the aesthete, the idler, the dandy, the wit, the connoisseur of gossip, and the puckish ironist, wryly amused by life’s absurdities, steeped in the aestheticism of Oscar Wilde and in the ennui-stricken social satire of the ‘20s and ‘30s English novelists such as Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett, both of whom like Wilde were gay.” And both of whom were decisive influences on Gorey.

O’Hara at this point in his life wasn’t yet the gay bon vivant he would become when he worked at the Museum of Modern Art but, as is obvious from the tastes he and Gorey shared, he was well on his way. Curioulsy, while they frequented many of the same New York circles, Gorey and O’Hara saw little of each other after Harvard.

It was at Harvard that Gorey began to assemble his public persona which came to include the large fur coats and a furry beard. This outward appearance screamed “eccentric” if not outright gay at a time when nonconformity could court danger. Dery notes that during his Harvard years some of his classmates were outed and expelled. One of them was so disgraced that he committed suicide. That doubtless affected Gorey’s outlook, but there were other factors as well.

Gorey was the quintessential loner. Of himself he once observed, “I feel other people exist in a way I don’t.” This was less a statement of fact than the declaration of a goal. While he could enjoy the company of others and was involved in several separate social circles (his ballet friends often being different from his art and literary friends such as Alison Lurie and Peter Neumeyer). He had few romantic relationships of any length. As Dery charts it, Gorey’s personal life was a series of crushes where sexual relations weren’t always achieved. He did, however, at a certain period in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s venture into the Bird Circuit, those gay bars in the 50s on Third Avenue with such names as the Blue Parrot, The Swan, and “The Faison d’Or” (aka the Golden Pheasant) that catered to well-heeled business-suited gentlemen. He was never so louche as to hit the bars in the West Village But he wasn’t always buttoned-up. I myself spotted him a few times at the Everard Baths.

As for his work, gayness was reflected rarely. One of the best examples is his cover drawing for “Redburn,” Herman Melville’s gayest novel, showing a group of older men at a dock cruising a younger one who has just come into view. It’s quite in keeping with this daring novel’s homoerotic contents.

“Redburn” was one of more than 50 covers Gorey created for Doubleday/Anchor. He later moved on to Bobbs-Merrill and Looking Glass Library before going freelance, creating his own entirely individual works at the same time. All told he illustrated more than 300 books — some he loved like Melville’s, others he was less enthusiastic about, like Henry James’. Gorey didn’t care for James’ penchant for explaining his character’s inner thoughts in exhaustive detail.

Conventional sentiment played no role in Gorey’s work even when children were involved — perhaps a reflection of his own childhood. Gorey’s parents divorced in 1936 when he was 11 years old, then remarried in 1952 when he was 27. Abandonment and betrayal are perpetual Gorey themes. No standard expression of distress was attached to them — just violence as brought starkly into relief in “The Gashlicrumb Tinies,” a satirical alphabetical guide that begins, “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs. B is for Basil assaulted by Bears.” Its spirit well recalls Oscar Wilde’s infamous remark that “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing.”

Convention minded adults were appalled by Gorey’s images of children in distress. But many children were delighted. That Gorey would link his oddly playful images to such dark ideas enraptured them and made him — quite inadvertently — as popular with the very young as the works of his friend Maurice Sendak, whose “Where The Wild Things Are” so insightfully explores the aggressive instincts of little boys.

But children had to compete for Gorey’s artistic interest with adults in such word-and-image mini-masterpieces as “The West Wing,” a neo-gothic jape described by Dery as consisting of “frozen moments in the Victorian-Edwardian Manner.” Of “The Unstrung Harp,” Graham Greene declared it was “the best novel ever written about a novelist and I ought to know!” But in Dery’s view, something is missing from the praise heaped on Gorey — an inistence by the mainstream on turning a blind eye to queer subtexts in his work and persona.”

For all his success, Gorey’s oeuvre includes one serious misstep: “The Loathsome Couple.” This is Gorey’s illustrated recreation of Britain’s infamous Moors murders. Between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, Ian Brady and Myra Hindley murdered five children between the ages of five and 17, four of whom were also sexually assaulted. Actor and playwright Emlyn Williams (“Night Must Fall”) wrote a book about it entitled “Beyond Belief,” and Gordon Burn in his novel “Alma” noted the tape recordings the killers made of their crimes that included, in once instance, the voice of pop singer Alma Cogan, heard amidst a child’s agonized screaming, singing “The Little Drummer Boy.” That was a subtle reference. Gorey was for once not subtle at all, and “The Loathsome Couple” had no room for camp or any other mode of amusement. Gorey’s work here is rather a surprise in light of his declaration that he could barely read much of the Marquis de Sade’s “120 Days of Sodom,” so appalled was he by its contents.

A far happier creative occasion arrived in 1977 when director Dennis Rosa asked him to design the sets and costumes for a production of “Dracula.” Frank Langella was the nominal star of this production, playing the Count with the romantic suavity that was his specialty. But from the moment the curtain rose it was clear that the show’s real star was Edward Gorey. The audience burst into applause at the sight of Gorey designs served to them in life-sized portions. As the story had inhabited Gorey’s imagination for so long, designing “Dracula” was doubtless one of the great personal as well as artistic triumphs of his life. Sadly, he was never offered the chance to design another project like it, though his visual imaginativeness was not altogether blocked from wider popular view. The drawings he created for the PBS “Mystery” series were animated and served as its visual introduction, bringing him new fans.

On a less felicitous note for Gorey is what Dery terms “the last of his crushes” — a young man named Tom Fitzharris who may not have had sexual relations with Gorey (“as far as we know,” Dery notes slyly) but was a fellow ballet enthusiast. Gorey famously attended every performance by the New York City Ballet. So worshipful was he of its impresario George Balanchine that when the great man retired Gorey left New York for Cape Cod — having in his view no further reason to stay in the city. As for Fitzharris, the apex of their relationship was not ballet but film, for they both adored “I Know Where I’m Going!,” Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s 1945 Scotland-set romance. Gorey was, of course, more than passingly familiar with Powell and Pressburger’s ballet world masterpiece “The Red Shoes” (1948), but it was the earlier film set in the Scottish Hebrides that won his heart and Fitzharris’ too. The two embarked on a trip to see the places the film was set in, but in the middle of that trip their relationship suddenly fell apart. Fitzharris returned home and Gorey continued the journey on his own. What happened between them may never be known.

What is known is that Gorey’s fame and influence continued well into in his last years, even going so far as to include a Gorey appearance in a music video for Nine Inch Nails. As he approached death — the subject in many ways dearest to his heart — Gorey noted, “I’m the opposite of a hypochondriac… I’m not entirely enamored of the idea of living forever.”

But Edward Gorey will live forever in the hearts and minds of those of us who love “Buffy The Vampire Slayer” as much as he did, and in the works of film and literary artists as diverse as Tim Burton, Wes Anderson, and Dennis Cooper.

“I may not live forever but I feel perfectly fine all the time, Gorey said toward he close of his life.

It should be noted that he left his estate to the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust, which he established for the welfare of all living creatures including not only cats, dogs, whales, and birds, but also bats, insects, and invertebrates.

Surely that fully covers the “or something” that was Edward Gorey.

BORN TO BE POSTHUMOUS: THE ECCENTRIC LIFE AND MYSTERIOUS GENIUS OF EDWARD GOREY | By Mark Dery | William Collins | $34.99 | 512 pages