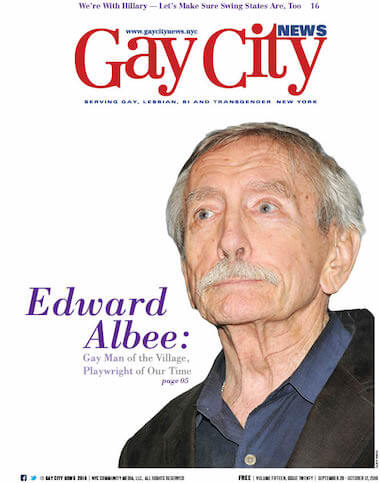

Edward Albee, 1928-2016. | DONNA ACETO

BY ANDY HUMM | The artistic achievement of Edward Albee was celebrated and chronicled in lengthy obituaries at his September 16 death at age 88 after a short illness. He was far and away America’s greatest living playwright, and it is hard to say who deserves that title now.

And while his openness about being gay and his early Greenwich Village years have certainly been noted, these factors were arguably the source of much of his genius, something not widely acknowledged. It may be that the significance of both are difficult to appreciate in an age when being out and gay is more and more common even in adolescence and when the Village has become an enclave for the rich — rather than a place where an emerging but still struggling artist could go to find himself.

Albee said he knew he was gay when he was eight years old and became sexually active at 12. When anyone expressed surprise at his sexual precociousness, he said — as he did on “Gay USA” in a 2005 interview with Ann Northrop and me — “I was going to an all-boys prep school. C’mon! I was just doing what was natural.”

His consciousness of being different in the late 1930s and early ‘40s intensified his contempt for his wealthy adoptive parents, Reed and Frances Albee, whose “morality and bigotry” he “hated.” He ran away from home in Larchmont when he was 12 — and was of course thwarted — but left for good and for Greenwich Village when he was 18.

“There’s a large distance between Larchmont and New York City,” he said on PBS’ “Theatre Talk” in 2007. “It is 20 miles, but it might as well be 30 million miles.”

An early relationship with the composer William Flanagan led to Albee’s social introduction to such heady gay company as composers Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and Ned Rorem.

Of Village life in those days, he said, “Nothing cost anything. There were so many interesting people to learn from. I just sat around and absorbed a great deal of stuff. I was learning all the time.” (Learning was something he was unable to do at Trinity College in Hartford, where he was forced out for refusing to go to chapel.) “I remember the Village when it was a real Village,” he told me in an interview for VillageCare’s annual “Legends of the Village” calendar.

Albee lived at 238 West Fourth Street “with seven or eight of my closest friends,” he said in the ’07 “Theatre Talk” interview, who were told to “sleep fast, we need the bed!” And he loved the Village: “I was getting to see the most wonderful theater imaginable — Beckett, Brecht, and Pirandello.”

Albee’s early writing consisted of what he said were bad poems and novels.

“I became fed up with everything, including myself,” he recalled.

While some describe his early Village years as fallow, he said, “I educated myself in life and the arts for 10 years and then wrote ‘Zoo Story,’” his breakthrough one-act play, written in two-and-a-half weeks in 1958 at age 30. The play was first produced in 1959, in German, on a Berlin double bill with Samuel Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape.” A year later, the two plays were produced in English at the Village’s Provincetown Playhouse and enjoyed a 14-month run that established him as a playwright and opened the door to his smash hit “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” on Broadway in 1962. The title of the play was a scrawl he saw written in soap on a mirror at a bar he frequented in 1954 at 139 West 10th Street that later became the gay bar Ninth Circle.

Albee was one of the most uncompromising American artists of all time. He was a playwright through and through, only allowing three films to be made of his plays — “Woolf” with Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton and directed by Mike Nichols in 1966, “A Delicate Balance” with Katharine Hepburn, Paul Scofield, and Kate Reid and directed by Tony Richardson, a gay man, in 1973, and “The Ballad of the Sad Café,” starring Vanessa Redgrave and Keith Carradine and directed by Simon Callow, also a gay man, in 1991.

Film producers balked at putting his plays on the screen because Albee insisted that not one word of what he wrote be changed for a film. And unlike esteemed playwrights such as Harold Pinter, Albee did not do screenplays. (Some productions of Albee’s plays, such as “Zoo Story” and “All Over,” were videotaped for TV.)

Despite his fierce, uncompromising reputation, Albee was also famous for nurturing young talents from a variety of the arts from the windfall profits of “Woolf” through the New Playwrights Unit Workshop (that “produced 110 new American plays,” he told me) and the Edward F. Albee Foundation. (“Why should I let the IRS have all that money?,” he would say.) The foundation runs the William Flanagan Memorial Creative Persons Center (named for his early lover but better known as the Barn) in Montauk “as a residence for writers and visual artists,” according to its website.

Albee was emphatic about not reading gay themes into his plays where he said he wrote none.

“There is no homosexuality in ‘The Zoo Story,’” he said referring to the relationship between Peter and Jerry and their fateful meeting across class lines in Central Park — though I will never forget Jerry’s line “I was an h-o-m-o-s-e-x-u-a-l,” which I first heard when the play was performed at my Catholic high school on Long Island, Chaminade, before the entire student body in 1969. I almost fell out of my seat.

Albee also forbade all-male productions of “Woolf,” simply reminding everyone that he wrote a play about two heterosexual couples, not two gay ones.

In 1961, the New York Times chief critic Harold Taubman wrote a homophobic piece — before that word was invented — saying that in emerging plays by gay writers the “unpleasant female of the species is exaggerated into a fantastically consuming monster or an incredibly pathetic drab” — and called such work “unhealthy.”

Critic Robert Brustein attacked “Zoo Story” for its “masochistic-homosexual perfume.”

Novelist Philip Roth skewered Albee’s “Tiny Alice” for its “ghastly pansy rhetoric.”

And Stanley Kauffman of the Times famously wrote a column in 1966 on “Homosexual Drama and Its Disguises,” chastising gay playwrights for creating distorted heterosexual couples that he insisted were really gay.

It was a perilous environment, and Albee later suffered exile from being produced in New York after critical and commercial failures such as “The Lady from Dubuque” (1980) and “The Man Who Had Three Arms” (1982) before re-emerging here with “Three Tall Women” in 1991 — earning him his fourth Pulitzer Prize if you count (and Albee did) the one awarded by its drama committee in 1962 but not approved by the full Pulitzer panel.

In “The Goat, or Who is Sylvia?” in 2002, Albee really cut loose, writing about a married man’s affair with a goat and exchanging a kiss with his gay son. It won him his second Tony for Best Play. He was also condemned for it.

“Clearly I was onto something!” he told us at “Gay USA.”

Yes, his integrity cost him. But as he said on “Gay USA” in 2005, “It would be wonderful to reach a larger audience. But life is too short. I would rather reach a smaller audience” — and say exactly what he wanted to say.

Albee had a rich gay life from the “fun” of recreational sex to a relationship with Terrence McNally in the 1950s to his 35-year relationship with sculptor Jonathan Thomas, who died in 2005. Albee gave up his 15-year stint teaching at the University of Houston to care for Thomas as he died of bladder cancer. (He also gave up drinking when he moved to a loft on Harrison Street in Tribeca that required him to operate the old-fashioned elevator — dangerous when under the influence.)

Albee frequently said, “We get the government we deserve.” That sounded harsh, especially given all the wealthy forces that average people are up against. But what I took it to mean is that we either have to engage in self-governance on a day-in-day-out basis or we will be saddled with the government that reactionary forces want to impose on us. He once said facetiously that the theme of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” is that “the ideals of the American Revolution are dead.” He was serious when he said that the characters of the battling couple, George and Martha, were named for our first First Family.

In our 2005 interview on “Gay USA,” he said, “Republicans are out to destroy the New Deal and destroy democracy.”

Albee felt that they had succeeded in part by “telling the working class that they’re middle class. The middle class is more reactionary.”

“Woolf” is being revived in London with Imelda Staunton and Conleth Hill this coming spring. Veteran Guardian critic Michael Billington wrote, “With America currently engaged in its own form of post-truth politics, now seems the perfect time to revive Albee’s enduring masterpiece about the danger of living in a world of illusions.”

When we spoke to Albee on Thanksgiving Day in 2005 on “Gay USA,” I asked what he was thankful for. He said, “We’re fortunate to still live in a democracy, fortunate we are still permitted to vote.”

Let’s hope we can keep our democracy without him, but his unsparing voice will be missed.