Kids today!

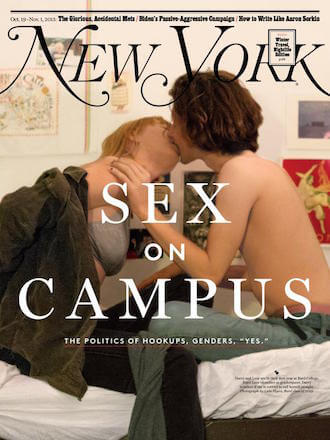

If New York magazine’s recent cover story, “Sex on Campus,” is even remotely accurate — and I have no doubt that it is — today’s college students’ sexuality is all over the map. They’re all talking about it, some are doing it, and some have the courage to say they’re just not all that into it. I picked up the issue expecting to find a mixed bag: a lot of attention to what’s now widely known as affirmative consent (“Yes means yes”), some prurience (the piece is lavishly illustrated with photos of youngsters in various states of undress), and more than a little handwringing — glib, anxiety-ridden, faux-urgent warnings about civilization’s decline.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. The story is actually a series of articles by a variety of writers, all of whom take fresh looks at the complicated terrain of youthful sex. It has more than a few surprises, such as:

College students in 2015 are actually having less sex than their parents did at that age. I find this shocking.

Facebook offers 58 different categories of self-defined sexual and gender expression in the user’s profile section, a fact described as “much-hyped” in the article but that was still news to me.

“On average, women have four drinks before a hookup and men have six.” What does this say about men’s and women’s differing need to get blotto before taking their clothes off?

I’m focusing here on only one section, “Identity-Free Identity Politics: A Report from the Agender, Aromantic, Asexual Front Line.” The reporter, Tim Murphy, begins with a lesson in contemporary semantics: “‘Currently, I say that I am agender. I’m removing myself from the social construct of gender,’ says Mars Marson, a 21-year-old NYU film major with a thatch of short black hair…. Of the seven students gathered at the Queer Union [at NYU], five prefer the singular they, meant to denote the kind of post-gender self-identification Marson describes.”

Media Circus

Being grammatically hung-up, I initially cringed at the idea of “the singular they,” but I have to admit that it solves the problem of having to gender every sentence when the subject of the sentence doesn’t want to be gendered in a binary, he or she way. And while I applaud young Mars’ effort to self-liberate, being agender doesn’t remove them from the social construct of gender at all because their self-identification is itself the product of social construction.

Say whaaa? Contemporary sex and gender studies rest on the foundation that sex is biological, and gender is cultural. “Marson was born a girl biologically,” Murphy writes, “and came out as a lesbian in high school. But NYU was a revelation — a place to explore transgenderism and then reject it. ‘I don’t feel connected to the word transgender because it feels more resonant with binary trans people.’” Murphy goes on to point out that folks like Marson aren’t identifying with “the middle of the path” either. “‘I think “in the middle’ still puts male and female as the be-all-and-end-all,’ says Thomas Rabuano… ‘I like to think of it as outside.’ Everyone in the group mm-hmmms approval and snaps their fingers in accord.” (Snapping fingers may be the new applause, but it’s not so new after all: it’s exactly what happens in the episode of “The Lucy Show” in the ‘60s when Lucy and Viv go to the beatnik café.) But what Marson and Rabuano and the mm-hmmming and finger-snapping others aren’t appreciating is that one can never be outside of social construction — that the cultural forces that produce male and female also produce them. They can no more stand outside the continuum of gender than they can stand outside of this galaxy. If the constructs male and female are socially constructed illusions, so is the sense of being outside the spectrum.

A third person describes themself as “an agender demi-girl with connection to the female binary gender.” I blame Judith Butler.

Murphy concludes his piece with a touching reminder of how difficult it is to figure out who you are: “The complicated language, too, can function as a layer of protection. ‘You can get very comfortable here at the LGBT center and get used to people asking your pronouns and everyone knowing you’re queer,’ says Xena Becker, 20, a sophomore from Evanston, Illinois, who identifies as a bisexual queer ciswoman. ‘But it’s still really lonely, hard, and confusing a lot of the time. Just because there are more words doesn’t mean that the feelings are easier.’”

Like a selfish trick, Roland Emmerich’s “Stonewall” came and went so fast that it may as well not have shown up in the first place. I didn’t see it. So I can’t comment on it. I’ll leave that to the exceedingly capable openly gay critic Alonso Duralde, who writes: “‘Stonewall’ somehow manages to be simultaneously bloated and anemic, overstuffed and underpopulated. It’s a story about a true historical event that spends way too much time on its fictional lead character [a cute blond boy from the Midwest]; the tone is so erratic and artificial that it wouldn’t feel surprising if the movie suddenly became a musical. And as the film gets duller and duller, you find yourself wishing these characters would break into song, just for variety's sake… It’s as if ‘Selma’ had focused on a fictional white liberal character instead of Martin Luther King, Jr.”

Yikes!

Follow @EdSikov on Twitter and Facebook.