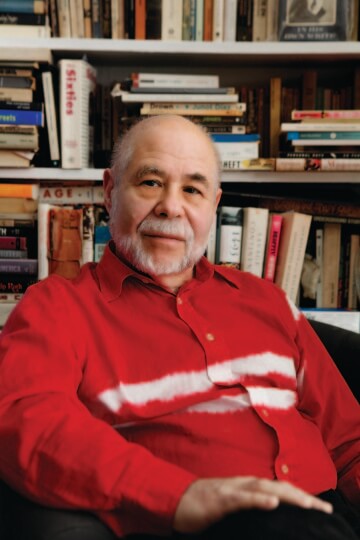

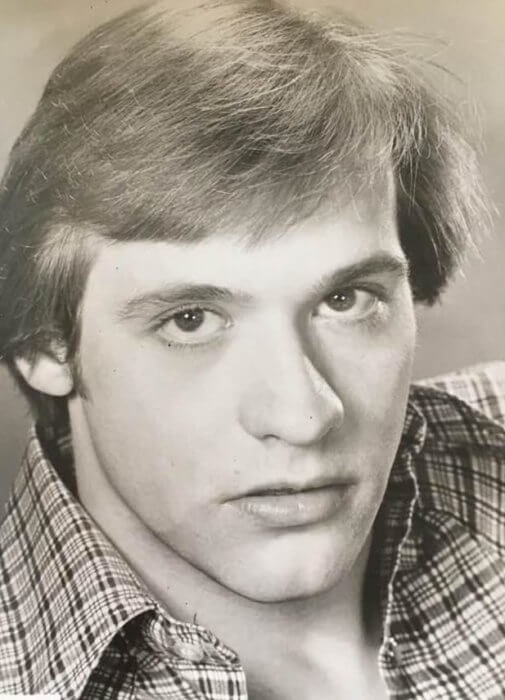

Dean P. Wrzeszcz, a writer, actor, and singer whose work life included several years as a copy editor at Gay City News — where he was also a story contributor — died on April 3 after more than a week of suffering symptoms of COVID-19.

Born October 11, 1957 in Erie, Pennsylvania, Dean, 62, was the son of the late Aloysius Wrzeszcz and Irene Wawrzyniak Wrzeszcz and was raised in Erie with his younger siblings, Victoria and Richard.

A high school honor student in English who played saxophone and clarinet, Dean went on to study voice, ballet, tap, and jazz dancing at Erie’s Mercyhurst University. In the Erie theater scene, Dean acted in “Fiddler On The Roof” and “A Streetcar Named Desire,” among other productions. From there, he took a job as stage manager with the Ohio Kenley Players summer stock company in Warren, where he worked with famed actors that included Henry Winkler, Harvey Korman, and Carol Lawrence.

But from the time of his high school senior trip to New York, it was clear that’s where he would end up. With high expectations, Dean, like so many gay men in those years and since, moved to the city in 1978, where he won a number of roles in Off-Broadway productions and on television.

But Budd Isaacson, who dated Dean for about a year after Dean’s arrival in New York and enjoyed a 42-year friendship with him, recalls that more than auditioning, he was focused on learning the craft of acting. He studied first with actor William Hickey at the HB Studio in the West Village and later at the William Esper Studio on West 37th Street.

Dean’s insistence on learning the art of acting speaks to a perfectionism that imbued all his endeavors.

Decades later, in 2012, Dean played the bishop in a New York City staged reading of playwright Tony Adams’ “A Letter from the Bishop,” an intriguing drama about homophobia and closetedness in the Catholic Church.

“I was amazed at the way Dean played the part of the bishop,” Adams recalled this week. “I say ‘play’ rather than just ‘read’ because he had the part memorized even though the event was a reading, not a performance. The theater was packed but you could have heard a pin drop during Dean’s scene. The dismissive acerbic blessing he brandished at the end of that scene elicited a huge laugh and applause. That comic flourish would not have worked had he not been so successful in finding and delivering the full personality of the homophobic bishop. He made the play work.”

Dean’s pursuit of acting in his earliest years in New York, however, was “derailed” according to Isaacson by a doctor in the early 1980s telling him, “You probably have pre-AIDS and maybe six months to live.”

“His self-confidence as an actor went away,” Isaacson recalled, and Dean soon moved to San Francisco, which he thought made for “a better place to die.”

Dean didn’t die in San Francisco; instead he found employment at a law firm in document services, where his skills at writing caught the attention of attorneys who came to rely on him to wordsmith their work. When he returned to New York in the late ‘80s, Dean continued his work in legal document support for more than 15 years, again as a staff member valued by senior attorneys, according to Isaacson.

After leaving his final law firm employer in 2005, Dean turned his attention to writing, taking classes, participating in peer writing groups, and publishing in a wide array of venues.

For The Philadelphia Inquirer, he wrote about his happy discovery of heirloom tomatoes on a return visit to his sister Vicky’s home in Erie.

In addition to eagle-eye copy editing for Gay City News, Dean wrote on a wide variety of topics. Embedded in a grueling, weeklong gay men’s fitness boot camp, he wrote “Boot Licked.”

A review of Michael Musto’s “Fork on the Left, Knife in the Back” prompted the Village Voice veteran to brag, “Gay City News Gives Me A Huge Thumbs Up.”

And Dean’s final contribution to Gay City News, in 2018, “Out For the Holidays,” described his coming out to his father in the 1980s against the persistent pleadings of his mother and sister.

In all of Dean’s writing, he combined a concise, economical style with keenly observed details — and, at times, a wicked satirical tone —a skill that probably contributed to his appeal as an actor as well.

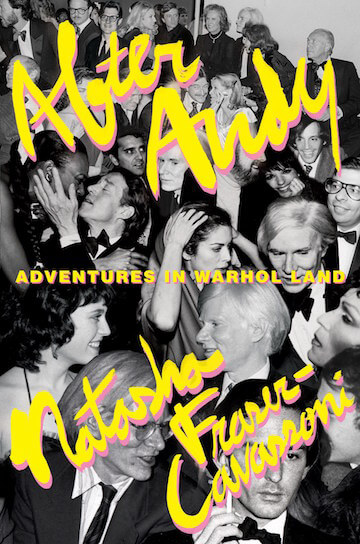

In 2016, Dean published “My Dinner With Andy,” a memory piece about an evening decades before that he began with Liz Eden — the transgender ex-partner of the character Al Pacino portrayed so memorably in “Dog Day Afternoon” — before meeting and spending time with fashion designer Halston, Studio 54 co-owner Steve Rubell, and the one and only Andy Warhol.

When, in 2017, he appeared at the Trumpet Fiction series that formerly ran at the East Village’s KGB Bar, Dean didn’t read the piece so much as he acted it, taking on the voices and mannerisms of each of its legendary characters.

Dean was also a singer, and rewarded this writer with a tape of his take on Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah,” John Lennon’s “Imagine,” and the spine-tingling “Bad Things,” the theme song from HBO’s utterly queer vampire series “True Blood.”

In recent years, Dean’s friend Court Stroud, a fellow writing group member, recalled, Dean put in earnest time at his West 45th Street apartment building’s gym keeping in top shape. He also became something of the “mayor” of the complex.

When news of Dean’s death emerged, a resident of the building, Michael Sage, wrote on Facebook, “I will always remember our epic ‘Hard Rock Monopoly’ game by the fireplace at Gotham West… Always made me laugh about anything. The consummate Court Jester has been taken from us. I’m absolutely gutted.”

Stroud recalled Dean’s love of his apartment on West 45th and said that despite the tragic circumstances of his death, Dean “went out on a high note.”

Stroud was the last to see Dean alive, having done a grocery run for him on April 2. Dean had trouble getting to the door when Stroud arrived, explaining that hours earlier his legs had gone out from under him. Stroud tried in vain to persuade him to go an emergency room, but said, “Dean was very willful.”

Dean’s sister, Vicky, recalled days earlier also running into a brick wall in pressing him to go to an ER. Like Stroud, she acknowledged his stubborn streak. As children, Dean, two and half years older than twins Vicky and Richard, would organize hilarious games where the three would play records and get up and sing and dance, always trying to make each other laugh.

But, she said, “He was the big brother. He was obstinate.”

Brother and sister spoke on March 29, when Dean told Vicky, “I think I have it.”

Dean then launched into an angry tirade against Donald Trump’s false promises from earlier in the year that coronavirus would be no big deal in the US. His fierce anger over his illness was something Stroud mentioned, as well.

“He had so much anger that he was getting mean, and I told him I had to hang up,” Vicky said.

But the text Dean sent her the next day did not necessarily reflect the obstinacy of a stubborn man, but rather the thoughtful-even-while-despairing confusion of a sick man in a city and a country that were holding out no real promise they could heal the sick.

He wrote, in part, “Mean? I’m angry. I’m scared. Mean? No, I’m not mean. You’re talking to someone whose body is envied by men half his age. I can breath on my own. My immune system is working fine. Becoming exposed to the virus in New York City is practically guaranteed. How sick one gets is different. I have mild to moderate symptoms. Only the hacking dry cough scared me for a few days into thinking I could get pneumonia. But I know I’d be more sick if I sat in an ER for six hours. One big difference all of us can do is keep our germs/ droplets to ourselves. As much as I hate the guy in the White House, I feel it’s my job to know every fucked up thing he does. Lying around taking my drugs (the ones I have taken for 35 years!!), sleeping, watching TV, and isolating while trying not to freak out are all part of taking care of myself. Protecting others by staying home, and I’m not doing anything physical I’m not ready to do. I wash pajamas and towels and sweaty sheets and pillowcases, and disinfect refrigerator handles and doorknobs. I get exhausted from that. Physically and psychologically. I have tried buying a thermometer for weeks. No drug store had any. I got one ordered and won’t receive one until April 11 from Amazon.”

In addition to sister Vicky Wrzeszcz and her wife Sheryl Carpenter of Erie and brother Richard Wrzeszcz and his partner Christine of Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, Dean is survived by half-brothers Samuel Randazzo and John Wrzeszcz and half-sister Joanne Fritz. Among the many friends he leaves behind are Isaacson of Riverdale, Stroud and his husband Eddie Sarfaty of Manhattan, Adams of Fort Lauderdale, H. Richard Quadracci of Hollywood, Florida, and the Reverend David McFarland Nuttle and his husband Tim Nuttle of Pittsburgh.

A memorial will be planned at a later date.