As State Assemblymember Deborah Glick and Senator Brad Hoylman look on at a November 20 town hall, Mayor Bill de Blasio pledges the city’s cooperation in resisting Trump administration moves against communities from immigrants to LGBT New Yorkers. | ZACH WILLIAMS

Addressing a crowd of several hundred people who had gathered at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual & Transgender Community Center to wrestle with how to respond to Donald Trump winning the White House and continued Republican control of Congress, Mayor Bill de Blasio had a simple message — unity.

“Those of us on the left have to be unified,” the mayor said at the November 20 town hall meeting. “This is how we fight back. We fight back by gathering in the same room in solidarity.”

The mayor carried the same message to an even larger crowd at Cooper Union’s Great Hall the next day saying, “I want to thank everyone for being here because this is a moment when New York City needs to stand tall. We need to stand together.”

With incomplete record of unifying “two cities,” mayor bets new president is apt foil

The appearances serve a dual purpose. They calm a city that is worried about Trump’s threats to deport immigrants, register and track Muslims, and end Obamacare, and they continue de Blasio’s 2017 reelection campaign with the mayor promising that the city will protect these groups from the new administration in Washington. At its heart, it is an anti-Trump message.

“I think that’s the theme of the campaign,” said Ken Sherrill, a professor emeritus of political science at Hunter College.

In 2013, de Blasio ran a populist “tale of two cities” campaign. He talked about creating pre-K for all, which he has done, and enacting paid sick leave at many employers, which has also been done. The city has seen job growth, though many of those jobs are low-wage. While the mayor will claim progress on building affordable housing, any opponent would likely dispute that.

Economics resonated with voters then and now.

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders used such a message during his failed effort to win the Democratic nomination for president. Trump also ran on an economic platform, railing against perceived unfair trade deals and lost jobs. Trump promised to bring back industries that have struggled, such as coal and steel manufacturing.

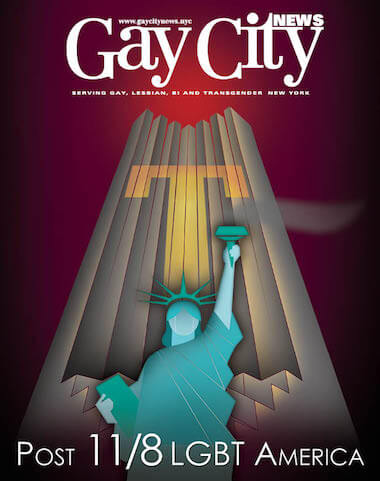

COVER DESIGN BY MICHAEL SHIREY

“Old fashioned, New Deal, Fair Deal politics sure has been doing well recently, and that’s a politics that downplays identity, with the exception of Trump playing up race,” Sherrill said.

The mayor has shifted. At least for the moment, de Blasio is using a theme that looks more like Hillary Clinton’s failed campaign for president.

“It’s very interesting because in some ways the strategy mirrors the Clinton message for the last election,” Sherrill said. “He insulted this group, he insulted that group, we’re better than that.”

While Clinton also talked about economic issues, she played in identity politics and presented herself as the only alternative to Trump, who was “unfit” for the presidency.

“It may be insufficient,” Sherrill said. “All in all, it helps [de Blasio]. I think that Donald Trump is the perfect foil, but the one potential downside is that somebody will run a 2013 Bill de Blasio campaign and he will have a hard time defending against that.”

The mayor’s greatest threat comes from a Democrat challenging him in next year’s primary. While he can claim successes, it may be that there are enough Democratic voters who are upset by the city’s more visible homeless population, by slow job growth, and by hearing stories about housing problems to deliver a loss to de Blasio.

“The thing about affordable housing, or unaffordable housing, is that most people have not had to move because they could not afford the rent, but it may be that enough people may know someone who has that they worry it could happen to them,” Sherrill said. “The strategy of someone running against him would be to say that solving a tale of two cities is a lot of bunk, working people still can’t find a place to live in the city.”

Some on the left would certainly approve of de Blasio’s promise to resist any efforts by the Trump administration to deport immigrants, but those voters, by definition, would not face deportation themselves and that message may be less powerful among them.

Bradley Tusk, a former Bloomberg administration official, made recent public efforts to recruit a candidate to oppose de Blasio next year. A Republican would probably not perform well in 2017 in a city in which 78 percent of voters went for Clinton and just 18 percent backed Trump. A Republican candidate for mayor would struggle if Republicans in Washington actually implement some of their controversial proposals. Tusk did not respond to a message seeking comment.

The mayor may yet return to his economic populist theme of four years ago by arguing that his administration has made progress on the issues he campaigned on. That would turn the race into a referendum on his performance, something the mayor and his campaign may choose to avoid given that the city has not unambiguously improved. Running against Trump and Washington might be his only choice.

“What de Blasio appears to be doing this time, most charitably, is to say we’ve made substantial progress on the issues we talked about four years ago,” Sherrill said. “The question is whether the claim is credible to the average voter.”