David Carter, an historian, author, and LGBTQ activist whose 2004 book “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution” remains, more than 15 years later, the definitive account of the fateful events in Greenwich Village in late June of 1969, died May 1 in his West Village home.

Carter, who was 67, had a history of heart trouble, and his older brother William said he was told the likely cause of death was a heart attack.

Carter was born and raised in Jesup, in southeastern Georgia, which at the time his book came out he described to Gay City News’ Duncan Osborne as “a small, conservative town.” William, his brother, was 11 years older than he and on his way to becoming a university professor and scholar of Marcel Proust.

“He would bring in the larger, outside world to me,” Carter said of William’s influence on his young life. “Whenever he came home, he would bring the latest Broadway show albums or art books. I grew up with Marcel Proust in the house.”

Meticulously researched 2004 book set high standard for documenting LGBTQ history

William last week recalled being a graduate student at the University of Georgia at Athens when a teenaged David visited him. The Metropolitan Opera was in Atlanta that weekend, and the brothers attended a performance of “Parsifal.”

“This was the beginning, I believe, of David’s love for classical music,” William told the newspaper.

Carter himself attended Emory University in Atlanta, where he majored in Religion and French, spending his junior year at the Sorbonne in Paris. He earned a master’s degree in South Asian Studies at the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

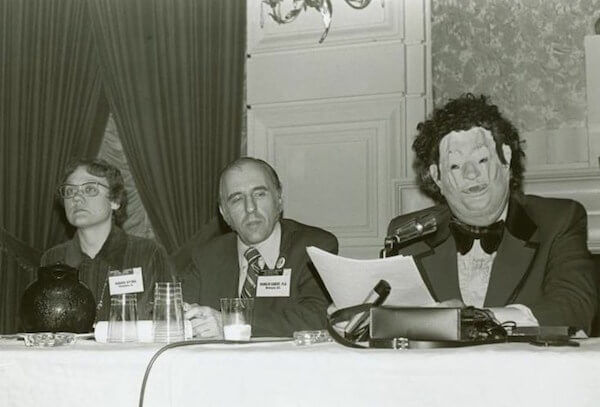

It was during his time in Madison, Carter recalled last year, that he became active in the gay rights movement, organizing a dance to raise money for the fight against Anita Bryant’s 1977 campaign to overturn Dade County, Florida’s sexual orientation nondiscrimination ordinance. The following year, he was the co-founder of a group formed to beat back a similar repeal effort in Madison. That group was the launch pad for the successful effort to make Wisconsin the first state in the nation to enact a ban on sexual orientation discrimination in 1982.

Moving to New York City in 1985, Carter worked as an editor at Chelsea House Publishers, which produced young adult multicultural books. He wrote biographies of the artist Salvador Dalí and the philosopher and author George Santayana for that market and also originated two series of young adult books for Chelsea House — “Issues in Gay and Lesbian Life” and “Lives of Notable Gay Men and Lesbians.”

While still in Madison, Carter had met Allen Ginsberg when the famed Beat poet and author did a reading at the university. Shortly before Ginsberg’s death in 1997, Carter began working with him on editing a book of interviews Ginsberg had given between 1958 and 1996. Carter completed the book after Ginsberg’s death, and “Spontaneous Mind” was published in 2001.

Carter also worked with Pete Townshend, the guitarist, singer, and songwriter with The Who, directing a film about Meher Baba, the late Indian spiritual master in whom the two men shared an interest.

Carter’s most important work, however, began in 1994 during the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

Recalling the wide array of panel discussions and other events held that year in commemoration, Carter told Gay City News, “I figured people would be coming out of the woodwork and I tried to do everything I could to track down information. I tried to attend every event that I could.”

He began gathering documents and reaching out to participants in the several nights of civil disobedience for interviews. One of the innovations Carter brought to his examination of Stonewall was the use of a map of the Sheridan Square area where the bar was located. In his interviews, he asked the June 1969 participants to point out on the map where they were, what they saw, and when specific events happened.

“Bit by bit I was building up a database,” Carter recalled.

The result was nearly a minute-by-minute account of the riot, and he was able to see where witnesses agreed in their accounts.

“It was very painstaking, but very satisfying,” Carter told Gay City News. “I put them side by side and studied them.”

The meticulousness of Carter’s work is particularly important given the competing claims about who played key roles in the militant response to the NYPD’s raid on the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969 — white gay men, the transgender community, people of color, lesbians. He found evidence to support all of these claims.

“One thing that is rather beautiful about it is the action encompassed everyone,” he said. “It was the entire community. The way I see it, there is plenty of credit to go around.”

In an essay published in last year’s Gay City News Pride issue, Carter wrote, “My conclusion is that most of the crowd in the vanguard on the Uprising’s first night were white men, though Marsha P. Johnson and Zazu Nova, both transgender, were Black, and there were some Black and Latinx youth among the homeless street youth who were the first to lead the charge against the police.”

He added, “My research concluded that the two most important groups in the vanguard on the first night — beyond the butch lesbian who resisted arrest and probably had the greatest impact — were homeless gay street youth and transgender people, including Marsha P. Johnson and Zazu Nova, both trans women, and Jackie Hormona, a member of the gay street youth. Most of the gay street youth were more or less feminine — or, in today’s parlance, non-gender conforming — young men, not transgender, and the majority were white.”

But he also mentioned a cautionary coda to this summary, writing, “While this vanguard played the key role in escalating the conflict, it is important to not let their pride of place throw others who fought into the shadows. When I recently mentioned the two groups in the vanguard to [Stonewall participant] Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt, he said, ‘But almost immediately — within a few moments — everyone else was jumping in.’”

Beyond the 145 interviews Carter did with 91 people, 70 of whom witnessed the riots, he found roughly 15 written accounts from 1969, including police reports, newspaper articles, and letters. Those too confirmed the consensus view that Carter’s witnesses had shaped.

“One of the things I heard over and over was there are very few written records from 1969 and they really disagree with each other,” Carter told Gay City News at the time his book was published. “What I found was an extraordinary degree of agreement among the written accounts. That gave me faith in them. They corroborated each other.”

“Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution” has been praised on many counts.

Ken Lustbader, an historic preservation consultant in New York who is a co-founder of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, said that Carter was a “trailblazer” in “understanding so early the importance of place in history.” Lustbader recalled Carter’s excitement at learning that Lustbader had found the original floor plans of the bar by searching the city Buildings Department archive. The layout of the bar and the geography of the West Village and the blocks immediately surrounding Sheridan Square and the bar were critical, he said, in shaping the crowd response to the police. Carter appreciated that, and his book brings readers into the action by effectively setting the riot’s physical scene.

Lustbader’s colleague Andrew S. Dolkart, a professor of Historic Preservation at Columbia University and the co-director of the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, echoed that assessment.

In describing the effort to have the Stonewall recognized on the National Park Service’s National Register of Historic Places in 1999 — the 3oth anniversary of the riots — Dolkart said of Carter, “He was the person who helped us understand that the reason why Stonewall was such a successful demonstration, as opposed to other bar raid responses, was the street pattern of Greenwich Village, which permitted demonstrators to be chased up one street and then double back to the Christopher Park area down another street. Also, the demonstrators understood the street layout, whereas the tactical police group, who were brought in from another area, did not.”

What was particularly impressive to both Dolkart and Lustbader was that Carter shared much of his research with the group seeking National Register recognition even though he had not yet published his book.

“He was so generous with his research,” Lustbader noted. “That spoke to his integrity… that he would allow the use of his research pre-book publication.”

Dolkart recalled of the 1999 effort, “We really could not have done such a complete job without him.”

The way that many people who knew Carter describe his commitment to LGBTQ history, it is not really surprising that he was willing to share his own research, before having received public credit for it, in the interest of preserving the community’s collective memory. Kevin Jennings, the CEO of Lambda Legal, met Carter about five years ago when the two were both working in the effort to establish an LGBTQ history museum in New York.

“He was always generous with his time,” Jennings recalled last week. “He was committed to making sure we got LGBTQ history right and that it was something that got passed along to the next generation.”

Getting it right is another key quality that people who knew Carter and care about LGBTQ history praise him for.

“So many myths have grown up about that night and I urge anyone who cares about our community’s history to read the book,” Jennings said of Carter’s “Stonewall.” “It was thoroughly and meticulously researched and is an enduring gift to our community. David was an old fashioned historian, with a refusal to deviate what could be proven… I think he felt that if we were going to be taken seriously as a community that we need to hold our historians to the same standards as we hold mainstream historians to.”

Jonathan Ned Katz, an historian who founded OutHistory.org, similarly praised Carter’s painstaking approach to writing “Stonewall.”

“I was greatly impressed with his book on Stonewall, and his desire to distinguish fact from rumor,” Katz told Gay City News last week. “David and I were both very interested in evidence. We were both investigators. There is investigative journalism, and there should be a category investigative history. Nobody had asked under FOIA the NYPD whether there were files on Stonewall. It was very exciting. They named four people arrested, including a woman.”

In 2010, Carter’s book was the basis for a PBS “American Experience” documentary “Stonewall Uprising,” directed by Katie Davis and David Heilbroner.

The depth of Carter’s understanding of the Stonewall riots became a decisive advantage a decade after the book’s publication when the successful push to have the area surrounding the bar designated a national monument began.

Lustbader recalled a 2015 meeting with the Interior Department, where advocates of the designation needed to convince federal officials that Stonewall was the right choice to become the first LGBTQ monument in the nation. When Carter made a five-minute presentation on the historical significance of the 1969 riots, Lustbader said, “There was not a dry eye in the room.” Carter’s presentation was the “linchpin of the decision” to move ahead, according to Lustbader. “It helped pave the way for the government to be confident that, ‘We have our ducks in order. We have great advocates.’” He added, “David was so engaging and thorough. His enthusiasm bled through.”

Lustbader commented on another of Carter’s qualities that others also saw in his.

“David was always gentle,” he recalled.

“He was a very caring person,” Katz said. “He called me when a gay artist had been thrown out of his apartment and he was trying to help him. David was very good-hearted.”

“He was a true gentleman,” Jennings said, adding that Carter also “had a great sense of humor.’

Jennings recalled organizing a panel discussion in which Carter was participating and telling him he would have three minutes to introduce himself. Carter response was, “Kevin, I’m from the South. We can’t clear our throat in three minutes.”

Eric Danzer was a close friend of Carter for more than 15 years, and he too described him as “a true gentleman,” but also “a passionate fighter.”

“There was a kindness, a sweetness about him,” Danzer said. “One of the coolest things about David was that despite the scholarly, professorial side of him, he could tell quirky jokes with the best of them. It was a sweet balance.

Several years ago, Carter held the Patrick Henry Fellowship at Washington College, an appointment that allowed him to continue his research and writing on a planned biography of gay right pioneer Frank Kameny, who in 1957 lost his federal government job as an astronomer because he was gay and went on to co-found the Washington, DC, chapter of the Mattachine Society. According to Danzer, Carter oversaw the work of five interns during his time at Washington College, helping them in their efforts to explore LGBTQ history.

Doing “service,” as Danzer characterized it, for young people interested in LGBTQ history was a constant in Carter’s life. Danzer recalled that right up to his death Carter was fielding phone calls from college and high students pursuing research interests. So long as the young people had done their basic homework on the topic, Carter was happy to give them his time and attention.

In recent years, Carter supported his historical work by doing technical writing for medical publications.

According to Danzer, Carter had been researching for his Kameny biography for 11 years. Both Katz and Jennings voiced the hope that the disposition of Carter’s papers will allow other historians to pick up from where he left off.

“I was really looking forward to reading his biography of Frank Kameny,” Jennings said with a note of sadness.

According to William Carter, David’s body was flown back to Jesup for a small funeral service due to the restrictions made necessary by the coronavirus outbreak. Memorial services in both Jesup and New York City will be planned once public health considerations allow for large gatherings.

David Carter is survived by his brother William C. Carter and sister-in-law Lynn, three nieces, Josephine Monmaney, Sarah Davis, and Susanna Carter, and five great nieces and great nephews, as well as by his long-time friend Eric Danzer.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.