Danny Garvin with his friend Martin Boyce at the White House with President and Mrs. Obama on June 30 of last year. | FACEBOOK.COM

Danny Garvin, who was a 20-year-old gay hippie when he arrived at the Stonewall Inn on the night of the famous June 1969 raid — just as the first club patrons who had been detained inside were being released by the police — died on December 9 at age 65. In addition to being a participant in the Stonewall Uprising, he was a longtime habitué of the club and contributed much to our understanding of that event as both a witness to that historic night and someone with intimate knowledge of the fabled night spot’s place in gay culture at the time.

Daniel Francis Garvin was born to Michael Joseph Garvin and Mary Theresa Kelly Garvin — both from County Mayo, Ireland — in New York City on March 1, 1949. He grew up in Inwood, the upper Manhattan neighborhood he recalled as “a big, middle-class immigrant neighborhood. Mostly Irish and Italian, and German Jews.”

Like all the boys in his neighborhood, he belonged to a gang, and his was called the Ramrods. Coming out was very difficult for Danny, both because of the sexual guilt passed on to him from his very Roman Catholic family and because he lacked any positive role models. “It was just older gentlemen in subway restrooms,” Danny explained to me, in interviews for my 2004 book “Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution.” “Even glimpses of what you would see in a movie… was always a super-effeminate gay male image. And I knew that wasn’t me.”

Gay man, invaluable source in documenting Stonewall Uprising, later asked a president to finish the “dance”

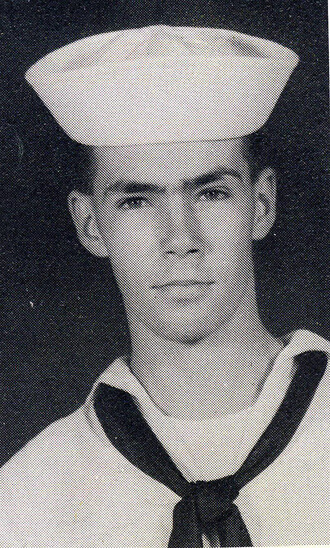

Danny’s mother died when he was quite young, and his father retired to Ireland when Danny was 17, but not before enlisting him in the Navy. Stationed in Brooklyn and working as a cook, he was in the early stages of coming out when some fellow sailors took him to the West Village bar Julius’. Danny didn’t at first realize it was a gay bar, and in any event did not find anyone his own age he could relate to.

As he continued his struggle with coming out, during a night of misadventures, the pressures all came together and threw him into a panic. While off the base, he learned about the death of a girl he had a crush on and proceeded to get drunk, left his identification in a liquor store, and slept too late to get back to his quarters on time. He then sought out the only gay man of his own age he knew, seeking support. But knowing Danny was both underage and AWOL, the friend told him to get lost.

Danny Garvin, while in served on a naval base in Brooklyn. | FACEBOOK.COM

In desperation, Danny made a half-hearted suicide attempt and then called a psychiatrist, who advised him to check himself into Bellevue Hospital. When the Navy was informed, he was transferred to St. Albans Naval Hospital in Queens. There, Danny faced a quandary: talking about his problems with coming out would get him a dishonorable discharge, which in that era would have made him unemployable. In the end, according to Danny, the Navy agreed to give him an honorable discharge on the condition he sign a document attesting that his psychological crisis had its roots in his mother’s death so that the military would not have to pay for his future medical care.

Discharged on St. Patrick’s Day, 1967, about two weeks after having turned 18, Danny decided to celebrate that night at Julius’. A friendly older man there asked him why he wasn’t at the new bar just opening around the corner on Christopher Street where all the young people were. Deciding to go check it out, Danny walked into the Stonewall Inn on its opening night. Like everyone else who frequented the Stonewall, it was the dancing there that impressed him the most in an era when gay bars generally did not allow dancing, since same-sex pairing up was against the law and drew police crackdowns.

“I walked in there and saw all these people dancing, and I had never seen so many men dancing in my life,” he said. “And I was like, in shock — thinking, this will never last!”

But on a subsequent visit to the Stonewall, Danny joined in the fun, when a friend arranged for him to be approached by a man he had confided he was attracted to. “I realized if I didn’t dance with this guy, we probably wouldn’t get it on together,” Danny recalled. “That was my first time I allowed myself to dance, to be part of gay life. To go ahead and kiss a man in public.”

Danny soon became a Stonewall regular, and in time he would date the bar’s main doorman, who was known as Blond Frankie. He also befriended a man named Francesco, who worked at the Stonewall’s coat check under the camp name Barbara Eden, who then played the title role in TV’s “I Dream of Jeannie.”

Around this time, Danny moved into what may have been New York’s first gay hippie commune, where he lived for two years. He recalled that while members of the commune and their friends often discussed women’s issues, the war in Vietnam, and other political questions, they never once had a conversation about the meaning of being gay in a profoundly anti-gay society. Danny became a regular pot smoker and started selling LSD at the Stonewall.

Late in the evening on the last Friday of June 1969, Danny passed on going to the Stonewall and headed further west on Christopher to a new club — named Danny’s — that was the new gay hot spot. There he bumped into an old flame, Keith Murdoch, at home from college, and the two headed back to Danny’s commune where they smoked grass and had sex. They decided to finish the night off by dancing at the Stonewall. As they walked up Seventh Avenue South toward Christopher in the very early morning hours of Saturday, June 28, they engaged in a heady conversation about the possibility that a revolution was coming in America. When they saw a crowd protesting outside the club, Danny’s first impression was that the revolution had just started.

His vivid memories of what he saw the first two nights of the Uprising add valuable, human detail to our knowledge of what took place. He witnessed, for example, the NYPD patrol wagon being assaulted by the crowd, gay men using an uprooted parking meter to try to break down the Stonewall’s doors so they could attack the police barricaded inside, and the chorus line gay men formed to mock the advancing line of police trying to clear the streets.

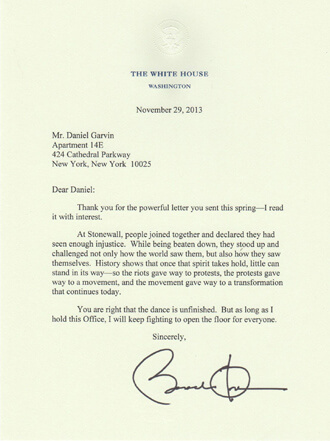

President Barack Obama’s response to Danny Garvin’s letter saying he had not yet had the chance at doing the “I Am A Completely Free Gay American Dance.” | FACEBOOK.COM

“I saw a bunch of guys on one side and the cops over there, and the cops with their feet spread apart and holding their billy clubs straight out,” Danny recalled. “And these queens all of a sudden rolled up their pants legs into knickers, and they stood right in front of the cops… and the cops just charged with the night sticks and started smacking them in the heads, hitting people, pulling them into the [police] car. . . . And for what? A kick line.”

Danny was outraged by the gross injustice he was witnessing, but as a pacifist hippie, he did not participate in any violence. But he did join the crowds of protesters resisting police efforts to clear the streets so that they could bring the Uprising to an end.

In the years after the Uprising, Danny’s life remained entwined with many key cultural moments in New York gay life. He marched in the earliest annual pride parades, then called Christopher Street Liberation Day marches, and was for a time roommates with Morty Manford, a leader in the Gay Activists Alliance. Danny played a role in Manford coming out to his parents, who went on to found PFLAG, now known as Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays. For a time, he ran with Andy Warhol’s circle, and he worked at the first gay bar with a back room, the Zoo. Danny lost the love of his life to AIDS and then, approximately a year and a half later, entered a friary in 1991 with the intention — for a time, at least — of becoming a priest.

Danny also became involved in the recovery movement. His friend Thom Hansen recalled Danny’s role in establishing a show of sobriety in the Pride March: “Danny decided to organize a group of us from AA — and we were many — into a group called Sober Together. I helped him — and it was incredible. By the second or third year in the early ‘80s, we were the largest contingent in the march.”

President Barack Obama’s 2013 inaugural speech, which invoked a tradition of civil rights advances from “Seneca Falls to Selma to Stonewall,” prompted Danny’s most prominent recognition as a gay man. He wrote to the president urging him to do even more. Noting that the Stonewall raid was caused by the simple desire gay people had to dance, Danny wrote, “You made me proud sir when you mentioned that significant part of my life, but it is a battle that is not over yet, and we still have a big fight on our hands. I still have not gotten to dance that dance I started 44 years ago. The big joyous ‘I Am A Completely Free Gay American Dance’ yet, and I so badly want to dance that dance before I meet my maker.”

The president responded, writing, “You are right that the dance is unfinished. But as long as I hold this Office, I will keep fighting to open the floor for everyone.”

Later, Danny received a second correspondence from Obama — an invitation to attend the June 30, 2014 White House reception celebrating LGBT Pride Month. In a follow-up phone call, the White House asked that he arrive early “because President Obama would like to have his picture taken with you.”

Whatever early problems Danny had about being gay, he came out to his family long ago and enjoyed warm relationships with all of them over the decades. One nephew recalled him as the favorite uncle and told me — with a mixture of pride and awe — how Danny always gave them tickets to Broadway shows as presents on their birthdays and at Christmas.

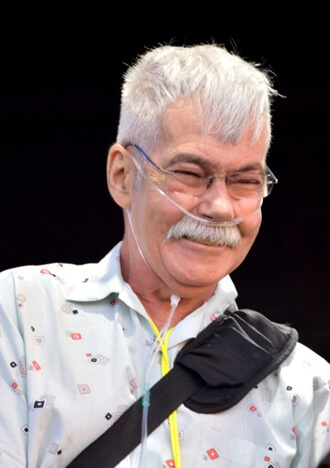

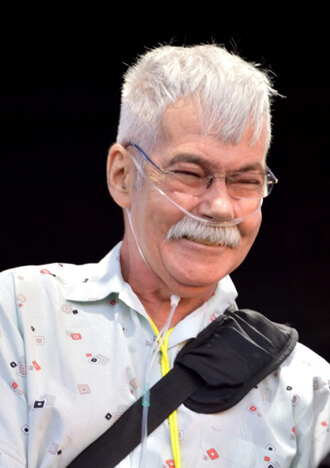

Danny Garvin at last June’s LGBT Pride Rally in Manhattan. | DONNA ACETO

Danny was tireless in sharing his memories of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, particularly those from the Stonewall Inn and the Uprising. Only two individuals have contributed more to documenting the history of that watershed event — Seymour Pine, the deputy inspector who planned and led the raid, and Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt, another Stonewall habitué and a member of the circle of homeless street youth who led the assault on the police on the first night. (Tommy, however, like Danny, did not participate in the violence but joined in the crowd’s resistance to the police attempts to clear the streets.)

Because of Danny’s high value as a Stonewall witness, when the makers of the PBS American Experience film “Stonewall Uprising” asked me whom they should consider as interview subjects for the documentary, Danny was close to the top of the list of names I gave them.

Over my two decades of research and interest in Stonewall, I have seen many frauds step forward and grab the limelight, fooling journalists, documentarians, and historians. Though Danny was always enthusiastic about recalling his experience, he did so selflessly and was never puffed up about his role in anything. And he was certainly the sweetest witness to that historic night I ever came across.

Like many gay men of his generation, Danny — who spent much of his adult life working in hospitals, most recently New York-Presbyterian — contracted hepatitis C, which led to cirrhosis of the liver and then liver cancer. He was also a smoker and suffered from emphysema, so in his final years he was dogged by ill health. Liver cancer and COPD were the causes of his death last month at St. Luke’s Hospital in Manhattan.

Danny Garvin is survived by his sister, Annie Ahearn. His brother, Michael Joseph Garvin, died in 2013.

David Carter is currently writing a biography of movement pioneer Frank Kameny.