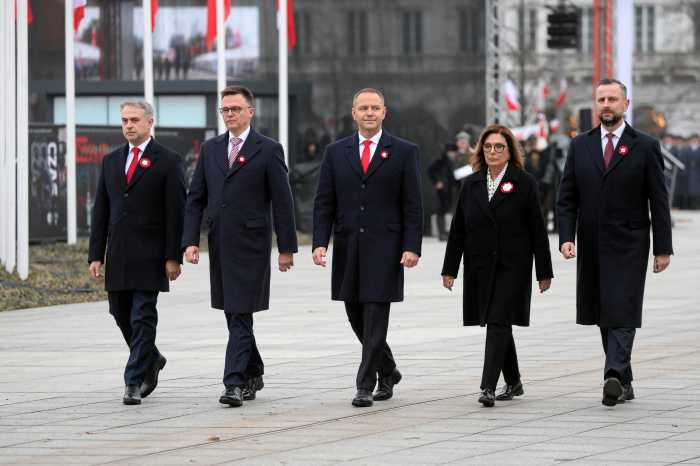

Cuban-born Mabel Cuesta, professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston, at the September 15 public library event. | MICHAEL LUONGO

Nothing about Cuba is without controversy, even how much the country has advanced on LGBT rights. That was clear on September 15, at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center in Harlem, which hosted the panel “LGBT Lives in Contemporary Cuba.”

Featuring Cuban-American and other activists and academics onstage, accompanied by call-ins from two LGBT Cubans based in the island nation, the panel was arranged as a response to a May New York Public Library event featuring Mariela Castro Espín, daughter of Cuban President Raúl Castro and niece to Fidel Castro. She is the head of CENESEX, the Cuban National Center for Sex Education, and she spoke on her work on LGBT issues at the main library on Fifth Avenue at 42nd Street.

Mariela Castro has for a number of years been the public face of Cuba’s LGBT rights movement to the outside world. As the country’s most powerful straight woman, some panelists at the September 15 event argued, she presents a friendly mask that hides inconsistency on the part of the Cuban government and its direct suppression of the nation’s independent LGBT movement.

Cuban-born Mabel Cuesta, professor of Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston, said in spite of queer issues becoming part of Cuba’s official conversation since the 1990s, “nothing truly extraordinary has happened to the LGBT community in terms of rights, the representation of their voices, or governmental power of their presentation.”

The “irony of being visible through a representative of the same heteronormative power that is still trying to give the rights is beyond understanding,” she said, suggesting that if the Castro government wanted to grant equal rights to its LGBT citizens it would have done so already. Mariela Castro’s upbeat words, Cuesta added, are belied “if we take a look at the pictures that show the many police raids that are still occurring in Havana… We need to listen to the voices of the normal leaders, not Mariela Castro’s family.”

Among those voices was Leannes Imbert, who heads the Cuban Observatory on LGBT Rights (OBCUD LGBT) and organized Cuba’s first gay pride march last year. Her phone call from Cuba was broadcast to the audience of about 100 people and translated from Spanish into English by panel moderator Maria C. Werlau, the executive director of the US-based Cuba Archive-Free Society Project. Imbert called herself an “unofficial voice on the LGBT movement in Cuba,” adding, “The situation that the LGBT groups are in in Cuba right now is very difficult. We are being repressed and harassed by the authorities for not really participating through the official channels and in the official version the government wants to convey.”

Imbert gave as an example an exhibit she had been planning on the 1960 UMAPs, an acronym that translates as Military Units to Aid Production, labor camps where gays and other “anti-socials” were placed. Many died in the camps or committed suicide. Imbert said her exhibit was blocked by the government as Mariela Castro and CENESEX were working on their own investigation. Her group’s request for “collaboration,” Imbert said, “has not been accepted, and our voices have been silenced.”

Still, Imbert acknowledged that LGBT rights have “improved around the island, perhaps because of the official version of the events and because of CENESEX.” Under the auspices of the government, provincial LGBT rights groups have begun to proliferate throughout Cuba. Still, she added, for her group, “the doors keep closed” since it is not recognized by the government.

Cuban-American author Achy Obejas was born on the island, but came to the United States as a child. She said, “In 1997, I began to go to Cuba on a very regular basis and stay for months at a time,” visits that gave her a long view on LGBT progress there. Early on, she noticed a cognitive dissonance in friends who remained closeted yet still celebrated the revolution’s ideals.

“I want to talk of how public perception has changed in Cuba,” Obejas said, adding with some trepidation, “I don’t want to toe this message, but Mariela’s work has been, actually, I think been very good in terms of getting non-queers to talk about queers. What she’s done is made the topic more accessible and common in places where this conversation would not be happening unless there was a queer person present.”

Yet as a scientific organization, CENESEX, Obejas said, has “a very specific and particular view of queers, and thus the discussion of homosexuality is more medical and scientific and not so much social, certainly not civil rights, social justice.” That focus, she argued, makes the LGBT awakening in Cuba different from the movements in other countries. There is also now “a bit of a backlash to Mariela’s sort of constantly hammering on queer topics, and a lot of people are over it.”

Others on the panel included Cuban-born writer, poet, and critic Emilio Bejel and Jafari Sinclaire Allen, assistant professor of Anthropology and African-American Studies at Yale University who has studied Cuban LGBT issues. Ignacio Estrada, executive director of the Cuban Alliance Against AIDS, called in from Cuba to participate in the panel. In a phone interview after the panel, moderator Werlau said Estrada became HIV-positive in 2000 and founded his organization in 2003 “after being appalled at the human rights abuses” against Cubans living with the virus. Werlau said foreign journalists writing on Cuban AIDS programs are shown “a Potemkin village tour, but people with AIDS in Cuba are suffering a lot. Cuba presents an image to the world. Cuba sends doctors and medication overseas,” but the island has shortages and improper medical care.

Werlau’s Cuba Archive-Free Society Project works to document human rights abuses in Cuba since the revolution, and it is developing an LGBT archive. Noting she is “the same age as the Revolution,” Werlau said she was eight months old when her family fled the island, and she has been able to return only once, for Pope John Paul II’s 1998 visit. Werlau’s family was at one time close to the Castros — the revolution’s leader was named in honor of her great grandfather, Fidel Pino Santos.

Werlau explained the panel came about after she and others from the dissident community were unable to see Mariela Castro, whom she called “the daughter of Cuba’s dictator,” due to changes the library made regarding access to the May event. Open seating was originally planned, but then the policy was switched to RSVP-only, which she said she learned of too late. “I find that very strange,” Werlau said, adding, “I am not accusing anyone, I am just asking for an investigation.” She and other dissident groups sent a letter to the library and copied it to US government officials.

Jason Baumann, the library’s director of LGBT Collections, worked on both Mariela Castro’s and this event. In an emailed statement, he explained, “Regarding the program with Mariela Castro in May. Initially, this event was posted as first-come, first-served on the Library’s website. However, after news reports announced the arrival of Mariela Castro Espín to the United States and her appearance at the Library, we realized there would be intense interest in this program and decided to create a registration to ensure the event space was safely maintained for event participants and attendees… The registration was solely the Library’s decision and was conducted on a first-come, first-served basis. No one was accepted or excluded from registering for the event for any reason.”

However, due to the confusion over access, Baumann worked on organizing the LGBT dissident panel, asking Werlau to moderate. Werlau said that finding out the panel was on a weekend in Harlem rather than at the New York Public Library’s neoclassical marble headquarters on Fifth Avenue on a weekday — as had been Mariela Castro’s — was “a little disappointing.” She added, “But at least they did it, and I am happy about that.”