Crystal Hudson was cruising along more than a decade into a career in advertising and marketing that included stints at the WNBA, the NBA, and Amtrak.

Then everything changed.

Her mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, which was especially heartbreaking because Hudson is an only child. It forced Hudson to turn into a full-time caregiver, watching her mother struggle to gain access to services and resources and helping her navigate the bureaucracy.

That legwork, Hudson said, “wasn’t particularly easy,” and it made her re-evaluate her own outlook on life.

“At that point in time, I really felt like I wanted to be doing work that just seemed to be more meaningful for me,” Hudson said during an interview with Gay City News.

Former deputy public advocate aims to become first out LGBTQ Black woman elected to City Council

She had worked with the WNBA’s Washington Mystics and the NBA’s Washington Wizards, and then played a leading role in diversifying Amtrak’s national advertising campaigns to include marginalized communities, proving herself as a changemaker early in her career.

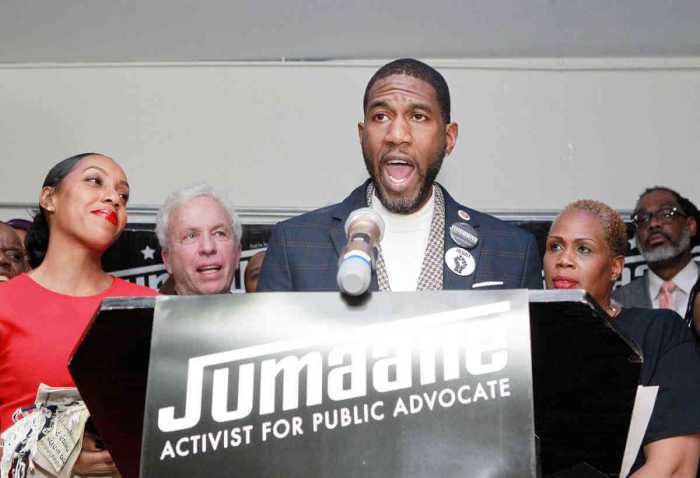

But Hudson wanted to make a different kind of impact — and she followed through, pivoting to a career in public service, where she knew she could make her mark. She worked for City Councilmember Laurie Cumbo and later for Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, serving as deputy public advocate. She now hopes to take her political chops to the next level by mounting a City Council run that would give her a more direct say on how things operate in her district.

Hudson is one of several queer candidates running for city office in a 2021 election cycle during which all five of the Council’s current gay members will be pushed out by term limits. She is mounting an especially historic candidacy, vying to become the first out LGBTQ Black woman elected to city office, as she aims to take over for her term-limited former boss, Cumbo, in the 35th District encompassing Fort Greene, Clinton Hill, Crown Heights, Prospect Heights, and Bedford Stuyvesant.

Hudson is shaping a campaign platform that focuses on championing local issues like bike lane expansions, city rather than state control of the subway system, educational initiatives, additional job opportunities, and more. That approach appears to be a reflection of Hudson’s initial goal when entering the public sector: To be involved on a grassroots level in her own community.

“It was really important for me that I worked for my local elected official,” Hudson said, referring to her role as Cumbo’s chief of operations. “It was there that I learned a lot about the Council — specifically, how decisions are made.”

That work brought Hudson to see issues in a different light — and she started to question whether previous decisions made by local elected officials best served the people of her district.

“One of the things to me, having grown up here, was wondering how a project like Barclays Center had so much community opposition but ended up happening anyway,” Hudson explained. “I think my experience in the Council has given me an inside look into how those decisions are made and also into the really important work of constituent services. I think a lot of times people don’t realize their local councilmember has a direct impact on quality of life issues like potholes, sanitation, and street lights.”

Sometimes, however, a councilmember’s “direct impact” can be too narrowly defined, in Hudson’s view. She envisions a City Council that ditches the tradition of deferring decisions on land use to the local councilmember representing the area where a proposed development takes place. The entire City Council, she believes, should evaluate such decisions carefully, because those choices can have ripple effects extending far beyond a given district.

“I think it’s short-sighted of folks to think that rezoning that’s happening in Inwood or in the Bronx is not going to have a direct impact on those of us who live in Brooklyn or Queens or Staten Island,” she said.

Hudson’s work as deputy public advocate included a focus on issues like environmental justice, health equity, and education, and she especially pointed to the way in which Black girls are pushed out of school by being overdisciplined and overpoliced. In talking about the priority she puts on educational issues, she is careful to include discussion of Black trans girls.

While the City Council has an impact on LGBTQ issues, the most pressing queer political issue at the moment is sitting before the State Legislature, where activists are demanding that lawmakers repeal a loitering law known as a Walking While Trans ban because of the discriminatory way in which cops target trans women of color. Hudson has joined calls to repeal that ban.

She left her job as deputy public advocate just months before the city rose up in a movement that targeted racism and police abuse, putting a big spotlight on the new city budget as advocates called for the City Council and Mayor Bill de Blasio to slash at least $1 billion from the NYPD. Some lawmakers voted against the budget from the left, saying it did not slash enough police funding, and others rejected it from the right. It nonetheless passed, but not without a warning from Hudson’s former boss, Williams, who vowed to use his power to withhold the collection of city property taxes unless more action was taken to hold the NYPD accountable. Hudson’s other former boss, Cumbo, voted in favor of the budget.

When asked how she would have voted if she were a member of the City Council, Hudson initially said only, “It’s a really good question… It’s easy to speculate from the outside.”

She added, however, “Without having every detail available to me, I would say from my vantage point I would have definitely voted against the budget.”

Hudson is calling for a stronger relationship between the mayor and the City Council in order to foster “real conversations and truly productive conversations” around how policing should work in the city.

“I hope to be at the forefront of some of those conversations,” she said. “Personally, I’m a big proponent of communities envisioning and executing plans they think are the best for communities that don’t always involve police, and I think it’s important to hear from communities.”

Hudson’s diverse slate of work experience, she said, has equipped her with a unique perspective that has shaped the way she approaches local issues. Having worked in the private sector, she said she has thought about what it would be like if there were a civil tech innovation hub where government could be a driver of certain technology instead of a follower.

The city, she believes, should begin thinking of the next AirBnb, Uber, or Lyft, rather than having to scramble to “figure out how to deal with something they haven’t thought of.”

Hudson, too, will need plenty of fresh ideas herself as she prepares for a crowded Democratic primary competition next summer, which already features four other candidates — Curtis M. Harris, Michael D. Hollingsworth, Regina Kinsey, and Hector Robertson.

Hudson has kicked her fundraising effort into gear, asking her supporters to chip in when possible, and she’s disavowing donations from developers, police unions, and corporate PACs.

As the campaign heats up, Hudson doesn’t shy away from the historic nature of her candidacy. She has reiterated that point on her website and on social media, where she has also been open about her relationship with her partner, Sasha Neha Ahuja, who is chair of the New York City Equal Employment Practices Commission and a commissioner at the New York City Commission on Gender Equity.

“I think that the fact that my race would be an historic one is just evident that we still have far to go,” Hudson said. “We’ve come a long way, but we have still so much more to do. I think we all live intersectional lives, some of us more so than others, and some of us have more intersecting identities than others.”

That’s why Hudson is underscoring intersectionality in other areas, too, pointing to the need for such an approach to housing, education, homelessness, seniors, and more.

The scope of that lens, she said, should also include the coronavirus crisis, which has disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx communities on multiple fronts ranging from health disparities to the jobs crisis that has emerged. Hudson is calling for a major investment in communities of color in response to the pandemic.

“We’ve seen cuts to Medicaid, cuts to many public hospitals in Central Brooklyn,” she said. “We should be doubling down and investing in public hospitals, social services, job readiness, technology, and small businesses. We need to help small businesses rebound; we don’t need to be looking for new ways to fine them.”

Hudson will spend the next year laying the groundwork for what she hopes is a successful campaign, even if it is going to be in the midst of an unprecedented crisis. Just one election cycle ago, another out LGBTQ candidate — Jabari Brisport — fell short in a bid to unseat Cumbo, but he bounced back this year to win the 25th State Senate District Democratic primary race, putting him on track to become the first out gay Black member of the State Legislature. In 2021, voters in the same Council district will have yet another opportunity to make history.

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.