It was a big deal when the home of the Brooklyn-based Lesbian Herstory Archives officially became a New York City landmark in November.

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on November 22 voted unanimously to designate the Park Slope home of the Lesbian Herstory Archives at 484 14th Street, representing the first LGBTQ city landmark in Brooklyn at the site of a building that has documented so much in the decades since it was officially enshrined in city history.

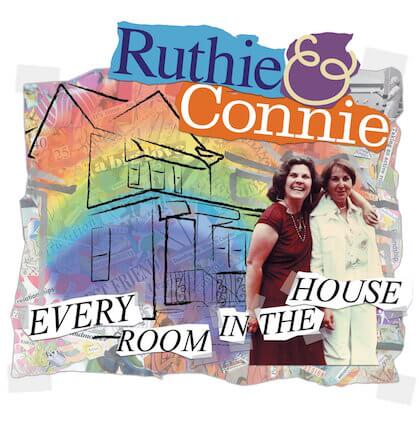

The Lesbian Herstory Archives was founded by lesbian activists Joan Nestle, Deborah Edel, Sahli Cavallaro, and feminist members of the mostly male Gay Academic Union in 1974. From the very beginning, the founders had a long-term vision to “collect and preserve our own voices,” and “a commitment to rediscover our past, control our present, and speak to our future,” according to the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ first newsletter, which was cited in a report by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. The group was also diverse, ensuring a broad representation of experiences.

During its first 16 years, the grassroots volunteer-run Lesbian Herstory Archives grew at Nestle and Edel’s apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The archive outgrew their apartment by 1990 and subsequently moved into the historic building, which was constructed as a two-family dwelling in 1908.

Many preservationists and community members testified about the importance of the building at the commission’s virtual hearing last October.

“Most lesbians don’t inherit queer culture from our parents,” said Colette Denali Montoya-Sloan, the audio archivist at the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ Spoken Word/Audio Project. “The Lesbian Herstory Archives is our birthright and a place where we can go to learn our own history for all, not only lesbians.”

Margaret Herman, deputy director of research at the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission, described the Lesbian Herstory Archives as “the nation’s oldest and largest collection of lesbian-related historical material” during her presentation at the hearing.

A member of the Pueblo of Isleta and a descendant of the Pueblo of San Felipe added that it is “critical” that queer women of color safeguard lesbian history on the land of the Lenape people, who previously lived in the area now known as the New York City.

Amanda Davis, project manager at the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, emphasized the weight of the Lesbian Herstory Archives’ designation and accompanying documentation as a national lesbian resource that could not be ignored in New York City, the United States, or globally.

It signaled “the importance of lesbian history to LGBTQ history, to New York City history, to American history,” she said.

Three of the city’s nine LGBTQ landmarked sites focus more directly on lesbians’ contributions to the movement: The Audre Lorde House on Staten Island, the Women’s Liberation Center in Manhattan, and now the Lesbian Herstory Archives in Brooklyn. Beyond city landmarks, other locations that have recognized their significance to lesbian history include the Alice Austen House Museum on Staten Island, the Henry Street Settlement (founded by Lillian Wald in Manhattan), and the Lorraine Hansberry Residence in Greenwich Village.

The NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation have proposed suggestions to the New York Preservation Landmarks Commission for several years. Davis pointed to hundreds of queer sites — including lesbian sites — that the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission has not recognized, especially those before the 1950s.

Times like now

The New York Preservation Landmarks Commission, city leaders, and LGBTQ and allied historians and preservationists recognized the importance of protecting LGBTQ history, especially voices that have long been invisible.

Sarah Carroll, chair of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, noted the “essential role” the Lesbian Herstory Archives played “in preserving and telling the stories of a mostly unseen community of women, including many who have contributed to America’s cultural, political, and social history.”

Saskia Scheffer, a coordinator at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, expressed in the Landmarks Commission’s report that its mission remained the same almost 50 years after its founding.

“If you don’t collect your own history, you become someone else’s interpretation,” Scheffer, who has volunteered at the Lesbian Herstory Archives since 1989, according to the report.

Davis, an ally, pointed to the significance of landmarking the Lesbian Herstory Archives with the increasing anti-queer climate in the US and around the world.

“It sends a message that we’re still going to keep moving forward to amplify LGBTQ voices and stories,” Davis said.

Councilmember Shahana Hanif, who represents Park Slope in the 39th District, was “thrilled” to see the landmark designation and described it as “an important move to further solidify queer history into the fabric of our city” and ensure “this vital queer space is in our city for decades to come.”

The building

In 1973, the Park Slope Historic District, which included 14th Street, was designated. The house was converted into a three-family residence in 1945. After purchasing the building with community donations in 1991, the Lesbian Herstory Archives converted the triplex into offices, a community space, and one residential apartment for the group’s caretaker on the top floor.

“It was the first building in New York City to be owned by a lesbian organization,” Montoya-Sloan told Gay City News. Davis described the building as “beautiful.”

The Lesbian Herstory Archives temporarily stopped providing tours and hosting live events during the pandemic. It is cautiously reopening to the public.

“Community care is the value of the archive,” Montoya-Sloan said, noting that many of the volunteers are members of communities deeply affected by COVID-19. “We would be remiss if we didn’t acknowledge the healthcare disparities that people experience.”