Over the past several weeks — and this past Friday and Monday, in particular — tragedy unfolded at the Bronx County Hall of Justice on East 161st Street. That tragedy — the trial, closing statements, and conviction of gay teenager Abel Cedeno on the charge of first-degree manslaughter — compounded another tragedy that took place in September 2017, when the long-bullied youth stabbed classmate Matthew McCree to death, because, he has said repeatedly, he feared for his life in a classroom brawl in which the dead boy bounded to the front of the room to attack the defendant.

The terrible loss of life nearly two years ago and the risk that another young life may be wasted in incarceration stem from numerous failures on the part of adults in this city — in both the school system and the criminal justice establishment.

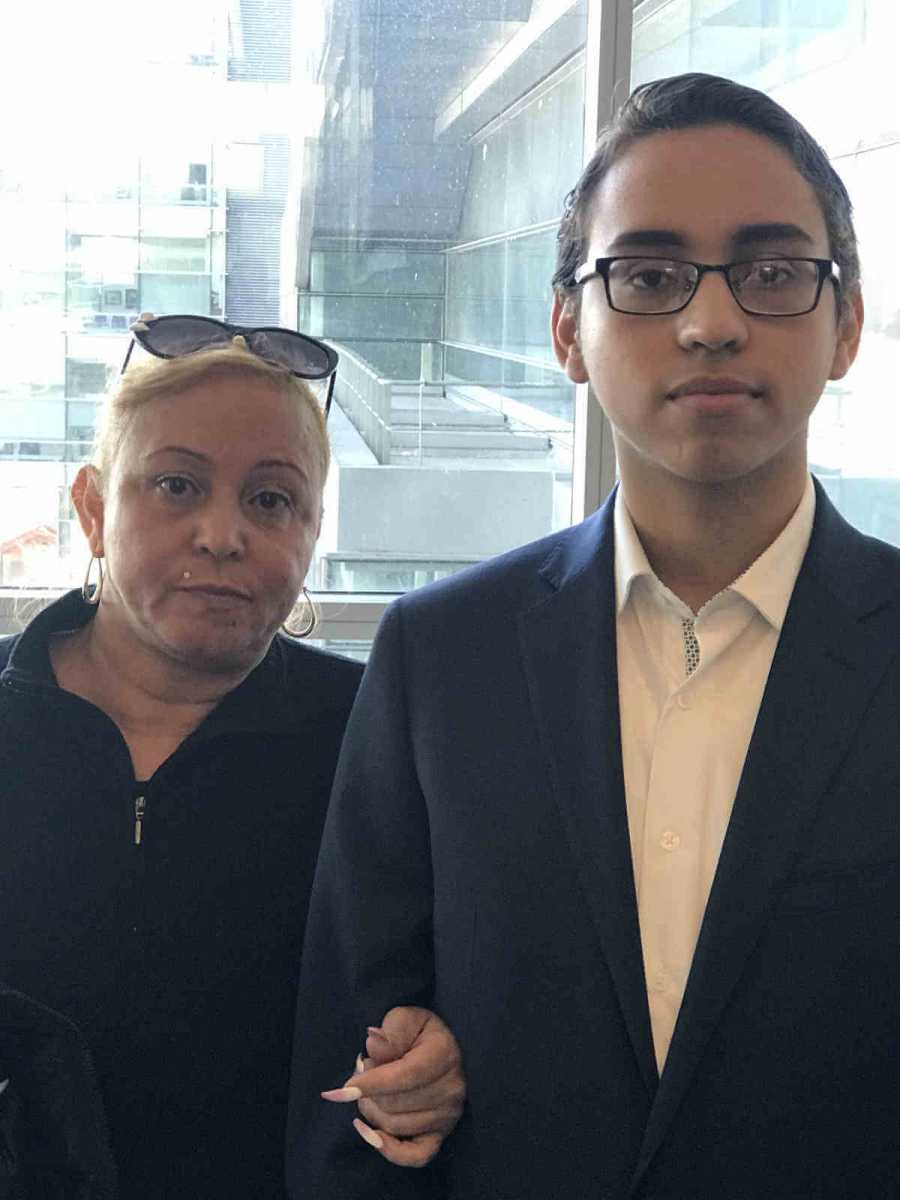

Cedeno, who is 19 now, has been bullied for the greater part of the past decade. He and his mother made multiple requests that he be transferred from the school where he had been made a target — a school so dangerous and chaotic that it was shuttered shortly after the violent events of September 2017 — but those appeals fell on deaf ears. A counselor at the school who testified in Cedeno’s trial, even as she tried to paint the school as having a gay-friendly climate, acknowledged that she had heard from him on numerous occasions about his bullying, but never made a report to the Department of Education. The responsibility for that, she said she assumed, was the dean’s.

Prior to the 2017 stabbing incident, Cedeno had never been bothered by McCree, but he has said he was aware of the youth’s reputation. A friend of Cedeno had suffered a beating at McCree’s hands, the defendant said. The defense developed evidence that McCree and his friend, who was injured in the 2017 brawl, were gang members, but Judge Michael A. Gross did not allow any evidence of the two youths’ prior bad acts to be introduced.

Several factors in the public record, however, lend credence to the defense claims about the two young men who were stabbed.

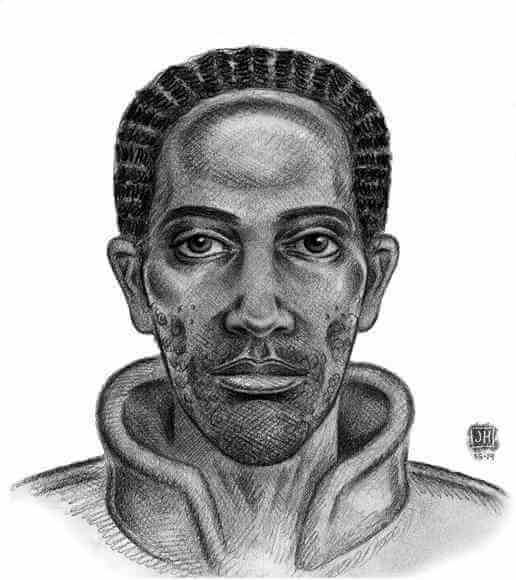

Several months after the incident, McCree’s brother, Kevon Dennis, was arrested on felony charges of using a knife just hours after McCree’s death to rob student witnesses of evidence, including cell phones that might have included footage of the deadly encounter. Those charges were later dropped by the office of Bronx District Attorney Darcel Clark, who was simultaneously pursuing murder charges against Cedeno — which the grand jury later reduced to manslaughter. Defense efforts to have a special prosecutor step in to avoid the obvious conflict of interest faced by the Bronx prosecutor were denied by the court. Dennis, meanwhile, on another occasion attempted to jump Cedeno outside the Bronx court.

A student witness presented by the prosecutor last week was forced under defense questioning to admit that when she learned in late 2017 that Cedeno was free on bail, she posted to Facebook an alert that she had spied him on East 182nd Street and that “theres no way” he “is walkin that comfortable nd not gettin touched.” She added that McCree’s friends “needa step up they game up 100” percent.

Which students were called to testify was, in and of itself, a troubling aspect of the trial. Defense attorneys have said that the Department of Education at every turn frustrated their efforts to contact the students who were in the room when McCree died. The prosecutors, however, produced a blizzard of witnesses of their choosing, notifying the defense of their identities just one day in advance of their testimony. A new state law passed this year, thankfully, will require district attorneys in the future to turn over material to be used at trial in a far more timely and equitable way. As it was, Cedeno was only able to let his attorneys know that the young woman who had threatened him on Facebook was selected by the district attorney’s office to offer testimony against him as he watched her on the witness stand.

Perhaps the clearest sign that the criminal justice system has no understanding of what Abel Cedeno had faced in his career in the city’s public schools came when Assistant District Attorney Nancy Borko delivered her closing statement last week and ludicrously charged that Cedeno had arrived at school the day of the fatal encounter “bent on creating an opportunity to use” the knife he had purchased on Amazon to protect himself to “prove that he’s not a pussy… to prove that he’s tough.” To be fair, in using the word “pussy,” Borko was quoting a slur that Cedeno himself threw out at the students who were pelting him with pens and wads of paper that day.

What this veteran prosecutor seemed to have no appreciation for, however, is that he chose that word precisely because that was the term that over and over again had been used against him. On one of the occasions that his mother, Luz Hernandez, joined him in meeting with school officials to discuss his bullying, Cedeno testified that he would not say he was gay in front of her.

“I thought it was something to be ashamed of,” he testified. “The bullies said I was gay and ‘you shouldn’t be gay.’ They were bullying me for something I have no control over.”

Now, a young gay man who suffered continual bullying in a school system that never gave a damn enough to listen to his pleas for relief faces the threat of further victimization in a lengthy prison sentence. Should Judge Gross, in determining sentencing on September 10, grant Cedeno youthful offender status, the young man could avoid the most severe penalty and also be eligible for rehabilitation diversion to better ensure that he is ready to reenter society on his release.

If Abel Cedeno is not given that consideration, may God have mercy on him. And on Judge Gross, ADA Borko, District Attorney Clark, and all the adults who failed Cedeno and the dead and the injured students from his school.