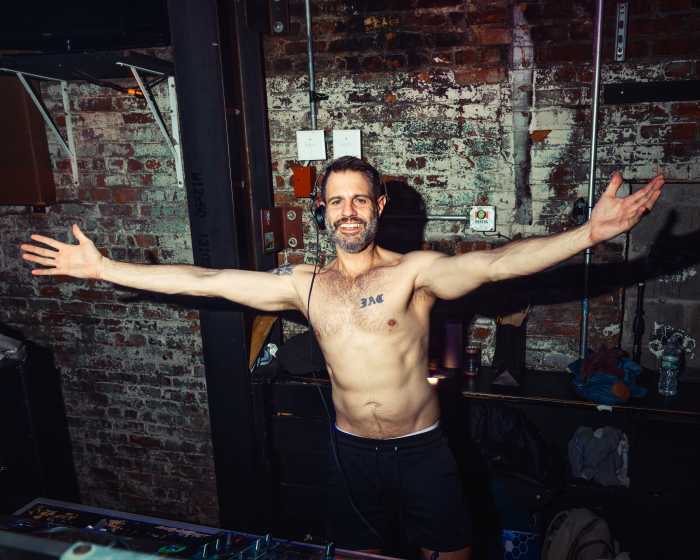

Josh Walden and Dwayne Croft in a lively moment in the Glimmerglass Festival's production of Meredith Willson’s “The Music Man.” | KARLI CADEL/ THE GLIMMERGLASS FESTIVAL

Since taking over the Glimmerglass Festival last year, Francesca Zambello has scheduled a classic Broadway musical each season with opera stars performing the ori ginal score unamplified. This summer, she chose Meredith Willson’s “The Music Man” (1957), starring Cooperstown native Dwayne Croft as the fast-talking confidence man Harold Hill and opera’s eternal ingénue Elizabeth Futral as Marian the Librarian. Both displayed a natural flair for the genre despite being rather mature for their roles and vocally overqualified. Director and choreographer Marcia Milgrom Dodge shifted the time setting from 1912 to 1946. This made nonsense of period-specific references to “traps,” “the Wells Fargo wagon,” and “ladies corset covers,” but small-town mores remained unchanged over the three decades and eventually you forgot the anachronisms.

Croft’s relaxed, vulpine stage presence and unaffected diction reminded me that one of his best operatic roles is another quick-thinking schemer with a line in fast patter –– Rossini’s Figaro. Futral’s Marian was initially a plain Jane in a snood and horn-rimmed cat glasses –– a dead-ringer for Lily Tomlin’s telephone operator Ernestine. By the second act, Futral’s Marian had transformed into her usual winsome charming self. Futral’s delivery of the dialogue was worthy of a Broadway veteran, but a few sung lyrics got lost in her upper register.

Jake Gardner’s Mayor Shinn was all befuddled bluster, while Cindy Gold as Mrs. Paroo was delightfully meddling and warm-hearted. Ernestine Jackson missed many comedic opportunities as Eulalie Mackecknie Shinn (no one can match Hermione Gingold’s delivery of the word “Balzac!” in the movie). Josh Walden was an old-school vaudevillian scene-stealer as Marcellus Washburn –– his high-stepping “Shipoopi” number was a highlight.

James Noone’s set design utilized a blown-up reproduction of Grant Wood’s 1930 landscape painting “Stone City, Iowa” as a fixed backdrop fronted by mobile set pieces and flying scenery that kept the show moving seamlessly. Dodge’s direction had no other innovations outside of switching eras, but her spirited choreography flowed easily in and out of the action. John DeMain’s fast tempos stressed the brassy march elements of Willson’s score.

Glimmerglass alternated this family-friendly standard with Kurt Weill’s seldom performed Broadway folk opera “Lost in the Stars” (1949), an ambitious, high-minded failure. Weill’s last completed work is modeled on “Porgy and Bess,” with a preachy social message. Maxwell Anderson’s poetic libretto reduces the characters of Alan Paton’s novel “Cry the Beloved Country” to flat, simplistic symbols rather than fully-rounded complex human beings. The story is set in South Africa where black priest Reverend Stephen Kumalo searches for his wayward son Absalom in the poverty-stricken slums of Johannesburg. Kumalo eventually finds Absalom in prison after he was arrested for the shooting murder of an unarmed white man during a botched robbery attempt. Absalom is condemned to death, while his shattered father struggles with his faith. Weill and Anderson are using the apartheid setting to comment on the racial oppression that drove Weill out of Nazi Germany in the 1930s as well as on the burgeoning US civil rights movement of the ‘40s.

The title song, “Lost in the Stars,” which is the only standard from the show, comes at the end of Act I when Kumalo has learned that his son is a murderer. Its theme of how we are all lost in the universe and ignorant of God’s plan rings emotionally false in the dramatic context. The philosophical and reflective tone seems removed from the shock and anger Kumalo is feeling at that moment.

The other pieces are genre numbers for secondary characters, flat choral sections, and torch songs for Absalom’s pregnant fiancée Irina. Absalom and the white characters don’t sing at all. Act II deals with Absalom’s trial and execution, and here the music should reach operatic heights, but the score thins out. On the day of his son’s execution, when Kumalo vows to leave his ministry he is only given a brief reprise of the title song’s introduction.

The final scene is a tearjerker. James Jarvis, the stiffly bigoted father of the murder victim, enters Kumalo’s church with a changed heart, tells the grief-stricken Kumalo they have both lost sons, and offers his friendship. In just the previous scene, however, this character advised his grandson not to speak to black children. Where this wildly unmotivated 11th hour conversion comes from is left to the audience’s imagination. At this point, the white and black congregations come together in song. The authors’ liberal ideals sweep aside social history and the realities of apartheid.

It is a credit to the performers and the director Tazewell Thompson that during this final reconciliation of races, all around me I heard audience members sobbing. Eric Owens’ Kumalo was totally crushed by devastation and loss, while Wynn Harmon as the elder Jarvis had a quiet restraint that held bathos at bay. Owens, Glimmerglass artist-in-residence for the 2012 season, sang with a deeply burnished voice like a church organ and acted with simple truth that made this modest man seem like a giant. He seemed to be performing in a different, greater musical work.

This was a co-production with Cape Town Opera Company, and many South African singers took supporting roles. Conductor John DeMain made the best case he could for Weill’s patchy score. Thompson’s production was stark and placed the emphasis on the performers –– the sets were earth-toned corrugated metal walls suggesting the desperate poverty and harsh landscapes that shape the characters’ fates. All this production needed was music that fleshed these characters out and a book that gave them reality, depth, and grit.