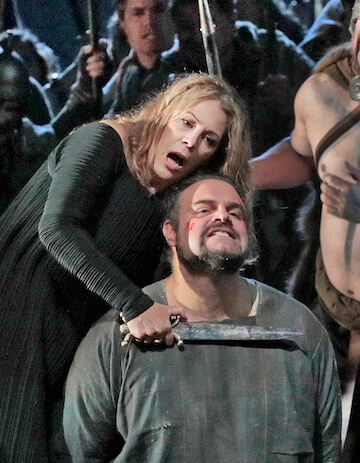

Anthony Roth Costanzo in the title role of Handel’s “Giulio Cesare” at Houston Grand Opera. | LYNN LANE

Lincoln Center’s annual White Light Festival kicked off with a pleasing program November 1 at the Rose Theater, focused on a reprise of the Pergolesi “Stabat Mater,” some of the most inspiriting — and certainly influential — music of the 18th century, directed and choreographed by Jessica Lang.

First seen at Glimmerglass four years ago, Lang’s staging deploys nine outstanding dancers, who often double as the Marian and Christ figures otherwise embodied by (or described by) the two vocal soloists. Speranza Scappucci led a fine group of musicians with alacrity; a bit more rehearsal might have yielded even tighter string coordination, but the instrumental solos all emerged well. Bradon McDonald’s subtly shifting costuming (earth tones yielding to blue) and the transfixing set of two movable trees, reconfiguring in crossed patterns, yielded memorable imagery. So did Lang’s choreography when not too literally executing the hymn’s text.

It’s remarkable how gracefully both Andriana Chuchman and Anthony Roth Costanzo fit into the piece’s danced portions, even while singing very beautifully indeed. Occasionally, the soprano’s upper middle notes sounded a touch too “operatic” in scale, and the countertenor, whose trills and sculpted phrases proved fantastic, at times sounded slightly occluded at range ends. Still, a lovely experience.

Anthony Roth Costanzo stars at Lincoln Center and as Giulio Cesare in Texas

One understood Costanzo’s work ethic (and slight exhaustion) when — after repeating the Pergolesi the following day ——he returned two nights later to his first-ever series of “Giulio Cesare” title role performances for Houston Grand Opera. Since Hurricane Harvey, the valiant company has been performing in an improvised space in a huge, impersonal convention center. It was better than nothing, and the shows are going on, but both sightlines and acoustics proved problematic, causing a sense of audience remove in terms of the response.

Some years back, and in more accommodating venues, James Robinson’s “filming a silent movie” concept must have been charming, but this gambit has staled, and — apart from the spiffy costumes (James Schuette) and Marcus Doshi’s fine lighting — everything fell quite flat. Orchestral sound registered mushily. Even singers gifted at comedy like Heidi Stober (Cleopatra) and Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen (Nireno) were pushed into shtick, though Cohen sounded terrific in his sole aria. The direction countenanced and encouraged whooping and cackling over the music. For future note, Handel is not “Hellzapoppin’” even when amusing, and proves less amusing when mirth is forced. Almost no one laughed at anything.

The boyish Costanzo — surrounded by extremely tall colleagues — mustered sufficient military bearing to be a credible Casere (He also tap danced gracefully.) The part is a huge sing but he encompassed its testing portions well thanks to keen phrasing and technical savvy. His precision made the ecstatic “Se in fiorito” and elegiac “Aure, deh, per pietà” particularly memorable. This part should serve him well, as was the case with two distinguished Handelians onstage, Stephanie Blythe (Cornelia) and David Daniels (Tolomeo). Both now work within some limitations — the mezzo of breath, the countertenor of range — but as soon as they open their mouths, both produce their characteristic, instantly recognizable timbres, and plenty of it.

That sense of instant connection with the music and audience went lacking in Stober’s highly accomplished but rather anonymous singing. She and her voice — when not at full tilt, when it takes on a soubrette edge — are lithe and pretty, but the takeaway is visual. Very young, Megan Mikailovna Samarin (Sesto) had the same anonymity and needed a far more stylish Handel conductor than Patrick Summers to imbue her work with the requisite vocabulary. I’m still shocked that Summers cut “Cara speme” — Sesto’s greatest aria — down to its first A section, especially as that was Samarin’s best moment. Bass Federico De Michelis (Achilla) showed real promise but must learn how to land ascending intervals.

On November 2 the Met revived the beautiful Anthony Minghella staging of “Madama Butterfly” — still, after 11 years, the best production Peter Gelb has imported. Some of the stage magic seemed slightly dimmed with time (and mid-season revival rehearsal time limits) but it still makes a moving evening, not only diverting but thought-provoking. Debuting conductor Jader Bignamini presided with appropriate stylistic panache and due urgency while allowing for the score’s quieter moments to work their charms; definitely a positive acquisition.

Hui He returned to the title role with pleasing though not historic results. Unlike many who tackle the part, the Chinese soprano commands a genuine spinto-weight voice that never sounds overtaxed by Puccini’s varied demands. Moreover, it boasts uncommonly handsome timbre and is used with some variety of dynamics and thoughtful shading. She’s not a riveting interpreter but handled herself with seriousness and dignity and made the necessary points: certainly well worth hearing in the part.

Roberto Aronica (Pinkerton) has commendably made himself a more plausible stage figure but his tenor remains blaring and undistinguished. David Bizic, on the other hand, wields a far finer, fresher baritone than many Sharplesses command and gave a fully worked-through characterization. Maria Zifchak’s Suzuki — with this show from the beginning — remains a moving presence and audience favorite but on this occasion sounded edgy on top. No one among the small roles registered much quality except lush-voiced Juilliard grad Avery Amereau as Kate Pinkerton.

On October 27, the Boston Symphony played Berlioz’s “Damnation de Faust” under veteran maestro Charles Dutoit. Both orchestra and conductor have specialized in the composer’s music and the familiarity with his uniquely orchestrated idiom told, even though the afternoon’s performance proved estimable rather than duly exciting.

The three leading soloists — Paul Groves, Susan Graham, and John Relyea — have been singing Faust, Marguerite, and Mephistopheles for many years, and it showed in ways both salutary and poignant. None of their instruments remains in immaculate form, but all sounded quite good and at times the tenor and especially the mezzo made very lovely sounds indeed. Relyea’s voice is a bit grayed but he seems to have recovered some of his younger form.

All three use the French language with skill and understand Berlioz’s style. So — especially in the wondrous fourth part — the singing proved quite satisfying. Dutoit acknowledged the horn underpinning Graham’s glowing “D’amour l’ardente flamme” and the fine work of both choruses.

David Shengold (shengold@yahoo.com) writes about opera for many venues.