Off Broadway show about Freddie Mercury not yet worthy of adulation

Labels. We love to hate them, but without labels we’d be lost.

Whether describing race, occupation, socio-economic status, sexuality, or underwear, labels offer us guidance and help set expectations. But when labels mislead, disappointment is sure to set in.

Such was the case for me on opening night of the latest incarnation of “Mercury: The Afterlife and Times of a Rock God,” Charles Messina’s inspired one-man drama where Freddie Mercury, on Judgment Day, confronts God, his life choices, and his inner child. The press materials crowed that the “highly acclaimed” one-man show was moving out of the fringes to “Off Broadway.”

Off Broadway. This label evokes visions of other recent one-person Off Broadway sensations, such as “I Am My Own Wife” (a high benchmark to be sure, since its transfer to Broadway) starring Jefferson Mays or other Off Broadway rock tributes, such as “Love, Janis” with its dead-on Janis Joplin impersonators and pounding live rock band. I assumed that since its original production in 1997 “Mercury” had been strengthened and polished along the way and was now ready to shine.

Imagine my surprise when the Off Broadway theater turns out to be The Triad on West 72nd Street, little more than a tiny, chair-choked cabaret lounge above a Japanese restaurant.

The set, for which no one takes credit in the program, is a sad, slapdash jumble. The music, all pre-recorded, is a let down. The obscure introductory song, as we sit in literal and figurative darkness puzzling over its connection to the show, plays on far too long.

We never hear actual Queen music, save for the stomp-stomp-clap snippets of “We Will Rock You” that make a promise it can never deliver. And when Mercury finally picks up the acoustic guitar, on view for the entire performance, it turns out to be broken. He never strums or sings a note.

Freddie Mercury had trouble with labels. He spent his entire musical career fronting the popular British band Queen in the 1970s and early 80s and avoiding the label “queer.” Living under his new name (he was born Farookh Bulsara), he also avoided the label “Persian,” happy to deny his heritage. He spent the last years of his life, much to the ire of ACT UP and similar groups, dodging the label of “AIDS victim.”

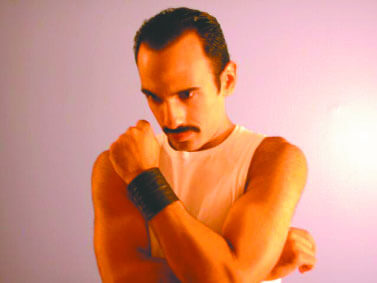

The label Mercury most aspired to was “Rock God”—he even sports a large Superman logo on his white ribbed tank top—but, as the play makes clear, he wasn’t entirely comfortable with that label, either.

The moderately provocative show is framed, not so originally, but effectively enough, with the oddly merry Mercury loitering outside the Pearly Gates, pleading to God to let him in. The date is November 24, 1991, and Mercury has just succumbed to AIDS. While suspended in purgatory, bits of his life flash before our eyes—at his childhood home in Zanzibar, at boarding school in India, at art school in England. God, evidently no rock fan, is in no rush to pass judgment.

Of course, there’s no dramatic tension surrounding whether the errant rocker will be admitted to heaven. Mercury’s shameless look-at-me lifestyle, with its silver trays piled high with cocaine and sexcapades with loads of blokes, not to mention living a lie––he even hid his sexuality and illness from his family––would seem to guarantee an express pass to hell.

Is Amir Darvish, who plays Mercury and a handful of other characters, a terrific talent? Certainly. He prances and preens with an amazingly crazed exuberance, holding our attention for an intermission-less 80 minutes. And with dark complexion, hairy chest, lithe body, and thick moustache, he looks enough like the swarthy Mercury––minus the overbite.

Though Darvish has the poses down pat, when it counts most his moves simply don’t command the authority of a rock star. Despite his energy, transitions from one persona to the next can be clunky; it’s not always immediately clear who’s speaking. Writer/director Messina should have seen to that.

Yes, there are moments of genuine emotion. Mercury’s clashes with Bulsara, his former self, once you figure out whom he’s shouting at, are chillingly powerful. His “fuck you” refusal to apologize for not being the out-and-proud role model the gay community wished him to be, both as rock hero and AIDS activist, draws unexpected empathy.

And who knew Mercury was such a wit? The Oscar Wilde of glam rock and roll, Mercury lobs one aphorism after another, like “Shyness is the enemy of fame” and “Guilt is the enemy of pleasure.” In coming to terms with his life, and death, he quips, “Old flamers like me, we aren’t extinguished. We burn ourselves out.”

Despite these intermittent flashes of brilliance, this small, promising one-man show should remain in theatrical purgatory until the production is re-tooled further. It does not yet deserve a home labeled “Off Broadway.”