Chuck Knipp returns to New York to perform Shirley Q. Liquor at the Slide

The character is described as a single mother of 19 children born out of wedlock and on welfare. When in character as Shirley Q. Liquor, Knipp, a resident of Long Beach, Mississippi, speaks in an exaggerated black Southern accent and mispronounces words. His act consists of poking fun at African American female names, holidays such as Kwanzaa, Ebonics, African American women in jail, and a host of other topics related to blacks.

“Our goal tonight is to educate patrons, to give them some different analysis about what they are going to see,” said protest organizer Colin Robinson, director of the New York State Black Gay Network.

The group of 15 to 20 protestors, from the Network and Brooklyn’s Audre Lorde Project (ALP) which serves queer people of color, lined the entrance to the nightclub, handing out leaflets. Printed on one side of the leaflet was a photocopied picture of the Shirley Q. Liquor character’s face with the statement, “Shirley Q. Liquor is not a cabaret act. It is a Racist, Sexist, Misogynist Attack.” On the reverse was “an open letter to lgbtst communities” outlining extensively the demonstrators’ position and call for action. The statement was excerpted from a longer letter disseminated in September, 2002, in the wake of Knipp’s last appearance in New York City, at the View bar in Chelsea. At that time, a non-violent demonstration by protesters led police to shut down the club.

The demonstrators said that the character’s portrayal of working class, African American women is not only offensive, it fuels hatred and animosity among whites towards people of color.

“The images and language that [Knipp] uses remind us of the images and language that have led to violence against people of color, particularly African American women,” said organizer Trishala Deb, ALP’s program coordinator. “These are not benign performances, but part of a history of racism and they are not acceptable.”

“I love black people, always have,” Chuck Knipp said in his dressing room after his performance. Traces of the coal black makeup he applies to his face were still under his fingernails. “In my youth, black women nurtured me.”

Knipp, a registered nurse and Quaker minister, said he was inspired to go to nursing school because of the character of Julia, played by actress Diahann Carroll, on the 1960s television show of the same name.

“She handled racism with so much elegance,” Knipp said. “I think there is a huge reservoir of affection between Southern black women and white gay men. I hear that all the time from fans. Gay men have always had a symbiotic relationship with black women. It is one of the most understated but ubiquitous things.”

Knipp said he was taught to speak the black, female dialect he uses in his act by his best friend in college, a black gay man named Tony Steele.

“Tony taught me to talk black,” said Knipp, who first performed the Shirley Q. Liquor character on the radio.

“I’m familiar with racism, I think it’s stupid,” he said. “Now, do black people and white people and Cajuns and people from Maine talk differently? Yes they do.”

When it came to doing the character on stage, Knipp said he saw no other way than to do it in blackface.

“I’ve read a lot about minstrels,” he said. “I know it touches a nerve. I want to get people worried about it.”

Organizers said they were concerned that, despite the outcry from groups of color over the last incident involving Shirley Q. Liquor, an entertainment promoter would bring Knipp back to New York.

“It’s not just about the performer, it’s about the promoters,” said Robinson.

Daniel Nardicio, the event’s promoter, acknowledged that the character plays on stereotypes.

“If Shirley is misogynist, then every drag queen is,” he said. “This is modern parody. And race is also up for grabs. Everyone is a little bit racist and misogynist, but Shirley distills all that, so that the [racist] image becomes less painful.”

Nardicio added that “I never want anyone to feel disturbed [by any event I promote].”

Gay City News was unable to reach the owner of the Slide/Marquee for comment.

Many patrons defended Knipp’s right to perform the character on the grounds that it was no more offensive than African American comics’ parodies of gay men.

“I watch BET [Black Entertainment Television] every night and they prance around and talk about gay people and everyone thinks that’s funny,” said audience member David Gosbin. “Shirley Q. is just observing a portion of society.”

“I think that she’s just one character and to relate that to an entire group of people shows racism on [the demonstrators’] part,” said attendee Jason, who declined to give his last name.

The ALP’s Deb said her organization tried to open dialogue with Knipp via e-mail, but they never received a response.

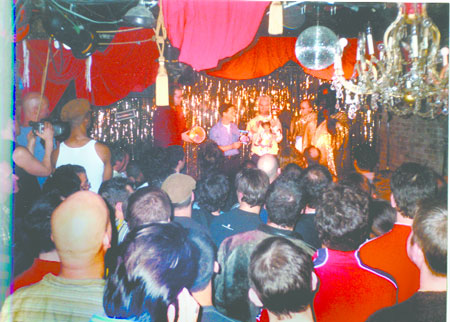

The crowd inside the Marquee, the ground-level cabaret club attached to the Slide where Knipp performed, was filled with an estimated 150 patrons, predominantly white gay men. A couple of die-hard fans wore t-shirts plastered with a black face and the quote “How You ‘Durrin’,” one of Shirley Q. Liquor’s signature phrases.

Less than ten people among those attending were people of color. The woman serving at the bar, and both go-go dancers, a man and a woman, were African American. When asked whether black women typically were go-go dancers at the gay male club, a Slide/Marquee employee replied, “No. It’s to show that we’re not racist.”

No African American audience member would comment, except for a young gay man named Xavier, who withheld his last name.

“It’s not safe comedy, that’s for sure,” he said. “The way it’s presented, it’s just absurd in the vein of comedy. Shirley Q. makes fun of everybody. Why would that be a charged political statement? It pisses me off. I feel that we can get to a point where we can make fun of each other, hence ‘South Park,’ the ‘Dave Chappelle Show,’ ‘The Simpsons.’ To equate Shirley Q. with Al Jolson [the minstrel] and performers from days gone by I just don’t think is valid. It’s more than just race. It’s religion, class, sexuality. Who is to say that any of these topics are off-limits?”

“The power of drag performance is always drawn directly from abjection, from those who are abject in the society: black women, drunk women, abandoned women, ugly women,” said Michael Warner, author of “The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics and the Ethics of Queer Life,” who was in attendance at the event.

Knipp took the stage amid rapturous applause. When the clapping died down, the chanting of the protesters outside could be heard. “It’s a racist, classist, misogynist attack. Shirley Q. Liquor’s not a cabaret act,” they yelled.

“There may be people more racist, misogynist, classist than me,” said Liquor, theatrically mispronouncing the word “misogynist” to the audience’s approval. “But I’m certainly the most ‘ignunt’”––the performer’s well-known way of saying ignorant.

During a one-hour comedy routine, Knipps’ Liquor talked about flying aboard “Ebonics Airways,” about going to the doctor to get a “pop quiz” instead of a “pap smear,” and about Chivonne, a black woman in prison, amidst a good deal of racially charged comments.

“Look at all the white people,” Liquor said. “I never seen so many white people not smoking since Mississippi tried to execute me.”

“I know that the first day of Kwanzaa is for the first black people in space,” the character explained. “The rest is a bunch o’ bullshit.”

“Y’all need to be ashamed, white people,” she told the crowd. “You ain’t right.”

Among many songs Knipp performed, one was called “Who is my baby daddy?” during which Liquor held a white baby doll, telling the audience, “I wish I could get some child support for her.”

When the set was over, the crowd dispersed to the music of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the black South African choral group.

“I take [the performance] as being a white person commenting on other white people,” said audience member Kevin Gonzalez, who is Latino. “In the context of a drag performance, I don’t think that’s offensive.”

“I found it disturbing,” said Terry Liu, who is Asian. “First of all, most of the crowd was white. I don’t really know the precise history of the entire blackface aspect, but I don’t think I need to. I just felt very, very disturbed.”

We also publish: