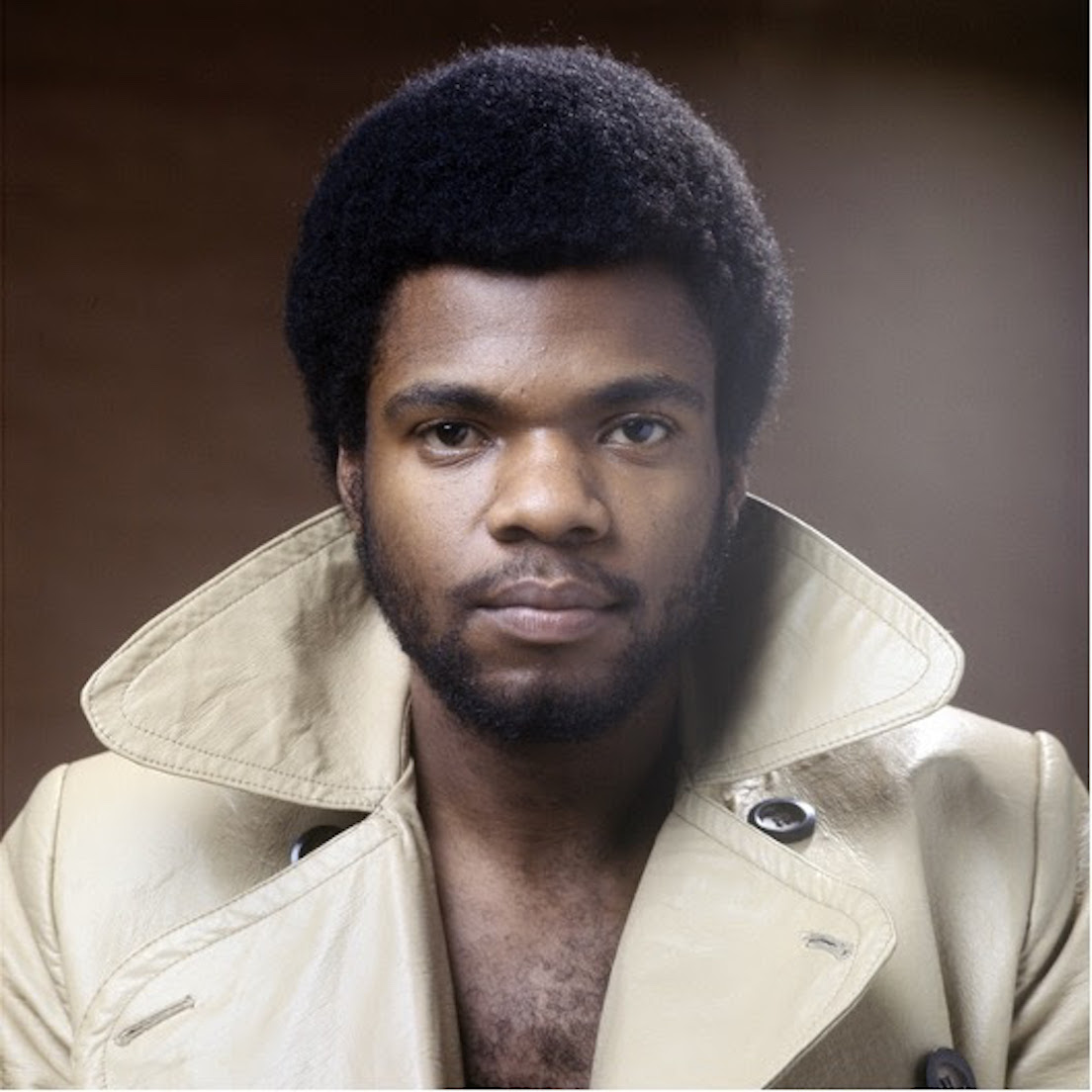

A gap exists at the heart of gay director Paris Barclay’s documentary “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It.” It’s Preston himself. A singer and keyboardist who started performing gospel music when he was 3, he racked up an enviable number of gigs as a sideman. Eric Clapton recalls watching his 1957 performance on “The Nat King Cole Show.” Touring with Little Richard as a teenager, he met the Beatles before they became stars. Teaming up with the band again, he played keyboards on their albums “Abbey Road” and “Let It Be,” as well as their final live performance in 1969. (“Get Back” is credited to “the Beatles with Billy Preston.”) In the ‘70s, he achieved fame as a solo artist. This all came crashing down. When his success began to falter, he became addicted to crack and alcohol, developed serious financial problems, and was arrested repeatedly.

Despite Preston’s musical accomplishments, the film circles around a man who remains enigmatic long after death. Much, although not all, of this mystery stems from Preston’s secrecy about his gayness. He was shaped by a church full of closeted gay men singing gospel, such as Rev. James Cleveland, alongside homophobic preachers.

Since Preston never spoke frankly in public regarding his sexuality, “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It” relies on the words of musicians who knew him. Author David Ritz likens the Hammond B-3 organ, with its two keyboards and set of petals, to the multi-faceted nature of Preston’s personality. Full of footage of his performances, the film shows that he spoke through his music, rather than interviews, “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It” can only speculate about Preston’s own thoughts.

Preston had a hand in several genres and cultures. Beginning in gospel, he worked with Black musicians sharing such roots. Ray Charles’ “I’ve Got A Woman,” which secularized gospel into an R&B love song, was a revelation for him. But he was equally enthusiastic about the Beatles. In the documentary’s exhilarating opening scene, he’s onstage with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and Ravi Shankar at the 1971 benefit concert for Kampuchea. Tellingly, the focus is on him for once, performing “That’s The Way God Planned It.” He gets up from his organ during the instrumental break to dance joyfully. None of the interview subjects address how he felt about working with white musicians, especially as a sideman or opening act, but they opine that he felt humiliated by having to visit Black radio stations in the late ‘70s and attempt to cross over back to his own community.

No one in “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It” reports knowing about his sexuality until the ‘70s. One subject recounts seeing his “cousins” accompany him on tour. There was a secret “don’t ask, don’t tell” bargain regarding his sexuality, as most of the people around him could guess the details. In 1979, he embarked on a fake romance with his duet partner Syreeta Wright. He seems to have been extremely lonely: “You Are So Beautiful” was written for his mother, not a lover. Several people speculate that he would’ve been happier if he’d settled down in a long-term relationship.

Up to a point, “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It” fits into a standard formula of documentaries about musicians. Assembled from talking heads interviews and music clips, the film compresses Preston’s life into a rise-to-fall-to-partial rise storyline. While it’s not a hagiography, it brushes past the fact that Preston sexually assaulted a 16-year-old boy. (A judge opines that this would never have taken place without Preston’s addictions.) Of course, many musicians have committed the same crimes and even sung about them without facing legal consequences. His problems with drugs also helped tank his career: hired to play piano on a TV talk show, he sold its equipment for money to buy crack.

The ways in which Preston’s life evades that “Behind The Music” narrative are the most interesting aspects of “Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It.” In all respects, Preston was reticent about his emotions. When his brother perished in a gas explosion, he didn’t speak about his grief. The documentary connects his problems with the fact that he was molested as a child performer. But one comes away feeling even more curious about the man.

“Billy Preston: That’s The Way God Planned It” | Directed by Paris Barclay | Abramorama | Opens Feb. 20th at Film Forum