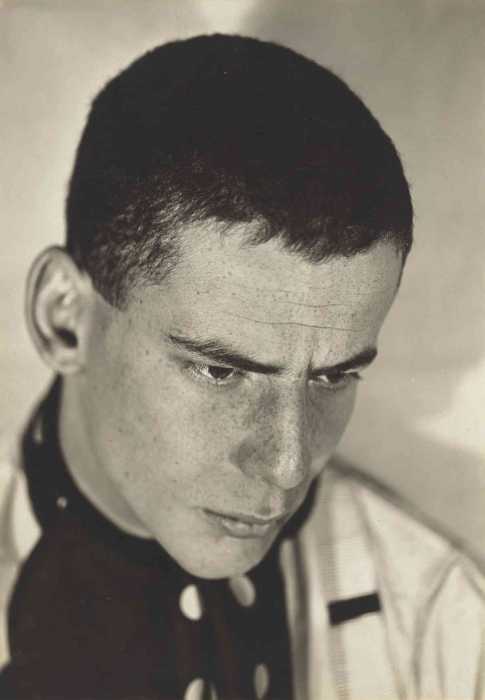

In his lifetime (which began exactly 100 years ago this August 25), Leonard Bernstein was a polarizing figure. To some he was an angel of musical talent: a virtuoso pianist, an expert proselytizer for all forms of music in the mass media, and a genius composer and conductor of classical music, jazz,and Broadway.

But the classical music critical establishment demonized his showmanship, ego, eclectic tastes, and self-promotion, deploring what they perceived as vulgarity and a breaking down of established divisions and standards. A true polymath, Bernstein was trying to be too many things at once to succeed at one, many said.

The 2018 Mostly Mozart Festival programmed a staging of Bernstein’s 1971 “Mass” in celebration of the centenary of his birth. The contradictions of the man and his music resonate through this controversial work, which addresses Vietnam-era political, social, and spiritual conflicts that are more relevant than ever in our newly polarized America. Commissioned by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, this two hour “theater piece for singers, players, and dancers” contains everything but the kitchen sink. Bernstein took the Latin Tridentine Mass of the Roman Catholic Church and threw in new English texts by Stephen Schwartz (fresh off of “Godspell”), with contributions by Paul Simon and himself. The cast of more than 200 performers present music ranging from classical to Broadway to contemporary rock. President Richard Nixon, warned by the FBI that the notoriously leftist Bernstein was programming “coded anti-war messages” into the piece as part of a plot “to embarrass the United States government,” conspicuously boycotted the premiere.

Many questioned what a very secular Jewish composer like Bernstein could bring to the Catholic Mass (dedicated to the memory of the nation’s first Catholic president). The initial critical response to the “Mass” was decidedly mixed with conservatives like Harold C. Schonberg dismissing it as “fashionable kitsch,” but its reputation has risen over the years.

Bernstein’s “Mass” concerns the crisis of faith experienced by The Celebrant (the splendid baritone Nmon Ford), a young hippie preacher turned Catholic priest. The forces of Man and God are represented by an orchestra (the Mostly Mozart Orchestra led by Louis Langrée), an adult chorus (the Concert Chorale of New York led by James Bagwell), a children’s chorus (the Young People’s Chorus of New York City) with the spiritually conflicted congregation of Street Singers (a motley crew of classical and pop singers) backed up by a cadre of dancing Acolytes.

Elkhanah Pulitzer recreated her staging for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which expertly mixed groovy day-glo period elements with stark modernist elements that stood outside a specific time and place (the central white altar with neon cross designed and lit by Seth Reiser). Laurel Jenkins’ vernacular choreography had both dancers and singers boogieing down the aisles of David Geffen Hall.

The show begins with a dissonant pre-recorded “Kyrie Eleison.” Nmon Ford as The Celebrant enters in T-shirt and jeans with a guitar on his shoulder and sings “A Simple Song,” a plaintive folk prayer extolling simple faith that veers into rock in its second verse: “God loves all simple things; For God, is the simplest of all.” After this, The Celebrant dons increasingly blingy cassocks leading Latin choruses in a style influenced by Mahler but which also borrows heavily from the Bach Passions. The “rock” songs performed by the Street Singers challenge the orthodoxy with “Me Generation” philosophical tropes: “I believe in God, but does God believe in me?” The Celebrant suffers a crisis of faith brought on by the doubts of his followers and destroys the altar. But a child (the radiant voiced Tenzin Gund-Morrow) sings a reprise of “A Simple Song,” and The Celebrant’s faith is restored and the congregation comes together in harmony.

Bernstein’s evocation of Mahler sounds derivative, and his command of ‘70s rock and roll is not as idiomatic as his jazz and Broadway compositions. (Should he have farmed the rock music out to his literary collaborators Schwartz and Simon?) Somehow, Bernstein’s innate theatricality binds it all together along with his passionate commitment to his message. Ford’s Celebrant combined simple direct diction with a stirringly rich Verdian baritone voice that also could produce floating tenor sounds in the upper register (the role has been cast with both baritone and tenor voices). Ford never overpowered the music with operatic grandeur and added Gospel inflections where appropriate.

Langrée’s light and fleet conducting was characterized by transparent textures and constant forward motion that kept this unwieldy work from bogging down under the weight of its far flung ambitions and pretensions. Just keeping the enormous varied armies of performers on the same page is a great achievement in itself.

Is the “Mass” a dated artifact of its time? Is it a pretentious hodgepodge of derivative musical styles? I found myself deeply moved by it — the divided, disillusioned America that Bernstein viewed in 1971 with Watergate looming around the corner resonated with me in 2018. I was born into that America.

Also, Bernstein’s vision of The Celebrant trying to bring his divided congregation together in harmony spoke to me powerfully as a way forward into a better future. This text could have been written today or tomorrow: “O you people of power, your hour is now. You may plan to rule forever, but you never do somehow! So we wait in silent treason until reason is restored, and we wait for the season of the Word of the Lord. We await the season of the Word of the Lord.”

Word. Preach, Lenny.