The Up Stairs Lounge was a refuge and an unofficial community center for the LGBTQ community in New Orleans in the early 1970s. And a Sunday beer bust that featured “two hours of unlimited suds for one dollar” was “an irresistible affair for a certain cadre of gay men,” Robert W. Fieseler writes in “Tinderbox: The Untold Story of the Up Stairs Lounge Fire and the Rise of Gay Liberation.”

On June 24, 1973, an arsonist started a fire in the bar during the beer bust that killed 32 people and seriously injured another 15. As tragedies often do, the fire galvanized the nascent LGBTQ rights movement.

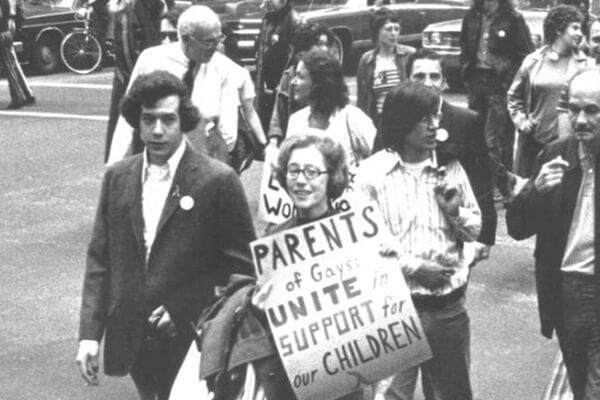

Vigils and memorial services were held across the country. Activists Morris Kight and Morty Manford launched what may be the community’s first national fundraising effort that gathered thousands of dollars for the victims. The Reverend Troy Perry, who five years earlier had founded the Metropolitan Community Church in Los Angeles and was already known nationally, was thrust into the spotlight because a number of victims, including Bill Larson, were members of the church’s New Orleans congregation. Larson was the congregation’s pastor and it sometimes used a part of the Up Stairs Lounge for services.

In a 1975 letter to other activists, Manford cited the 1972 organizing to develop and deliver a list of community demands to delegates at the Republican and Democratic National Conventions and the creation of the National New Orleans Memorial Fund in 1973 as efforts that “proved extremely useful in the struggle for our common goals.”

The incident, which remained the largest mass killing of LGBTQ people until a gunman murdered 49 people in a nightclub in Florida in 2016, has been largely forgotten in the community’s history. It was the subject of two earlier books and two documentaries, but Fieseler’s book is the first to place it in a national context and to describe the event’s role in building a national LGBTQ movement.

“This was the first nationally released piece,” Fieseler told Gay City News. “There was some amount of scholarship.”

The book was published in hardcover in 2018 and the paperback edition was released on June 4. It won the 2019 Edgar Award in Best Fact Crime, and Fieseler received the 2019 Lambda Literary Judith A. Markowitz Award for Emerging LGBTQ Writers on June 3. “Tinderbox” was a finalist for Lambda’s 2019 Randy Shilts Award for Gay Nonfiction.

The book opens with a lengthy section that introduces the people who were in the bar during the fire or had friends, family, or partners who were there. Fieseler describes an LGBTQ community that had made a kind of peace with New Orleans. We meet the man who was suspected of setting the blaze, Rodger Dale Nunez, who committed suicide in 1974. Fieseler’s description of the fire, or “nineteen minutes of hell,” and what occurred in the aftermath are difficult to read.

The fire initially received national attention, but once it became known that the Up Stairs Lounge served an LGBTQ clientele, the amount of media coverage and any sympathy for the victims outside of the LGBTQ community declined.

“It’s a piece of history that has all these emotional notes,” Fieseler said. “Where the stories drop off is when the nature of the bar and the nature of who died became known.”

There was also some resistance within the New Orleans LGBTQ community to outside interest.

Perry was perceived by some in New Orleans as an interloper who was “not helpful and was just going to raise a lot of problems for local gays,” Fieseler quotes one man saying in an encounter with the pastor in a New Orleans bar.

But there were also moments of bravery and generosity.

Clay Shaw, “the most famous homosexual in New Orleans” and a successful businessman who had been accused, but acquitted in 1969 of plotting to assassinate President John F. Kennedy, offered Perry a street near the lounge for a memorial service after several New Orleans denominations would not let Perry hold a service in their churches. The offer was “professionally dicey” and a “political risk,” Fieseler writes.

A United Methodist congregation eventually allowed the service to be held in its church. The five white women who made up the Board of Elders supported Reverend Edward Kennedy, their African-American pastor, and “flouted decrees” in United Methodist doctrine saying that homosexuality was “incompatible with Christian teaching,” Fieseler writes.

As the service neared the end, Perry told the mourners that media, including television news crews with cameras, were outside the church. After some discussion about exiting through a side door to avoid the press, a “butch-looking woman” said, “I came in through the front door, and I’m damn well going out that way,” Fieseler writes.

Though many of those who attended the service were closeted, they stood together and left by the front door. If there had been TV cameras outside the church, they were gone by the time the crowd left the service.

“It was an enormously brave thing to do,” Fieseler said. “I feel like it was a transformative moment.”

After his extensive research and interviews in New Orleans, Fieseler, who was raised near Chicago and lived in Boston for some time, has moved to the city with his husband.

“Culturally, it got into my pores,” he said. “It’s a real urban landscape. Parts of it are quite dangerous, parts of it are quite fun… The soul of the place is still alive.”

TINDERBOX: THE UNTOLD STORY OF THE UP STAIRS LOUNGE FIRE AND THE RISE OF GAY LIBERATION | By Robert W. Fieseler | W.W. Norton & Company | $16.95 | 384 pages