During a lecture at Florida’s Jacksonville University just days before the 2016 presidential election, Amy Coney Barrett, who was then a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, argued that Obergefell v. Hodges, the landmark Supreme Court ruling from the year before that acknowledged the right of same-sex couples to marry, was misunderstood by the public.

The question, she asserted, was not who was in favor of marriage equality and who was opposed, but rather “who gets to decide” — the courts or the legislative branch of the government.

The public’s confusion about what happened on June 26, 2015, Barrett asserted, was a “New York Times headline problem.”

In remarks largely focused on the late Justice Antonin Scalia, for whom she had clerked in the late 1990s and whom she revered, Obergefell was a classic example, in Barrett’s view, of how the liberal wing of the Supreme Court had taken the concept of “substantive due process” rights under the 14th Amendment far beyond where “originalists” like Scalia believed was merited.

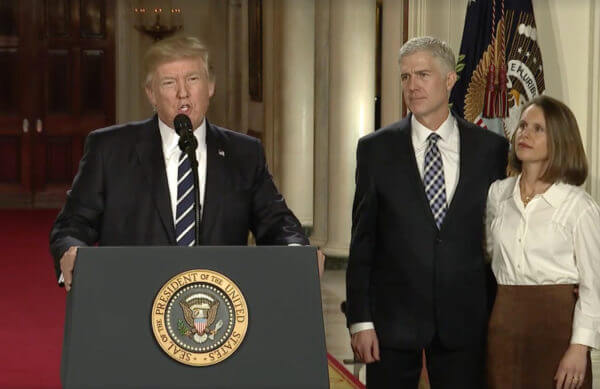

Trump’s Supreme Court choice would move the high court sharply to the right

While Scalia believed that both constitutional and statutory language must be interpreted based on the original text and meaning of the words when written, justices embracing “substantive due process” allow the high court to say “for itself what it thinks those rights are, based on what it thinks contemporary values are at the time,” Barrett told her audience.

At the conclusion of her talk in Jacksonville, Barrett — whom President Donald Trump announced September 26 as his choice to fill the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s seat on the Supreme Court — said that in looking at the presidential election the following week, “The who decides question is a really important question to me.” She added that she worried “about my voice being taken away.”

Just what was Barrett’s voice on marriage equality?

An October 2015 open letter, to which she was among nearly 1,400 Catholic women signatories, stated that “marriage and family founded on the indissoluble commitment of a man and a woman — provide a sure guide to the Christian life, promote women’s flourishing, and serve to protect the poor and most vulnerable among us.”

Signing this letter three months after the high court had ruled that the Constitution guarantees the rights of same-sex couples to marry is clearly an indication that Barrett felt that, at least on the issue of marriage equality, her voice had been taken away.

The letter was posted on the website of the Ethics & Public Policy Center (EPPC), an interdenominational group based in Washington that touts itself as “defending American ideals” and has strong support among leading conservatives.

Barrett’s affiliation with the EPPC is not her only link to religious conservatives. She is also a member of People of Praise, a South Bend, Indiana-based group of Christians that grew out of the Catholic Charismatic Renewal, which in the 1960s emphasized tradition in reaction to some of the liberalizing that took hold in the Church during that decade. People of Praise emphasizes strict gender roles, and for a time women in the group were labeled “handmaids,” a fact that has led some Barrett critics to simplistically tie her faith practice to the dystopian world described in Margaret Atwood’s 1985 novel “The Handmaid’s Tale.”

A deep dive into Barrett’s faith practices, however, is not necessary to raise alarms about the policy implications of her ties to the religious right. In 2017, when Barrett won her seat on the Chicago-based Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, Lambda Legal cited a lecture she delivered that was paid for by the Alliance Defending Freedom, a litigation group that doggedly fights LGBTQ advances in federal and state courts nationwide.

In a release this past week, the Human Rights Campaign charged that Barrett’s remarks at Jacksonville University amounted to a defense of those Supreme Court justices who dissented in the Obergefell marriage equality case.

HRC also noted that, in the same lecture, she challenged the Obama administration’s conclusion that Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments, which prohibits sex discrimination in schools receiving federal funding, requires that the gender identity of transgender students be respected.

“It does seem to strain the text of that statute to say that Title IX demands” that policy position, Barrett said.

In talking about the issue, she seemed insistent on misgendering transgender students who have claimed Title IX protections, referring to them several times as “someone who was physiologically a boy but identifying as a girl.”

Barrett’s views on Title IX have since been severely undermined by the Supreme Court, which in its June ruling in the Bostock case, found that employment discrimination based on gender identity and sexual orientation is prohibited sex discrimination under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Interpretations of other federal nondiscrimination laws — in areas like housing, public accommodations, and education — typically rely on the high court’s view of Title VII, but even though federal courts have begun to do exactly that, the question of the breadth of the Bostock ruling has not yet been decided by the high court.

If confirmed by the Senate, Barrett would likely be among the conservative votes on that issue.

In predicting back in 2016 what would be big issues to come before the Supreme Court, Barrett mentioned not only Title IX but also religious exemptions.

In fact, the day after the presidential election, the Supreme Court will review a Third Circuit Court of Appeals ruling that rejected claims by the Catholic Social Services agency in Philadelphia that lost its foster care services contract with the city by refusing to work with same-sex couples. The Third Circuit, relied heavily on a 1990 decision, authored, ironically, by Scalia, that found there is no religious exemption from neutral laws of general application even if they incidentally impact somebody’s free exercise of religion.

If that precedent were overridden the door would be open to all manner of claims of religious opt-outs from nondiscrimination laws protecting the LGBTQ community.

Concern about how Barrett would react to the Catholic Social Services appeal assuming she were on the court by November 4, as Senate Republicans hope, is based in part on her stated views on the doctrine of stare decisis — the tradition by which the high court stands by its earlier precedents in the absence of “special justification” or “strong grounds.” In the past, including in Jacksonville, Barrett has suggested that stare decisis need not constrain the court, that it is more “a matter of policy,” rather than a “mandate.”

In 2017, Lambda noted that Barrett declined to say whether Obergefell qualified as a precedent that could not be overturned.

The precedent that creates the biggest concern among Barrett critics, however, is Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that found a constitutional right to abortion.

In her Jacksonville lecture, she suggested that “the core” of that ruling was unlikely to be overturned in the future, but said the Supreme Court would likely be amenable to greater restrictions on abortion access.

But in a 2003 law journal article, Barrett clearly suggested that Roe was “an erroneous decision,” that might be ripe for reconsideration by the Supreme Court.

The one thing her supporters and her opponents seem to agree on is that she would be an anti-Roe vote.

CNN’s Manu Raju tweeted that Missouri Republican Senator Josh Hawley, who has predicated his support for a high court nominee on their view that Roe was “wrongly decided,” told him, “As to the question on Roe — yes, I think she meets that standard.”

Meanwhile, in a joint statement opposing Barrett’s nomination, People for the American Way, Alliance for Justice, the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, and the National Women’s Law Center, emphasized “the importance of opposing any nominee who will gut and overturn Roe. v. Wade.”

Those groups along with HRC and Lambda Legal also pointed to the dangers Barrett’s nomination to the high court posed to the survival of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The Obama administration’s signature healthcare achievement once again goes before the high court in November.

In a 2017 law journal article, Barrett quoted Scalia’s critique of the two cases in which the high court upheld the ACA, saying it should be re-dubbed SCOTUSCare. Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2012 opinion that found the law’s individual mandate constitutional as an appropriate use of Congress’ taxing authority, she argued, pushed its text “beyond its plausible meaning to save the statute.”

Concluding its critique of Barrett’s nomination, HRC wrote, “Her hostility towards many of society’s most marginalized, victimized, and vulnerable groups raises serious concerns about her ability to be impartial and fairly consider the rights of all who come before the Court, including LGBTQ people.”

To sign up for the Gay City News email newsletter, visit gaycitynews.com/newsletter.