Depression-era play about interracial gay love on the farm stretches credulity

If good intentions were enough to make a hit show, the ticket line for “Sacrifice to Eros” would be blocks long.

Frederick Timm’s earnest Depression-era re-telling of the Biblical story of the prodigal son, with a Pollyanna-ish gay twist, is a refreshing example of playwriting with a heart.

But its well-meaning morality tale is a story better suited for a church basement than a New York City stage. You almost feel guilty pointing out that this kindly show with a cautionary message for gay men is a giant mess from the beginning.

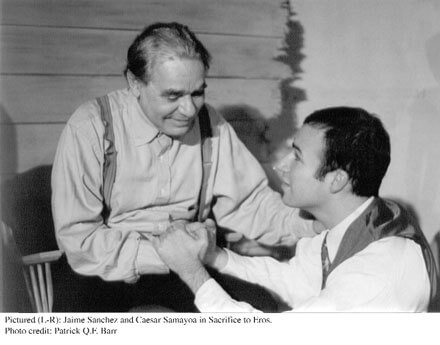

The show tells the story of the Westfield family and their Wisconsin farmhouse. Rita (Maria Helan Checa), the mother, and Cliff (Don Clark Williams), the father, and crazy Aunt Edna (Pamela Dunlap) nervously await a decision by dying patriarch Papa Westfield (Jaime Sanchez) on the future of their farm, which Cliff says is “full of heartache, memories, and ghosts.”

The family also anticipates the homecoming of Jesse (Caesar Samayoa), Cliff’s brother who moved to Chicago after having an affair with Tom (Eric Jordan Young), their neighbor, who is now a married father.

Jesse’s return kicks into motion a series of gay-positive revelations that bring lingering anger and disappointments to a boiling point. Will Jesse stay on the farm and help his family or return to Chicago, where he’s been living an openly gay life? Will Tom rekindle his relationship with Jesse? It gives nothing away to say the answers are more smiles than sorrows.

Timm, whose other works include “Accord of Angels” and “Harvest of Strangers,” writes with a sensitive pen. But the list of texts and themes he references—from “The Grapes of Wrath” to “King Lear” to the Bible’s fraternal tales of Jacob and Esau and Cain and Abe—and the wordy way he propels a narrative is disorienting. His script is far too realistic and overwritten to be parabolic.

What’s most puzzling is the show’s message. Timm seems to suggest that gay men should re-evaluate the promiscuity and party life of the city in favor of—what? Moving to a farm? He’s written an indictment of a gay culture that teems with wish fulfillment, without offering any meaningful alternatives.

“Sacrifice to Eros” marks the debut of Common Ground Productions, a company whose feel-good name reflects, as outlined in the program notes, its commitment to “breaking racial, ethnic and sexual stereotypes [via] non-traditional, color-blind casting.”

It’s a tricky thing to pull off without compromising textual integrity. Shakespeare is one of the few playwrights whose work begs for racial and gender tinkering.

But in this case the experiment goes awry. It doesn’t help that no one in the racially mixed African-American, Latino, and Caucasian cast looks remotely alike; believing they’re somehow related is a chore. That the Klan hasn’t killed every member of this family and burned down their house and barn is a miracle of playwriting naiveté.

Although it seems fresh to contemporary eyes, you have to seriously suspend disbelief when an interracial couple tending a farm in the rural Midwest during the Depression suddenly supports gay relationships. Decades worth of therapy apparently happened overnight.

And making an openly gay interracial couple the heart of this play, complete with make-out sessions on the front porch, throws the show over the boundary of racial and sexual experimentation into ridiculousness. Is this Wisconsin or West Hollywood?

The cast’s abilities vary wildly under Marc Parees’ unsteady direction. Checa and Williams call in their performances, while Sanchez, overacting with the eyes of a madman, uses a bullhorn.

As the gay couple, Young (who played Billy Flynn in “Chicago”) and Samayoa are physically mismatched, but find some moments of tenderness amid Timm’s syrupy prose. (“It seems like I’m finally saying yes to belonging,” Jesse says.)

Dunlap is delightful as Aunt Edna. This emotionally intuitive actress, who can say volumes with her eyes, gives a kooky, sensitive performance that seems out of place in this fumbling play, as if she mistakenly wandered on stage from an unseen Horton Foote drama playing next door (her uncredited costume, however, makes her look like an overworked librarian, not a farm dweller).

Set designer Sean Richards has constructed a handsome, chewed-away front porch that fits nicely on the cramped Pantheon Theatre stage. But placing a flower garden downstage left, out of view of anyone not seated in the front row, makes no sense for an area that plays such a crucial role in the show.

But that’s the least of the show’s woes. A failed attempt at colorblind casting, myriad issues not addressed in interesting ways, moral finger-wagging, and a mostly lackluster cast ultimately make this show far too easy to sacrifice.