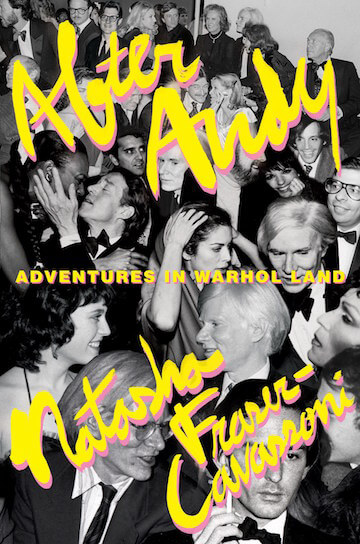

PENGUIN RANDOM HOUSE

“I liked Andy immediately because I felt he was very accessible,” Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni recently said as she was promoting her new book “After Andy: Adventures in Warhol Land,” according to a profile in Vanity Fair. “Andy had an extraordinary magnetism. He was kind of an amoeba or Zelig-like. When people say he was negative, I totally disagree, it’s what you brought.”

The daughter of Lady Antonia Fraser and the stepdaughter of Harold Pinter, Fraser-Cavassoni “brought” what so many well-heeled, quick-witted, good-looking women — “Baby” Jane Holzer, Susan “Viva” Hoffmann, and, most iconic of all, Edie Sedgwick — did during the three decades he ruled the world as an innately passive yet sublimely benevolent cultural despot.

Sedgwick became the most famous — even though the films he made with her haven’t been publically exhibited for years. She’s exceptionally lively in them. And it’s typical of Andy that he decided to call a proposed (but never made) sequel to the best of them, “Beauty #2, Isn’t It Pretty To Think So”— borrowing the last line of Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises.”

Continued fascination with Warhol emphasize his likability and a sexual side long laughed off

Fraser-Cavassoni knew Andy in the 1980s, having drifted into his orbit almost automatically from the world of fashion, where she commingled with the likes of Karl Lagerfeld and Yves Saint-Laurent. Her view of Andy is as one with that of actress Mary Woronov, who once observed to me that “Andy was never not nice.”

I never saw him otherwise. I knew him from the mid-‘60s, when I was heavily involved in the avant-garde film scene as a critic and commentator. The experimental filmmakers Gregory Markopoulos and Jack Smith (both of whom I also knew) were Andy acolytes. I liked Andy for the same reasons Fraser-Cavassoni did. And while the periods we spent time with him were different, Andy, at heart, remained very much the same — invariably alert, wildly playful, and uncannily witty.

If New York in the mid-‘60s had a “headquarters” it was Andy’s Silver Factory. This ramshackle studio-cum-salon located on the fifth floor of an otherwise empty building at 231 East 47th Street that used to house a sewing machine factory, was a beehive of activity. Andy rented it for a mere $100 a year. It was there, from roughly 1964 through 1967, that Andy and his assistants, photographer Billy Name (aka Billy Linich) and poet Gerard Malanga, made his paintings and shot his early silent portrait films, plus a number of sound ones (“Harlot,” “Vinyl,” and “Horse” being among the most memorable), until he turned filmmaking duties completely over to collaborator Paul Morrissey.

Then came the June 3, 1968 attempt made on his life, when a disgruntled would-be writer and actress named Valerie Solanas stormed into Andy’s new HQ — the Office — located at 33 Union Square West. Solanas claimed her motivation was because Andy “had too much control over my life.” But for those of us who knew him, this was clearly a projection of her paranoia-addled brain. Andy never forced anyone to do anything, but was instead invariably encouraging of the artistic aspirations of those who came into his orbit. He was as reluctant to discard people as he was the items both valuable and valueless — everything from antique cookie jars to buttons that had fallen off — he hoarded with confounding zeal. And this was why he was to some degree reluctant to give Valerie the boot.

Solanas had a script entitled “Up Your Ass” that she wanted Andy to — nay, insisted that he — film. This he didn’t do, but he gave her a featured a role in “I, a Man” (1967), in which she speaks at some length to the film’s star Tom Baker while they stand in the Silver Factory stairwell. She also made a non-speaking appearance in his “Bike Boy” the same year. Apparently this didn’t placate her. The gunshot wounds she inflicted caused Andy considerable physical suffering. He nearly died in the emergency room, had several operations subsequent to that, and when he finally expired 19 years later it was in the wake of a gall bladder operation performed to repair tissue destroyed in the shooting.

In some ways Andy’s demise was predictable — Solanas or not. He wasn’t made of the stuff that would guarantee a long life. Born to abject poverty in Pittsburgh in 1928, he was the youngest of Andrej and Julia Warhola’s four children. A sickly child, Andy suffered from St. Vitus’ dance and scarlet fever — the latter responsible for his pale pink blotched complexion. Close to his mother from the start (she gave him coloring books and crayons when he was sick in bed — which was quite frequent), he grew even closer to her when his father died when Andy was just 13.

His plans for a career as a commercial artist, however, took him to New York. As soon as he achieved some level of success, he sent for his mother to live with him. He accompanied her to church every day, and she kept his townhouse tidy and didn’t interfere with his private life. Andy adored Julia’s handwriting and used her to inscribe the descriptive copy for his illustrations.

Andy first hit it big designing shoe illustrations for “I. Miller,” creating whimsical drawings befitting the foot fetishist he was. His cat drawings were turned into art books and sold at the east side confectionery Serendipity III. More profitably, Andy designed display windows for New York department stores including Bloomingdales. So did Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. But those artists were ashamed of the work they did for money, while Andy was proud of it. Rauschenberg and Johns, lovers for so many years, were also closeted. Butch in manner, they were able to more or less pass as straight, something easy to do at a time when so much as mentioning homosexuality was verboten in polite conversation.

Though Andy did not share his fellow artists’ adeptness at butchness — nor any inclination to pursue it — he found freedom in the prevailing silence about gay life. He was fascinated by the infamously seductive photograph of Truman Capote that adorned the dust jacket of his first novel, “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” in 1948, enormously encouraged that someone so swish could make it big. He wrote Capote constantly — getting no reply. But he didn’t hold grudges. Year later, when Capote’s career hit the skids — thanks to “La Cote Basque,” the disastrous Esquire preview of his scandalous unfinished high society tell-all “Answered Prayers” — Andy encouraged Truman to write pieces for Interview magazine, his lively publication devoted to film, fashion, and celebrity.

By the time of Interview’s arrival in 1969, Andy was running with the swells. A child of the Depression, in time he became among the first of the prominent Reagan Democrats — going so far as to put Nancy Reagan on Interview’s cover and frugging the night away at Studio 54 with Roy Cohn.

Clearly, Andy’s bohemians and marginals vanished with the report of Solanas’ gun and he was taking cover with the powerful who, thanks to his artistic fame, were now at his feet.

Even had Solanas not struck, the Silver Factory couldn’t have gone on forever. She wasn’t the first woman to threaten Andy with a gun, and she was far from the only unstable character to cross his path. Dancer Freddie Herko and actress Andrea Feldman both jumped out of windows to their death (in 1964 and 1972, respectively). And thanks to amphetamine addiction coupled with a shaky psychiatric history (she was in and out of New Canaan, Connecticut’s Silver Hill treatment facility several times in her brief life), Sedgwick possessed, along with her wit and beauty, an emotional fragility common to many in Andyland.

Speaking to the Sunday Herald Tribune about his 1965 film “Suicide,” Andy said of one particular marginal: “‘I found this person, my star, who has 13 scars on one wrist and 15 scars on the wrist from suicide attempts. He has marvelous wrists. The scars are all different shades of purple. This was my first color movie. We just focused the camera on his wrists and he pointed to each scar and told its history, like when he did it, and why, and what happened afterward.”

The name of that “star” was Roq — a French-Canadian character who showed up at the Silver Factory one day and immediately began to talk about himself. As Andy was busy with his “Flowers” painting series, I sat and listened to Roq, who spoke of his many sanitarium stays while showing me the slashes on his wrist. He even claimed that at one institution Audrey Hepburn — supposedly as suicide-prone as he was — was there too.

Capable of multi-tasking long before the term came into fashion, Andy announced then and there he would make a film about him. It was a sound film (perhaps his first in color) that consisted of a close-up of Roq’s wrist as he spoke off-screen of why and how each slash was made. Like so many of Andy’s films, “Suicide” was never publically exhibited and resides in the vaults of the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. But its making clearly demonstrates Andy’s amazing ability to conceive and execute projects at the drop of the proverbial hat. That was but one example of his keen mind.

Over that period in the ‘60s, I saw Andy many times outside of the Factory — at avant-garde film screenings, the New York Film Festival, art receptions, and the like. He always remembered exactly what we had been talking about the last time we met — something precious few are capable of doing. Alas, after the shooting I never saw him again. But following his activities in the last 19 years of his life it was clear his smarts hadn’t suffered. And that’s because he was one sassy gay man.

In the face of all that befell him, good and bad, Andy’s primary defense was his gay street wit — a trait he recognized in others and utilized whenever possible (most famously with Ondine in both “Chelsea Girls” and his tape-recorded novel entitled “A”). “I look like a Dior dress” he said of his post-shooting body. In the “The Andy Warhol Diaries” (transcripts of conversations with collaborator Pat Hackett made to take account of his everyday expenses for tax purposes, later redacted and published posthumously), he observed, “Ran into [poet] Rene Ricard who’s the George Sanders of the Lower East Side — he was with some Puerto Rican boyfriend with a name like a cigarette.”

Andy played the naif to the press, but he was sharp as a tack. He spotted David Hampton — the grifter who claimed to be the son of Sidney Poitier and was the subject of John Guare’s play “Six Degrees of Separation”) — as the phony that he was the moment he came by to get his foot in the Warhol door. “Everybody at the office, they all believed it,” he noted, Andy’s boyfriend Jed Johnson included.

It will be interesting to see how Johnson and his identical twin brother Jay figure in art critic Blake Gopnik’s recently promised exposé of Andy’s sex life — set for publication next year. Back in 1971, journalist John Wilcock wrote a volume he called “The Autobiography and Sex Life of Andy Warhol,” which consisted of short pieces about Andy and his collaborators but next to nothing about his sex life — the joke being that Andy was far too asexual for anything.

The truth is, of course, quite different. Poet John Giorno, of Warhol’s “Sleep” (1963) fame, was an Andy boyfriend, as was Silver Factory major domo Billy Name, Philip Fagan (whom, according to film scholar Callie Angell, Andy took more silent film portraits of than any other person), and Danny Williams, who created the light shows for the seminal “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” shows

As the 2007 documentary “A Walk into the Sea” reveals, Danny (who styled himself to look like a younger, prettier Andy) was the only other person Andy allowed to use his 16mm camera. An amphetamine addict, he became what Mary Woronov called “one the Mole People” before leaving the Factory, returning home, and drowning himself. There was a sad end for Andy’s last love, Paramount studios executive Jon Gould as well — AIDS.

As for Andy’s expiration date, February 22, 1987, I prefer to think of him departing this mortal coil right after the last entry in “The Diaries” on February 16. It was a note about Brigid Berlin (the only Silver Factory veteran to make the transition to the Office) announcing she was going to a “fat farm” in London: “She charges $2,000 for each sweater she knits at the reception desk, while she’s supposed to be answering the phones, and she’s selling so many of them — Paige [Powell, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s girlfriend] even bought one.”

Was Andy buried in one of Brigid’s sweaters? Isn’t it pretty to think so?

AFTER ANDY: ADVENTURES IN WARHOL LAND | By Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni| Penguin Random House | $28 | 336 pages