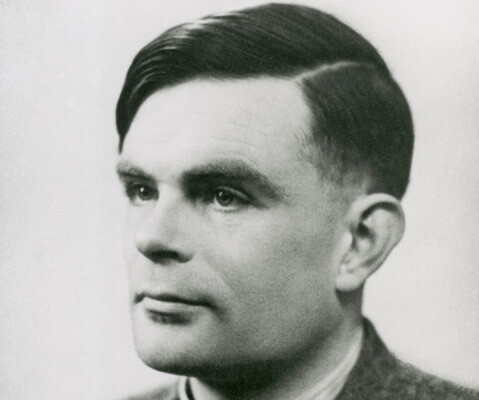

Alan Turing in 1951. | NPL ARCHIVE, SCIENCE MUSEUM / LONDON

June 23 marked the centenary of the birth of Alan Turing, the queer British mathematical genius and philosopher considered the father of the modern computer, the World War II hero who did as much as Winston Churchill to keep Britain alive and fighting in the war’s early years by cracking the secret of Nazi Germany’s communications codes, and an unapologetic gay man who was ahead of his time because he believed that homosexuality was a normal form of love. On that last score, he was persecuted and tortured by the British government for being queer.

The story of Turing and his seminal role in defeating Hitler’s fascism was hushed up after his death from cyanide poisoning at the age of 42 in 1954 –– in what a coroner’s inquest ruled a suicide –– by a combination of British homophobia and the UK’s Official Secrets Act, a stringent form of censorship that prevented publication of anything the government deemed critical to national security.

It was not until 1973 that a statement from a group of gay mathematicians associated with Britain’s Gay Liberation Front at long last lifted the veil of secrecy on Turing’s unrivaled wartime contribution and told the public how the government had arrested the queer genius under the insane 1885 Labouchere Amendment that had sent Oscar Wilde to hard labor in prison. The arrest forced Turing to choose between sharing Wilde’s fate or chemical castration designed to make him asexual. Opting for the second course as the lesser of two evils, Turning endured a series of estrogen injections that made him grow breasts and left him impotent.

Turing’s story has since often been recounted, notably in a hit 1986 play, “Breaking the Code,” by British playwright Hugh Whitemore, which had a long run on both the London stage and on Broadway starring Sir Derek Jacobi in a magnificent performance that won him a Tony Award nomination. In 1997, the BBC turned this play into a memorable film, aired in the US on PBS’s “Masterpiece Theater,” with Jacobi recreating his role as Turing.

The play and film were based on a superb biography of Turing, “Alan Turing: The Enigma,” by the British writer Andrew Hodges, and portrayed Turing, who continued to be hounded by the police until his death, as having taken his own life by eating an apple poisoned with cyanide. (The Apple Computer logo, showing an apple with a bite taken out of it, is said to be a thinly-veiled tribute to Turing.) This version of Turing’s supposed suicide has been widely unchallenged — until now.

Just as commemorations of the war hero’s centenary were taking place all over the UK, a paper challenging the inquest verdict of suicide, terming it “not supportable,” has been published by one of the world’s leading experts on Turing, Professor Jack Copeland of the University of Canterbury at Christchurch, New Zealand. (A pdf version of Copeland’s paper automatically downloads at tinyurl.com/dxsh64q.) Copeland’s work could well lead to a wholesale revision of an important chapter in gay history.

First, let us consider the many unique contributions Turing made to computer science and the Allied victory in World War II.

Turing was only 24 and still a student at Cambridge University when he wrote a paper proposing the possibility of “a machine that thinks” — in what was nothing less than a blueprint for the modern computer. Gay novelist David Leavitt, author of a serviceable 2006 Turing biography written from a gay liberationist perspective, “The Man Who Knew Too Much: Alan Turing and the Invention of the Computer,” wrote that his “universal machine” was capable of performing “the work of an infinity of single-use machines,” on June 22in the Washington Post article. Leavitt’s Post article was one of few published in the US so far about the great man’s centenary. The computer he designed became known as “Turing’s machine.”

On the very first day of World War II in September, 1939, having been recruited by Britain’s intelligence services, Turing took up residence at the now-famous Bletchley Park, the sprawling Gothic Victorian mansion and estate that served as the wartime headquarters for Britain’s top codebreakers.

The key assignment for Turing and his colleagues in Hut 8 at Bletchley Park was to crack Enigma, the Nazis’ cipher machine that Hitler’s forces used to encode all their communications. Fighting the Nazis’ machine with one of his own, Turing led in creating a codebreaking computer known as Victory, but more familiarly referred to as “the bombe” by Hut 8’s mathematical denizens.

“Turing’s bombes turned Bletchley Park into a codebreaking factory,” Copeland wrote in one of seven articles commissioned by the BBC to commemorate the centenary. “As early as 1943 Turing’s machine was cracking a staggering total of 84,000 Enigma messages each month –– two messages every minute. Turing personally broke the form of Enigma that was used by the [Nazi] U-boats preying on the North Atlantic convoys” of arms, food, and raw war materials from the US to Britain, without which a starving Britain could not have survived.

Turing next devised a way to crack a new and much more sophisticated Nazi cipher machine, which the British code-named Tunny, a teleprinter communications network that connected the German military’s high command in Berlin to the frontline troops in Europe and North Africa.

The method of cracking the Tunny messages, known at Bletchley Park as “Turingery,” “gave detailed knowledge of German strategy — information that changed the course of the war,” according to Copeland’s BBC article, which cited military historians as saying that “Turingery” and his three “strokes of genius” –– creating the bombe, cracking the U-boat Enigma, and breaking the Tunny code –– “shortened the war by as many as two to four years.”

A “conservative estimate,” noted Copeland, put at seven million the number of deaths for each year the war continued, and if Turing had not broken the codes and the war had continued for another two to three years, “a further 14 to 21 million people might have been killed.”

With so many lives saved by Turing’s work, not to mention his role in preserving the island kingdom from a Nazi invasion, it is nothing less than hallucinatory to consider how Britain put this genius through the torture of chemical castration.

But Turing, who had known he was gay from very early in his childhood and saw nothing wrong in it, had the misfortune to be arrested for homosexuality in 1953, at the height of the Cold War in the midst of what British queers called the Great Purge –– a massive police crackdown on homosexuals in which nearly 5,000 were arrested in a matter of months on charges either of “gross indecency” (the same law under which Oscar Wilde was imprisoned), solicitation, or sodomy. This represented an increase of 850 per cent over the arrest rate for homosexuality in 1938, just before World War II.

The Great Purge was provoked by the defection of diplomats Guy Burgess, a notorious homosexual, and Donald Maclean to Moscow, and in the climate of the day homosexuality was virtually equated with treason in the minds of the police. (See this reporter’s September 6, 2007 article, “Free the Buggers,” available in the gaycitynews.com pre-May 2012 archives.)

By the time of his arrest, it had been a year since Turing’s government career cratered when he lost his security clearance because he was a homosexual — something he never took any pains to conceal throughout his life. Having secured a teaching post at the University of Manchester, he was having what Leavitt tactfully calls a “businesslike relationship” with a young Manchester man, who he discovered had stolen a significant amount of money from him. Under questioning from police when he reported the theft, Turing responded, with his typical frankness, that he’d been sleeping with the young man, and found himself arrested. He was forced to undergo year-long treatments that killed his sex life and remained under tight police surveillance until his death.

Turing had always been fascinated by the story of the poisoned apple in his favorite movie, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” a fact that buttressed the standard account of his suicide.

But now, Copeland’s new paper suggests that homophobia may have influenced the verdict of the coroner, who ruled that Turing took his own life “while the balance of his mind was disturbed.” Relying on popular prejudices toward homosexuals, the coroner added, “In a man of his type one never knows what his mental processes are going to do next.”

The police never tested the half-eaten apple found next to Turing for cyanide.

Copeland has unearthed testimony from friends about Turing’s good humor in the days preceding his death. A neighbor described him as throwing “such a jolly tea party” for her and her son four days before he died. And his close friend Robin Gandy, who had stayed with him the weekend before, said that Turing “seemed, if anything, happier than usual.”

Copeland gives credence to Turing’s mother’s theory that his death was accidental. Turing had cyanide in his house for chemical experiments he conducted in his tiny spare room — the “nightmare room” as he dubbed it. He had been electrolysing solutions of the poison and electroplating spoons with gold, a process that requires cyanide. He was also known for his habit of tasting chemicals to determine what they were. Copeland also notes that he could have inhaled the fumes from the bubbling cyanide, which act much slower in causing death than ingestion, giving him time to retire to bed before they killed him.

But it’s not too paranoid to imagine yet another possibility mentioned by Copeland. With the discovery of the Cambridge Five Soviet spy ring headed by the well-known homosexual Sir Anthony Blunt and the defection of Burgess and Maclean, the “Queer = Red” equation was so prevalent in the British Cold War etabllishment that MI5, the British secret intelligence service, could well have decided simply to eliminate Turing before he could be tempted to pass on sensitive intelligence and computer progress to Moscow. Assassinations by MI5 were hardly unknown, as an extensive spy literature by former service members –– historians and novelists such as John le Carré and Ian Fleming alike –– suggests.

In 2009, after an extensive Internet campaign by admirers of Turing, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown made a formal public apology for the way the British government treated the queer genius, paying tribute to him as “one of those individuals whose unique contribution helped to turn the tide of war.” He was sickened, the prime minister acknowledged, by “the appalling way he was treated.” That included killing Turing off in history by covering up his war-time role for decades.

If Copeland is right that we may never know for sure just how Turing died, one thing is certain –– not enough attention is being paid to his centenary in this country, despite the fact that his work saved countless American as well as British lives. Why, for example, has PBS not rescheduled a re-airing of “Breaking the Code”? For that matter, why haven’t the vulgarians who run Logo found airtime to show this film, preferring to offer us the umpteenth reruns of drag makeup tips from RuPaul? And why is Turing’s exemplary life, which he lived as an openly gay man without fear, not getting any attention in our gay press? Our youth could certainly benefit from such a heroic and brilliant role model.

An extensive and excellent website on Alan Turing is maintained by his biographer Anthony Hodges at www.turing.org.uk/turing/. “Breaking the Code,” starring Sir Derek Jacobi, are readily available from Amazon.com, as are the Hodges and Leavitt biographies. See also a fine article by Pamela McCorduck, “Alan Turing Saved My Life” in the June issue of the Atlantic at tinyurl.com/co4w3b8.