This year, the National AIDS Memorial, in partnership with the Southern AIDS Coalition and Gilead Sciences, Inc., took on the South’s HIV/AIDS epidemic with its “Change the Pattern” campaign.

“It’s still 1987,” said Jada Harris, a straight Black ally who is the program manager for the National AIDS Memorial’s “Call My Name” Quilt program. “We still in a state of emergency, even though there is advanced treatment available and people are living longer.”

According to the National AIDS Memorial, in 2020, the South comprised 38% of the US population but represented over half of new HIV diagnoses. That is the highest rate in the US, reported PBS, which aired a documentary called “Wilhemina’s War” about one woman’s fight in South Carolina in 2016 to save her family members living with HIV.

HIV.gov reported in 2019 that Black and Latinx communities are disproportionately affected by HIV compared to other racial and ethnic communities. Black people represented 13% of the US population, but 40% of people with HIV, and Latinx communities represented 18.5% of the population, but 25% of people with HIV. The agency found that gay and bisexual men accounted for about 66% of new infections each year, even though they make up only 2% of the population, with the highest burden among Black and Latino gay and bisexual men. While there are more than 1 million people who identify as transgender in the US, adult and adolescent transgender people made up 2% of new HIV diagnoses in the United States and dependent areas. Most of those new HIV diagnoses were among Black people.

HIV.gov also found Black women are also disproportionately affected by HIV as compared to women of other races or ethnicities. Although annual HIV infections remained stable overall among Black women from 2015 to 2019, the rate of new HIV infections among Black women is 11 times that of white women and four times that of Latina women.

HIV.gov stated that effective prevention and treatment are not adequately reaching people who could benefit the most.

“It’s still very much a health crisis in the South,” Harris said. “A lot of that has to do with access to education.”

Earlier this year, Gilead funded the AIDS Quilt’s return to San Francisco for a massive display in Golden Gate’s Robin Williams Meadow for its 35th anniversary, said Kevin Herglotz, chief operating officer at the National AIDS Memorial.

He praised Gilead for its commitment, allowing the National AIDS Memorial “to be able to go out there and do this powerful work. That’s important work.”

Changing the pattern

The Change the Pattern campaign is one of the large campaigns Gilead Science has spearheaded with HIV/AIDS organizations to combat the epidemic since the beginning of 2021.

Change the Pattern is part of the $2.4 million grant from Gilead awarded to the National AIDS Memorial in 2019. The grant supported bringing more than 50,000 panels of the Quilt back to San Francisco permanently from Atlanta, where it had found a home for 22 years, and to support traveling displays of the Quilt and educational campaigns, Herglotz said.

He added that some of the funding also helped grant 17 new scholars $5,000 each through the Pedro Zamora Young Leaders Scholarship this academic year.

The Change the Pattern campaign has also worked with Gilead’s larger project, the Compass Initiative, which combats the South’s HIV/AIDS epidemic. Gilead has dedicated more than $100 million for the 10-year initiative, partnering with community-based HIV/AIDS organizations in the South to reduce the epidemic.

The campaign targets the “Bible Belt” (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas).

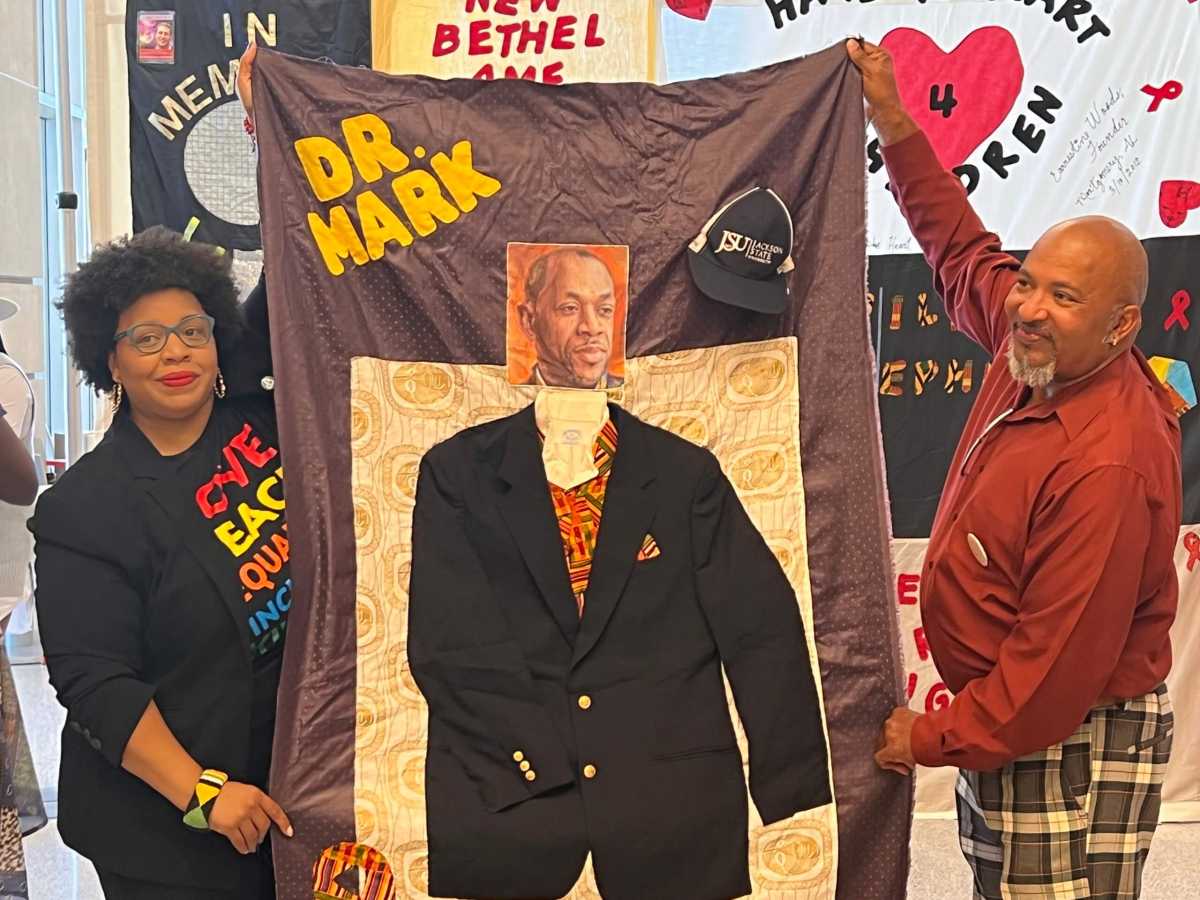

The Quilt’s first Southern five-day event was hosted in Mississippi from September 28 to October 4. Up to an estimated 5,000 people viewed more than 500 panels of the Quilt and participated in a variety of events across Jackson and the Delta. The Southern AIDS Coalition has been working in conjunction with the National AIDS Memorial to coordinate the work in the south.

One of the panels displayed was created by the late civil rights icon Rosa Parks, a supporter of the Quilt, that she made and signed for her friend, Deborah Haynes.

“Rosa Parks was a seamstress by trade. She had lost family members and friends to AIDS,” said Herglotz. HIV/AIDS and the AIDS Quilt was “a justice issue” for her.

“She felt strongly about it, and she connected it to what was happening during the darkest days of the AIDS pandemic injustice,” he continued.

The message

Herglotz said that the message of the Quilt in the South is the same message it’s carried through the decades: bringing communities together, storytelling, education, and support.

In many cases, the Quilt has been a method to get information to youths in public schools where HIV/AIDS health educators, some who are Quilt facilitators, don’t have access, especially in the deep South, Harris said.

“We encourage health educators to use the Quilt to piggyback on to use it as a tool to do some of the work that they’re trying to do,” she said.

Harris said in some communities the stereotype that HIV/AIDS is a “gay white man’s disease” persists to this day.

Harris recalled when she first started at the National AIDS Memorial, a young Black man working to educate his college community about HIV/AIDS requested a set of panels that weren’t of “old white guys.”

She looked up the event, a Multicultural Health Fair at Eastern Carolina University, and the panels that were sent were of all white men.

“This young Black man knew that it was not serving the purpose that he needed or his fellow students on campus,” Harris said. “We need to get more quilts made by and for people of color so that we can make a connection.”

BIPOC voices

Herglotz said that the National AIDS Memorial with Gilead wants to make sure Black and Brown people’s stories and the communities impacted by the epidemic are told and celebrated.

In 2021, the HIV/AIDS epidemic marked its 40th anniversary. In the United States, there are more than 700,000 lives lost to HIV/AIDS, Herglotz said. There are only 110,000 names in the panels of the Quilt.

“When the Quilt first started in the 80s, it started because people’s friends were just disappearing. They’re here one day, they’re gone the next,” said Harris. “Some of that is happening in Black and brown communities today. It’s not really being talked about.”

“The Quilt has a lot of stories to continue to tell,” Herglotz added.

The National AIDS Memorial has been partnering with Historically Black Universities and Colleges to help get the message out.

Some young people might be inspired to try to find a cure someday, she said, recalling meeting medical professionals and scientists over the years who saw the Quilt when they were students and “they decided to dedicate their lives to finding a cure.”

“The same can happen for these current young people when they see people who look like them there,” Harris said. “They can really say, ‘What can I do to save myself, save their community?’”

The impact of the Quilt is raising awareness, funding, and providing resources to hard-hit communities by HIV/AIDS in the South. The Quilt helped raise $100,000 to create a fund to support local Mississippi HIV/AIDS organizations impacted by the water crisis, Herglotz said. In Alabama, the organization is giving grants to some of the local HIV/AIDS organizations.