Ali Forney Center’s Carl Siciliano, VOCAL-NY’s Jawanza Williams, New Alternatives’ Kate Barnhart, and the Coalition for Homeless Youth’s Jamie Powlovich at an April 26 City Hall press conference. | DONNA ACETO

Under legislation signed this month by Governor Andrew Cuomo, the maximum age at which homeless young people can seek emergency housing separate from the adult shelter system has been raised from 20 to 24. Advocates for homeless youth are now turning their attention to the de Blasio administration and the city’s Department of Youth and Community Development (DYCD) to fund shelter beds for this population.

As with homeless young people 16 to 20, those who work with youth have long identified adult shelters as dangerous places for those in their early 20s. In a written statement, Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams — who played a pivotal role in pushing the Albany legislation in partnership with its sponsors, Assemblymember Helene Weinstein, a Brooklyn Democrat, and Senator Diane Savino, a Staten Island member of the Independent Democratic Conference — pointed out that homeless people under 25 often have “fears of bullying, harassment, sexual assault, and violence” in adult shelters and so instead choose to live on the street, something that forces many of them to engage in survival sex.

According to experts on LGBT youth homelessness, including Carl Siciliano, executive director of the Ali Forney Center, and Kate Barnhart, who heads up New Alternatives for Homeless LGBT Youth, queer young people are particularly at risk in the adult shelters. In a memo to the seven lesbian and gay members of the City Council, Siciliano said there are “hundreds of frightened and imperiled LGBT homeless youths in our care who currently have no access to safe shelter.”

With state runaway, homeless youth law age limit raised, attention turns to city

Studies of the homeless youth population in New York and nationwide suggest that as many as 40 percent of young people living on the streets identify as LGBTQ.

In an interview with Gay City News, Siciliano said that housing for 21 to 24-year-olds “is the one great structural hurdle remaining” in the city’s effort to address the problem of homeless youth.

The push to expand specific housing for homeless youth up to the age of 24 dates back to at least 2010, when a commission appointed by then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg identified the 21-24 age range as a group at risk as much as younger people. In response to that commission’s report, DYCD broadened access to youth drop-in centers and to its street outreach efforts to those as old as 24. The department has consistently taken the position, however, that its shelter program be limited to youth 16 to 20.

Among the reasons DYCD has cited was the State Runaway and Homeless Youth Act, which until now applied only to those under 21. According to Siciliano, attorneys who have examined the legal issues told him that the state law imposed no barrier to the city expanding its housing program, but he met with resistance from the city on that point. In any event, the new legislation removes that barrier.

The debate over housing 21 to 24-year-olds emerged during a period when advocates were fighting tooth and nail to provide beds for homeless youth under 21, and to some extent there has always been tension between serving the youngest homeless people and turning attention to the older segment of youth. During the Bloomberg years, there were repeated budget battles between the mayor, who would zero out funding for homeless youth beds in every budget cycle, and the City Council, led by then-Youth Services Committee chair Lew Fidler of Brooklyn and Speaker Christine Quinn, who worked to restore what funding there was. By the end of Bloomberg’s third term, only about 250 emergency beds for homeless youth existed in the city — which meant long waiting lists for vulnerable young people with no alternatives.

During his 2013 campaign, Mayor Bill de Blasio pledged to grow that supply by 100 beds each year. The stock now stands at roughly 450 beds, with another 100 in the pipeline — an expansion the city has shouldered without help from Albany. According to both Siciliano and Barnhart, the 200 new beds have made a significant contribution to eliminating the waiting list problem. Barnhart, whose organization works to connect homeless LGBTQ youth with appropriate housing, said she can usually arrange placement for a client under 21 within a few days. For those 21 to 24, however, it can take up to six months to find safe emergency shelter outside the adult system.

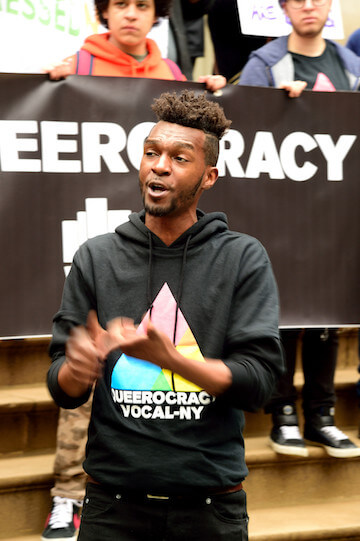

VOCAL-NY’s Jawanza Williams predicted “the city will ultimately not have a choice” but to provide more housing for the 21 to 24-year-old population. | DONNA ACETO

To date, the only alternatives for this age group have been fewer than two dozen beds provided by Ali Forney, Trinity Place, and Sylvia Place — all of them privately funded. One step the city has recently taken is the opening of Marsha’s House in the Bronx, which is geared toward providing housing for LGBTQ homeless people 21 to 30. That effort, however, is run out of the Department of Homeless Services, not DYCD, and a young person first has to spend time in an adult shelter before gaining entry to the Bronx facility.

On April 26, advocates gathered on the steps of City Hall to press the de Blasio administration to step up on providing DYCD beds to the 21 to 24-year-old population. Siciliano and Barnhart were joined by representatives from VOCAL-NY and the Coalition for Homeless Youth, as well as Councilmember Stephen Levin, who heads the General Welfare Committee.

By all accounts, DYCD’s reluctance on the issue has been a concern about not undercutting its efforts with 16 to 20-year-olds, given the funding it has available.

“They have been concerned about resources,” said Barnhart, “that if they stretched to meet the needs of older youth, they would do so at the expense of the younger group. But rather than setting the younger youth piece of the pie against that of older youth, we need to get more pie.”

Jamie Powlovich, the executive director of the Coalition for Homeless Youth, summarizing her sense of where DYCD is on the question of providing beds for the older age group, said, “They don’t oppose it completely but they want to make sure it is different and separate from the resources for 16 to 20-year-olds.” Noting that 100 new youth beds should come on line soon, she added, “DYCD is not open to opening those beds to the older youth.”

As a result, Powlovich said, advocates are seeking new resources — specifically $4.8 million, which she said would provide 50 beds for older youth, as well fund the hiring of housing specialists at all DYCD facilities to work helping young people find permanent housing solutions and the establishment of two new 24-hour drop-in centers for homeless young people up to age 24. Currently, the only such facility in the city is run by Ali Forney in Harlem.

Jawanza Williams, a youth organizer at VOCAL-NY, said, “I think the city will ultimately not have a choice” but to provide more housing for the 21 to 24-year-old population. “The biggest barrier,” he said, “for DYCD before was state law that would not allow this. Now they have no excuse, and it’s our job to hold them accountable.” DYCD, Williams added, “knows the need.” He also noted that given the city’s commitment to the Plan to End AIDS, the mayor and other policymakers should see the importance of providing safe housing for vulnerable young people who, without stability, run greater risk of either becoming HIV-infected or, if positive, being unable to keep their viral load under control.

In advocating for DYCD stepping up on older youth, Siciliano is putting particular emphasis on the Council’s lesbian and gay members. In his recent memo to the group, he wrote, “I hope that you will join us in our urgent call for the mayor and DYCD to raise the RHY age to 24. It is inexcusable that our progressive city, with the nation’s largest homeless LGBT youth population, is lagging behind the state and federal efforts to end youth homelessness, both of which now define Runaway and Homeless Youth as being 16-24 years old… it is troubling that our city, with its relatively robust LGBT political leadership, is not in the forefront of this effort to protect its most vulnerable young people.”

In a written statement, out gay Chelsea Councilmember Corey Johnson said, “When it comes to runaway and homeless youth — many of whom are LGBTQ — we have to acknowledge that the need for these services doesn’t just disappear when they turn 21. We must bring our age requirements in line with federal standards and give DYCD the resources it needs to address this pressing issue.”

The Bronx’s out gay Councilmember Ritchie Torres, a leader on the effort to launch Marsha’s House, which is in his district, has also voiced support for increased housing opportunities for homeless youth over 20.

As of press time, neither DYCD nor the mayor’s office responded to a request for comment.