Scott Robbe, an early and important member of ACT UP and Queer Nation and a founder of other activist groups, died on November 21 in hospice care in his sister’s home in Wisconsin after a year-long battle with myelodysplastic anemia, a form of blood cancer. He was 66.

“He was always one to take charge, kind of looking out after his sister, Angie,” said John Robbe, Scott’s brother and one of five children in the Robbe family. “Looked after most of us. He always made sure everyone was okay.”

Scott, who was the oldest of the five children, was born in 1955 in Iowa and raised in Wisconsin with his three brothers and one sister. His father, James Robbe, was a construction supervisor and his mother, Helen Robbe, was a homemaker. Scott credited his father with raising him in an “activist household,” according to his 2013 interview with the ACT UP Oral History Project.

“I think there was a strong sense of community that was given to me by my father, who was always very active in the community on ecological issues, community issues that affected the broader community,” Scott said.

He was also exposed to more radical politics as a teenager. A babysitter gave him a copy of “Living My Life,” the autobiography of anarchist Emma Goldman, when he was 13. That babysitter was the girlfriend of Leo Burt, who was indicted but never apprehended in the 1970 bombing of the Army Math Research Center on the University of Wisconsin campus. The bombing protested the American war in Vietnam. Scott said in his interview that his parents knew about the babysitter’s politics.

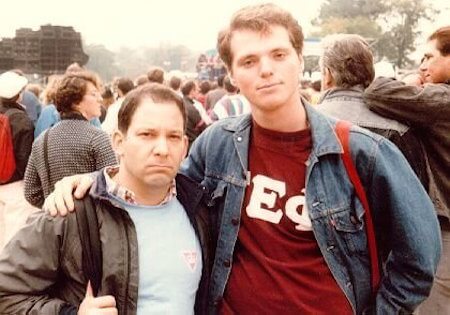

Robbe is credited with joining some of ACT UP’s more daring protests, such as briefly halting the opening of the New York Stock Exchange in 1988. He joined ACT UP, the HIV activist group, after seeing an ACT UP protest during the 1987 Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. He modernized ACT UP’s protests by using cellphones and walkie-talkies. As a member of ACT UP’s media committee, he promoted upcoming protests with displays on unused billboards around New York City.

“I came to ACT UP because I’d always been a fervent believer that if you want to create change, you have to participate,” he said in his interview. “Democracy doesn’t work unless you participate. You can’t foster change unless you participate.”

Scott moved to New York City after graduating from the University of Wisconsin in 1978 with a degree in theater, according to a biography that was compiled by Jay Blotcher, a publicist and former ACT UP member. He produced Off-Broadway shows, including workshopping “Fugue in the Nursery,” which was the middle segment of Harvey Fierstein’s “Torch Song Trilogy,” at La MaMa, the experimental theater collective in the East Village, and producing “False Promises” by the San Francisco Mime Troupe at the Entermedia Theatre. Scott was part of a collective that was renovating the Orpheum Theatre in the East Village. He produced the Harvey Fierstein play “Safe Sex” on Broadway.

In 1990, Robbe moved to Los Angeles to produce commercials for Japanese television and he began a career in producing films and television shows. While he eventually enjoyed success in film and television production, he was initially hampered by his activism. In 1991, he was among a group of activists who founded Out in Film, an organization that protested how LGBTQ people were represented in films and on television and the discrimination they faced in working in that industry. Out in Film, ACT UP, Queer Nation, and other groups protested during the 1992 Oscars.

“That really made me persona non grata in Hollywood at the time,” Scott said during his interview with author Sarah Schulman for the oral history project.

His producing career in television and film continued through 2013, according to credits listed on imdb.com, but he had returned to Wisconsin by 2005 where he launched a volunteer effort to bring major Hollywood productions to the state. In 2007, that organization, Film Wisconsin, was made official and Scott was appointed executive director. The Blotcher biography credits him with bringing “28 TV and film projects to the state.”

Throughout his career, Scott maintained relationships with friends he made in college and later in his life. Scott had retired in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico when the cancer struck. He went to Boston to receive a stem cell transplant that was ultimately unsuccessful at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Two friends Scott knew from his childhood or his time at the University of Wisconsin — Ben Fraundorf and Mike Mack — traveled to Boston to care for Scott.

“I would always think of him as being very much an activist, very much caring about people, making sure that everybody was treated fairly,” Fraundorf told Gay City News. “My wife was equally as much a friend of Scott as I was…My thought was if this happened to me, I’m sure Scott would have been there as well.”

Former ACT UP colleagues echoed Fraundorf’s view of Scott.

“Scott was not only a man with big heart, but he had a remarkable sense of humor,” John Voelcker, a former ACT UP member, told Gay City News. “I might not talk to him for six months or 18 months, but when we picked up the conversation, it was as if no time had elapsed and that to me has always been the mark of a good friend.”

In an email, Blotcher wrote that Scott “was an old-school leftie” and his work in “ACT UP and Queer Nation were a logical continuation of that spirit. Scott had the historical perspective that many of us activist newcomers lacked, and perhaps that accounted for his patience and persistence. He knew how to play the long game when it came to social justice.”

Scott is survived by his mother and his four siblings and their spouses, an uncle, and several nieces and nephews. Donations in Scott’s memory may be made to Broadway Cares/Equity Fights.