Robert Mitchell, Sturgis Wagner yield impressive results with risky musical about Van Gogh’s life

In crafting a musical based on the life of Vincent Van Gogh, Robert Mitchell has set a tremendously high bar for himself—to create art from the process of art. The storytelling resources available to Mitchell are limited––what is known about Van Gogh comes mostly from 650 or so letters he wrote to his brother Theo. That limitation tends to give a very narrow perspective and self-involved focus to the narrative.

Yet, rather than move into abstraction and a fabricated story as Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine did with “Sunday in the Park with George.” Mitchell instead has written a “docu-musical,” which chronicles Van Gogh’s life. Though dramatically hampered by its episodic structure, “Vincent,” on stage this month at the Wings Theatre, is clearly the work of an intelligent and sophisticated playwright and composer.

What the show hints at but never fully delivers is a much larger drama about the struggle for connection, the power of expression, and the drive by the spirit to find freedom in a world rife with harsh realities. While we watch the sad descent into alienation and madness of a great artist unrecognized in his time, we are engaged but not touched as deeply as we might be.

But these are quibbles about an ambitious show that is successful in many ways.

“Vincent” is best described as a chamber musical in which ten actors portray the myriad characters who inhabited Van Gogh’s life. The set is nothing more than a black box and ten stools, and yet director Sturgis Warner manages to evoke a rich world through the use of his company and creative staging. This is certainly a case where less is more. In the second act, there is a scene in which Gauguin and Van Gogh have been painting together at Van Gogh’s famous yellow house in Arles. As the tension between the two men grows, Warner moves his company in to surround them, adding to the sense of confinement. Consistently throughout the show, he finds the exact juxtaposition of actors and attitudes to supply the emotional content in what are otherwise episodic scenes. The director’s success results in a visually stunning production that makes a virtue out of simplicity. Those who know Van Gogh’s work will love how his composition of “The Potato Eaters” is reproduced using only stools and gestures.

The show is virtually sung through, and the score is both daring and intriguing. It is actually refreshing to hear someone who is willing to push the harmonic envelope a bit, and while it’s easy to draw parallels to the work of Sondheim or Michael John La Chiusa, Mitchell has a voice of his own, finding a lyricism in harmonies both fresh and rooted in tradition. Mitchell tailors the music to the dramatic integrity of each piece, ranging from dissonant harmonics that scream of the torment Van Gogh feels to a slyly ironic “traditional” verse/chorus number about what will sell in the commercial art market of 1886.

A score of this nature requires singers of more than exceptional ability, and Mitchell and Warner are blessed in their cast. Of the ten people onstage, every one more than meets the demands of the score and, even more, radiates star quality.

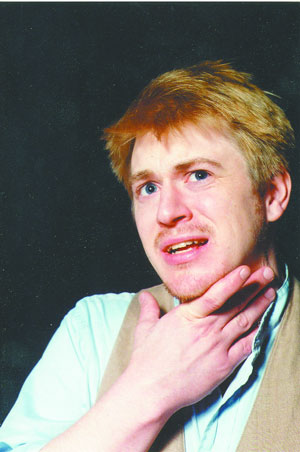

In the title role, Paul Woodson is remarkable. His lyric baritone is clear and effortless, and his acting is superb, which make his performance consistently riveting and quite often thrilling. The role would test the range of any baritone, yet Woodson moves fluidly through it, at times finding the placement and resonance that works magic, fully appropriate to the size and intimacy of the character.

Among the rest of the cast, Greg Horton as Lautrec, Dave Tillistrand as Gaugin, Cristin J. Hubbard as the prostitute Sien with whom Van Gogh lives for a time, Bess Morrison as a tavern girl and purveyor of absinthe, and Erik Schark as Theo all have moments of real brilliance. The balance of the company—Stanley Bahorek, Ronald L. Brown, Elisabeth Van Duyne, and Catherine Walker are also superb.

In “Sunday,” Sondheim has Georges Seurat say, “Art isn’t easy.” Anyone who creates musicals knows that. Yet I, for one, will take an imperfect but risk-taking show like “Vincent” over the glossy facility of something like the current “Fiddler” revival any day.