Evoking colorful dreams, Suzanne Wright creates a Grimms-like landscape of spooky travails

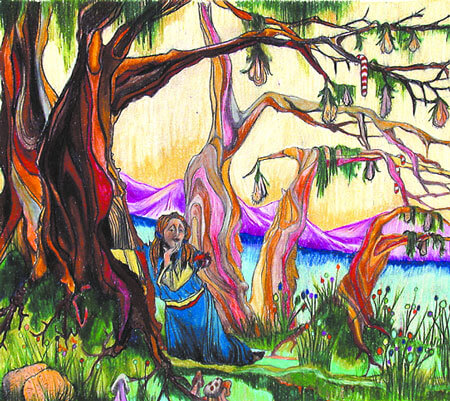

“The Testicle Tree Series” is the strangely clinical name for a suite of eight drawings that transport us to a magical, funny world of girlhood yearning. Welcome to the fairy forest of Suzanne Wright. Gnarly, labial trees laden with candy canes and delicate sacs arch languidly over meadows carpeted with marshmallows, mushrooms, and wildflowers. “Maidens’ Home,” a rainbow-colored cottage, is nestled into a psychedelic burst of vegetation. Tender heroines loiter wistfully, copping campy poses worthy of Lillian Gish in “Broken Blossoms.”

Wright’s small, carefully rendered drawings use the formal language of storybooks to tell a narrative in which girls are the sole protagonists. Missing grown-ups appear in the form of cartoons: gaping vaginal shapes, teeny-weeny bulbous mushrooms, gangly testicles, and all manner of sexualized flora teasingly play up essentialist notions of landscape-as-body. The physical aspects of the drawings themselves—lap-sized, vigorously outlined and filled-in with colored pencil—conjure up the image of a prepubescent girl in her bedroom, laboring over a Technicolor fantasy of adulthood.

At a time when most children are more familiar with the Power Puff Girls than the Brothers Grimm, Wright’s use of the storybook illustration becomes a quaint gesture towards an imaginary childhood and ties her further to literary works, such as Angela Carter’s “The Bloody Chamber,” a feminist retelling of fairytales and the social narrative of female development.

In “Forest of Plenty,” Wright complicates her project with a nod to American transcendentalist landscapes and the dreamy, fecund paintings of the anointed grandmother of feminist art, Georgia O’Keefe. O’Keefe was inspired to create her seminal painting, “The Lawrence Tree,” by lying beneath a massive New Mexican tree, looking at the glittery night sky through a verdant crown of leaves.

Wright’s towering tree is devoid of leaves, instead presenting a crop of droopy, hairy scrota, each springing from a thatch of Spanish moss. Wright slyly disrupts implications of a “naturalized” sexual power embedded in O’Keefe’s biomorphic abstractions (such as “Old Maple, Lake George,” 1926) by showing us a dried-up old tree sprouting its sad, flaccid sacs.

If you can imagine wanting one, they’re ripe for the picking.