Mitchell Algus looks at the woman-positive sexuality pioneered in the 60s

The Mitchell Algus Gallery continues to set the standard for recuperative exhibition programming with this vibrant group show of feminist work from the 60s, 70s, and the present. It will be especially useful to the young, those with trend-disabled vision, or memory loss. Algus has mounted the exhibition in response to recent shows featuring male sex and sexuality staking out the wry, yet playful assertion that the girls were there first.

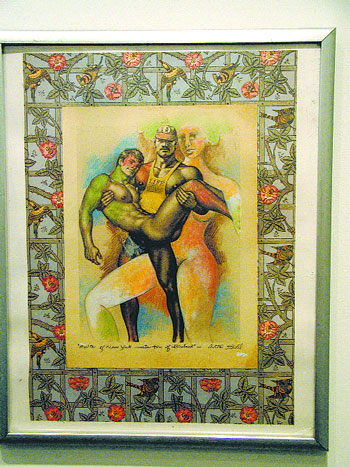

Sex is indeed the subject in a fabulous in-your-face, the personal-is-political way. This small gallery is packed with 17 works that range from a haunting expressionist painting of female bleeding by Juanita McNeely, to warm and wild multimedia paintings by Anita Steckel.

Steckel, in particular, recalls an approach to woman-positive sex in the city that renders contemporary versions as the vacant marketing ploys that they are. In “Inner Landscape On New York #3” from 1977, she paints massive “Eves” looming and lounging in and around a photo-silk image of the Manhattan skyline. Stars of David dance in the sky, and gefilte fish swim in the Hudson. The Empire State Building is drawn into a big penis, of course. It’s sweet, a little rude, and oddly un-hip by today’s standards, making it an amazing example of the complex roots of identity art.

Judith Bernstein and Eunice Golden are also real “finds” for those of us not yet acquainted with their work. Set among the better known women in the show, like the recently “re-emerged” Betty Tompkins, Joan Semmel, Hannah Wilke, and second waver Kathe Burkhart, they fill out the field of vision. Bernstein holds down cooler, perhaps more conceptual territory with her “One Diagonal Hardware” from 1971. In this four-panel work on paper she breezily renders screws floating and flanking on an open ground. Small diagrammatic gestures accent the ribbed shaft of the hardware, suggesting the twist of screwing action. Similar charcoal gestures indicate the slot at the top of each head, resulting in the image of tiny phallic emissions. Bernstein, like the others, seems to know something about getting screwed.

Tomkins puts it right out there in her “Fuck Painting #5” from 1972. There’s enough veined shaft there for everyone to love, or not. Her photo-real fidelity and compositional candor recall the truth telling of consciousness-raising groups and the particular dilemma of straight feminists illuminated during the first wave.

Burkhart carries the torch, but leaves the boys behind with two pithy works from 2004. Her “Through the Wringer” is the perfect rejoinder to any doubt about the continuation of this brand of feminism. In it, Burkhart redraws the cover of Judy Chicago’s “Though the Flower” replacing Chicago’s gynocentric mandala with a picture of a pissed-off woman with a massive migraine. She’s just reminding us, it’s not over until the fat lady screams!