Thrice back from death’s door, Larry Kramer to address gay culture at Cooper Union

On Sunday evening, November 7, five nights after this just decided, bitterly fought presidential election, a Jeremiah named Larry Kramer takes to the lectern of the Great Hall of Cooper Union.

From that historic spot, where on February 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln delivered an address that stirred the nation and put him on the road to the White House, the man who woke up the nation to AIDS in the 1980s will pass judgment on the results of the 2004 presidential election.

Of course, Larry Kramer has long been firmly convinced that Abraham Lincoln was gay all his life, but that’s (perhaps) another matter.

What precisely he will say at Cooper Union, Kramer won’t say, but in any event it will not be mild. Two weeks earlier—Sunday, October 24—playwright, screenwriter, novelist, moralist, lifelong activist Kramer was honored for that life, those works, in an evening at the 92nd Street Y hosted by playwright Tony Kushner and chaired by author Calvin Trillin.

“George W. Bush?” said Kramer two weeks before the 92nd Street Y event. “He’s hateful. What more is there to say? If he gets re-elected, it’s just going to be awful. We’ll know after the election just how much trouble we’re in.”

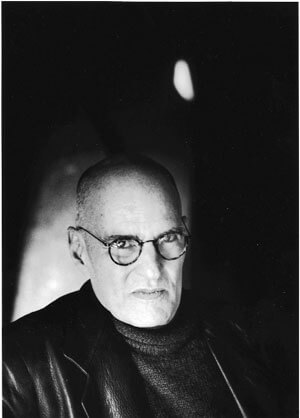

He was saying this in the living room of his lower Fifth Avenue apartment. Unshaven, scraggly looking, weary, but open to all questions and more than affable, the terrible-tempered agitator who has survived a liver transplant and much else was keeping up his strength by munching on salad from a plastic take-out container between an interviewer’s Q’s and Kramer’s A’s.

As good a place as any to start would seem to be a line from the play by Larry Kramer that two decades ago broke all performance records at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater and has since had more than 600 productions all over the world.

JERRY TALLMER; In “The Normal Heart,” you have a character saying, as the AIDS terror digs in, “Maybe if they’d let us get married to begin with none of this would have happened at all.” That certainly echoes retrospectively against George Bush’s advocacy of a constitutional amendment against gay marriage, doesn’t it?

LARRY KRAMER: Yes. Well, that was written in ‘82 or ‘83, and put on at the Public in ‘85. There wasn’t any division then between civil union and marriage like there is now. But basically, yes, I think if there’d been legal recognition it would have helped … [With irony] A lot of things would have helped. But marriage and all that is a drop in the bucket as to what caused AIDS and what didn’t cause AIDS.

JT: I don’t suppose you’ll tell me what you’re going to say at Cooper Union.

LK: No, but I am going to talk about where we are now as a people. The title is “The Tragedy of Today’s Gays.” The original title was “Who Are We, Where Are We Going?” but I settled for “Tragedy” because I think what’s happened to us is tragic.

JT: The tragedy of today’s gays in Greenwich Village and so forth? Or in Africa, China, all over the world?

LK [morosely]: Take your choice… but particularly in America.

JT: Is the situation not somewhat better than it once was?

LK: I guess you never get anywhere if that’s what you think.

JT: You don’t convey it in your tone of voice as we sit here, but you’re still very angry.

LK: I don’t think I’m angry, but that I’m concerned, intelligent and see things other people don’t. Or people see things but don’t talk about them.

JT: You’ll be speaking at Cooper Union five days after the election. Any thoughts ahead of time

LK: Obviously, if Kerry gets elected there’ll be a modicum of hope on the table. But either way, I don’t think it makes all that much difference.

JT: Kerry makes me nervous in his hemming and hawing on certain things––for instance, gay marriage.

LK: I have a feeling on that issue that if he’s elected he’ll be able to say and do things he can’t say now. That’s what I’m hoping. Whereas you know Bush is not going to… [lets it trail off].

JT: Are you as angry at Bush as you were at Reagan? Who, as you keep reminding us, never mentioned AIDS his first seven years in the White House.

LK: Yes, [Bush] is terrible. More than anyone we ever had. He’s a different person, now that he’s found God and all that.

JT: I don’t know if he’s found God or just likes to say so.

LK: I agree with you. But this is a never-ending process, all these enemies. Including Clinton. You can’t separate one from the other. Still, you know, the anger that one had from 1980 to ‘86, say, was different from the anger one has now. I don’t know if I am as angry as I was. I’m 69 years old, and the anger has been so absorbed into my body that it’s become something else––despair. Tony Kushner, in an address at Yale a couple of weeks ago, said that despair is immoral. [With a smile and a flash of the old wit] But he’s younger.

JT: The character Ned in “The Normal Heart,” the sardonic guy who’s always raging at everybody, he’s obviously you.

LK [with a different smile]: Stephen Dedalus and James Joyce?

JT: True or false?

LK: It’s there.

JT: At the end of Act I this Ned is talking to his boyfriend and he says: “Felix, weakness terrifies me. It scares the shit out of me. My father was weak and I’m afraid I’ll be like him. His life didn’t stand for anything, and then it was over. So I fight. Constantly. And if I can do it, I can’t understand why everybody else doesn’t do it, too. Okay?” May one ask about your father

LK [with a shrug]: My father was a lawyer for the government in Washington, D.C., where I grew up. He died many years ago, at 70. My mother lived to be 98… He knew I was gay. Or probably suspected it.

JT: When did you realize you were gay?

LK: Oh, who knew, in those days. Self-knowledge and discussion were not available. Homosexuality was not written about in the papers. I knew I was different from the age of four.

JT: I enjoy that you took Ned’s name from the gentle brother in Philip Barry’s “Holiday.” All the more so when your character says: “So I fight––constantly.” [Pause.] It looks like I’m trying to explain you to you.

LK: Don’t. [Pause.] I guess my father was depressed. But he was weak. I didn’t fight for anything particularly until HIV came along.

You know, I was quite successful in my career. Wrote movies [notably the Oscar-nominated adaptation of D.H. Lawrence’s “Women in Love”], a novel [“Faggots”], a couple of plays. One of them was called “Sissies’ Scrapbook,” for Playwrights’ Horizons. When it was then done at the Theater de Lys [now the Lucille Lortel], the title was changed to “Four Friends.” The producer wouldn’t let it be called “Sissies’ Scrapbook.”

JT: Was the producer gay?

LK: Sure. He’s dead now. “Faggots,” you know, didn’t impress many people at first, but it’s still, now, very successful. Never been out of print. A new edition is just out with a preface by Reynolds Price. And there’s never a week “The Normal Heart” is not being done somewhere in the world.

JT: If all those things weren’t forms of fighting…

LK: I guess they were. But I just wasn’t a political activist per se.

JT: That subsequently famous page 20 New York Times article in July 1981 that told the world––whispered to the world––about a strange cancer that was killing young homosexual males––did you read that story at the time?

LK: That’s what got me started.

JT: Had no awareness of something wrong before that?

LK: In retrospect, one realized one had lost friends to AIDS, but one didn’t put two and two together at the time. One of my good friends, Dr. Larry Mass, had a health column in The Native, and he alerted me to what was happening.

JT: Your Ned says, “Talking is not my problem. Shutting up is my problem.” Does that still go? You seem so quiet, here and now. Unalarming.

LK: Well, I’m 69 years old now and was much younger then. I’ve been very close to death three times. I don’t know what you expect to see. A rabble-rouser I was. But actually I’ve always been sort of soft-spoken, outside of a political forum.

JT: Tell me about the three near-death experiences.

LK: Oh God… The first one, in 19-something––whatever year I was diagnosed with HIV, right after my play “Just Say No”––and I had to go in a hospital. They opened me up and found I had this liver disease. If they hadn’t opened me up, I think I would have gone down.

The second two times were all related to the liver. Two years ago I had a liver transplant. It took a long time to get the liver.

JT: Did you ever find out whose liver it had been?

LK: You can find out if you want to. My shrink advised against it. [Two beats.] It was a very good liver.

JT: The liver thing has nothing to do with HIV, or does it?

LK: Of course it had a lot to do with it. Makes the liver bad.

JT: About your upcoming Cooper Union talk…

LK: You know, Cooper Union is home base for a lot of us. Because the Great Hall is where ACT-UP used to meet.

JT: Does ACT-UP still exist and do things?

LK: Yes. Did things at the Republican Convention, when all those people got naked.

JT: Not to change the subject, but do you live with anyone nowadays?

LK: I do. Want to see his picture? He’s gorgeous. [Gets up, crosses the room, returns with a couple of snapshots.] He’s David Webster. Like the dictionary. An architect.

JT: How long have you been together?

LK: This time? Ten years. After a 17-year gap since the first time. It didn’t work the first time.

JT: How’d you meet again?

LK: I wanted to build a house in Litchfield County, Connecticut. [The house got built, and it’s where Kramer spends half his life, the other half being in this apartment.]

JT: Your character Ned rages against the Jews––the American Jews––who kept their mouths closed during Hitler. As analogy to the early silences of gays on AIDS. May I raise the Jewish question? Was that a problem congruent with being gay?

LK: I never had any trouble being Jewish. I never encountered any anti-Semitism. None. [Two beats.] Oh, you mean was I fucked up? Oh, boy. Not because I was a Jew. Because I was Larry. It had to do with my parents, and being unhappy, and like that. I went to lots of shrinks. They’re all listed in the play. David [Webster] and I go just for couple’s therapy. When we have a fight or something.

JT: Are you looking forward to the thing at 92nd Street?

LK: Yes. Calvin Trillin is one of my best friends. We went to Yale together. And Tony Kushner is a great writer and a great person and a great friend. They’re going to put on scenes from my plays, and Tony won’t tell me what scenes or what actors. “Angels in America” is just cosmically great. Shakespeareanly great. Tony’s Talmudishly smart. I was born June 25, 1935 [and Kushner on July 16, 1956], but I always think of him as older. I look up to him as older.

JT: If there is one main villain in your play, “The Normal Heart,” and in your whole gay activism, it is Edward I. Koch, sometime Mayor of New York City, who has never acknowledged his sexual orientation, if any.

LK: Yes. I consider him as the one person most responsible for the AIDS plague.

JT: In this city.

LK: In this city and elsewhere.

JT: And now, of all things, he lives here in this very building.

LK [dryly]: We don’t talk. We pass each other in the halls and don’t talk ..

Well, thanks, Mr. Kramer. And there must be a play in that, somewhere. The odd couple of lower Fifth Avenue. A smasheroo.

The interviewee had finished the salad in the plastic container, and saw his inerviewer to the door. It had been a useful visit. I wouldn’t mind going back sometime.Larry Kramer appears at Cooper Union’s Great Hall on Sunday, November 7 from 7 to 9 p.m. in an event hosted by John Cameron Mitchell and produced by the HIV Forum.