Theater, film and publishing professionals discuss the role of collaboration in their art

A group of playwrights and artists gathered at the Spike Gallery on West 20th Street, facing the Chelsea Piers, on the evening of November 15 for “The Art of Collaboration,” a panel discussion on the challenges and rewards of working as a team.

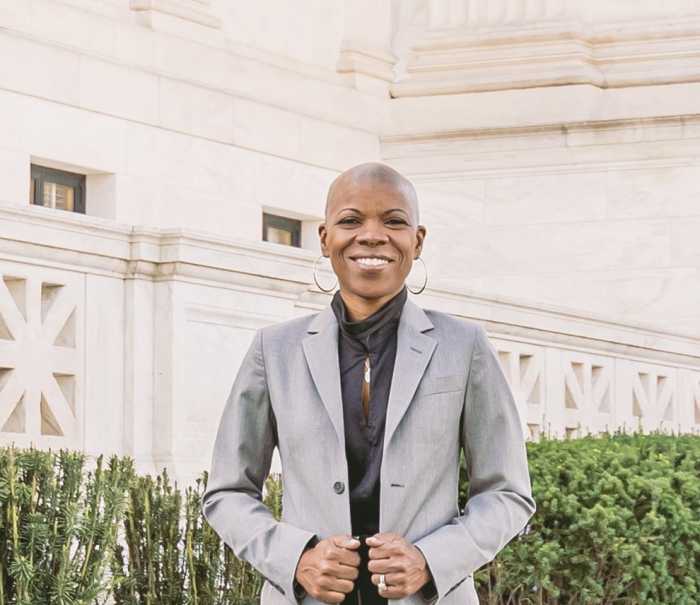

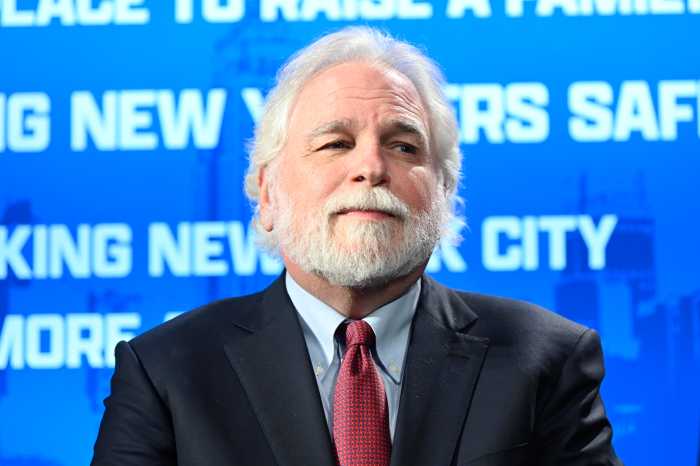

The panel was part of Richard Nahem’s Art of Creation series, bringing notable New Yorkers together to discuss the arts. The panel included writing team Christopher Ashley and Paul Rudnick, married designers Massimo and Lella Vignelli, playwright Thomas Meehan, director David Warren, filmmaker Shirin Neshat and Radar editor Maer Roshan. Writer Jesse McKinley served as moderator.

“Part of creating has a lot to do with collaboration, especially with the people up there,” said Nahem. “By nature what they do is collaborative. A playwright is in solitary when writing a play, but in order to have that work realized and produced, they are forced into collaboration.”

“Working in the theater, you have to,” said Rudnick, starting the discussion. “When you are facing an audience, you need someone else in the room to say, ‘Good, right direction.’ It’s oxygen. I am stunned by people who direct their own work… it must be lonely. Who do they blame?”

“I don’t know if we married to work together or work together because we’re married,” said the garrulous Vignelli. “After a while, your work becomes the byproduct of a symbiotic relationship, and that is the great experience of being a couple.”

His wife Lella echoed, “If we were not working together, we would not be married still. Mossimo is a nut for design, and if I didn’t [share his interests] it would be impossible.”

Most panelists agreed there were challenges to collaboration.

Warren, who directed the breakout hit “Matt & Ben,” a spoof on the stardom and friendship of Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, said the hardest thing about working with emerging artists was making them understand he respected their views.

“Why become a director if you want to tell people what to do? My best ideas come out of other people’s ideas,” said Warren.

Meehan spoke of his work with the legendary Mel Brooks, saying, “My main job in collaborating with Mel is to say, ‘That idea really stinks. You’re Mel Brooks!’ Mel knows where the laughs are… but also oddly, he doesn’t.”

Does going against the grain lead to fights, asked McKinley?

Ashley and Rudnick, who have worked as a team for nine years, said the key was trust, which came over time.

Warren said the only real problem came when collaborators squared off into teams, saying, “Then you’re really dead.”

“Good collaborators don’t fight, they disagree, and bring out the best in each other,” said Meehan, citing Rodgers and Hammerstein.

Roshan added, “I fight fiercely with all the best writers I have, because they believe so passionately in what they are doing… You get these 4 a.m. calls, ‘Does Daddy still hate me?’”

Neshat seemed somewhat soured on the idea of collaboration after being unduly influenced in the past, saying, “Now I surround myself with overly talented people, and make sure what I achieve is my initial vision. I am becoming less democratic and idealistic about my vision.”

Mossimo Vignelli said for him and his wife, the client is the collaborator, who comes with his own problem and vision for a solution. Rudnick said he relied on certain actors to bring clarity. Lella Vignelli said she liked to go to the craftsmen, whom she has found to be both knowledgeable about the process and passionate about the work. Warren noted that the most important part was weeding through “floating opinions” to get feedback from two or three trusted friends. Meehan said he has relied on the opinions of director Mike Nichols and other older statesmen of the theater, and Roshan talking about turning to Tina Brown, his boss at the now defunct Talk magazine.

All agreed that at the end, the audience was the biggest collaborator, deciding whether something stays or goes.

“Especially in comedy, the joy and peril is the first preview,” said Rudnick. “There is no press, no buzz—the audience is virgin. If they laugh, it is such a deep and lasting satisfaction.”

“And the audience is always right,” added Ashley. “If they don’t laugh, it’s not funny.”

In publishing, said Roshan, the audience is measured in circulation, which drove the discussion to what panelists agreed was the true motivator: the bottom line.

“Either they buy it or they don’t buy it,” said Roshan.

Sometimes, said Rudnick, studio executives can take the bottom line to incredible lengths. He recalled an incident during the casting of “Sister Act,” which he wrote with Bette Midler in mind. Rudnick said Midler rejected it saying she didn’t want to play a nun, and Whoopi Goldberg was cast. When it came time to cast Goldberg’s love interest, Rudnick said Disney executives panicked over political correctness, debating the merits of pairing a black actress with a black man versus a white man. In the end, producers suggested Latino actor Edward James Olmos. Rudnick quit the project.

The Vignellis talked about the risk aversion they find with corporate clients, Mossimo saying that the players are motivated more by money than passion. He maintained that that fear can be a driving force, arguing, “Risk is food for the soul.”

What about critics? All agreed they could be caustic when taken individually, and valuable when digested en masse.

“You will be driven mad by a single review, whether good or bad,” Warren said. “You will be haunted by that single voice, but if every review says it’s long in the second act, it becomes foolish to ignore it. The key is to find consensus.”

What if the piece is a flop, asked McKinley?

“We wouldn’t know,” deadpanned Rudnick to laughs, adding that there are individuals whose voice he respects. Among those, he said, are his cohorts in the theater world.

“It is so impossible to make a living in the theater that everyone is there for the passion. There is no greater feeling, because there are no other agendas,” said Rudnick.

A far cry from Hollywood, where the PR machine dominates, he said.

After the panel, Rudnick spoke to Gay City News about whether his gay-themed material suffered when studio executives tried to make it palatable for a mainstream audience.

“I was very lucky on ‘In & Out’ that the producer who was also openly gay was very protective of the property and the content,” he responded. “The studio was much more nervous.”

Rudnick recalled an early test screening in which a middle-aged woman said she loved every part of the film, but would not recommend it to others.

“[The questionnaire] said ‘If not, why not’ and she wrote, ‘Against God’s law,’” recalled Rudnick, laughing. “When the studio at times felt the movie was getting too gay, they would use a code, they’d say, ‘We feel it’s getting repetitive.’ Until one day I just said, ‘Well you know, some of us were born repetitive,’ and that seemed to end the conversation. But a lot of movies get homogenized.”

Nahem’s panel series will continue in March 2005 with “New York Dreamakers,” people who moved to the city and realized their dreams. For information about the series, contact him at 212-592-3695 or rn88@rcn.com.