MAGNUS BOOKS

BY DOUG IRELAND | I have, for many years, appreciated Urvashi Vaid as the most progressive and liberationist of the institutionalized mainstream gay movement’s prominentii. Now, based on three decades of sterling activism, she has delivered a stinging critique of those institutions that should be must reading for every queer activist and anyone concerned about the nature and direction of those who claim they speak for all of us.

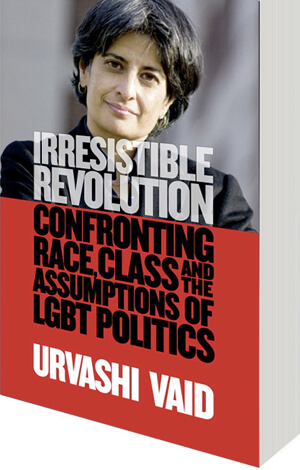

Magnus Books, the three-year old imprint founded by the great Don Weise, a peerless force in queer publishing and a superb editor of queer books for more than 20 years, has just published Vaid’s “Irresistible Revolution: Confronting Race, Class, and the Assumptions of LGBT Politics.” And Vaid does not pull her punches.

“The LGBT movement has been coopted by the very institutions it once sought to transform,” she writes. “Heterosexuality, the nuclear family, the monogamous couple-form are our new normal. In place of activism and mobilization, with a handful of notable exceptions, LGBT organizations have become a passive society of spectators, following the lead of donors and pollsters rather than advocating on behalf of sectors of the community that are less economically powerful and less politically popular.”

Longstanding lesbian leader lays out radical vision re-embracing liberationist path to change

Vaid is right on target when she says, “This impoverishment of ambition and idealism is a strategic error. It misunderstands the challenge queer people pose to the status quo. It shamefully avoids the responsibility that a queer movement must take for all segments of LGBT communities. And it is deluded in its belief that legal, deeply symbolic acts of recognition and mainstream integration, such as admission into traditional institutions like marriage, or grants of formal legal rights within the current form of capitalism, are actually acts of transformation that will end the rejection and marginalization of LGBT people, without deeper and more honest appraisals of the limits of the traditions to which LGBT people seek admission… The LGBT politics currently pursued will yield only ‘conditional equality,’ a simulation of freedom contingent upon ‘good behavior.’”

I also agree with Vaid when she regrets the way in which the gay movement has abandoned the inclusive, liberationist, and anti-racist politics of the 1970s for a much narrower agenda and set of values. “The gay rights focus was historically needed but is a vestigial burden we need to shed,” she writes, adding, “It leads to failure at the polls, is bad political strategy, narrows our imagination, does not serve large numbers of our own people, and feeds the perception that we are generally privileged and powerful.”

The best chapters in Vaid’s new book — her third — concern the problems of race and class. She has marshaled a horde of statistics and studies that show how the institutional gay movement, in its current, all-white incarnation dominated by corporate-dominated thinking, excludes huge numbers of working class and poor queers and queers of color. She decries the undemocratic structure of those institutions, with their unaccountable, self-perpetuating boards of directors free of any membership control, and a pyramidal top-down structure that reduces us to “checkbook activists” — unfortunately, only those of us who can afford to write checks.

This undemocratic movement “is unconsciously (and sometimes consciously) limited to white LGBT people. More often than not, it takes positions that reference the needs and interests of gay men, not lesbians, bisexual, or transgender people. How else can one explain the LGBT movement’s silence on issues that have a clear and disproportionate impact on LGBT people of color” in a country which, the latest census figures show, will be a majority non-white in a couple of years? “How else can one explain the movement’s refusal to address issues of race? And how else can we explain the silence of most mainstream LGBT groups on policy fights on reproductive justice, violence against women, police abuse, and criminal justice abuses?”

Vaid also quite rightly skewers the inordinate influence on our agendas and values of major gay donors and foundations, also unaccountable to anyone, who devote their funding to a whites-only politics of access while withholding support from groups that engage with race and class issues.

Given Vaid’s intimate knowledge of the gay institutional world garnered in her 30 years of activism — including stints as the executive director of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, as founder and head of its valuable Policy Institute, and in major posts at the Ford and Arcus Foundations as well as the ACLU, attention must be paid.

Vaid frankly acknowledges the fundamental cleavage in the gay movement between the left and the “center-right” (think Human Rights Campaign), the latter made up of groups that seek the comfortable, self-censorious goal of “belonging” within corrupt and exclusionary institutions without ever taking on the responsibility of challenging them. She decries the backroom politics of deal-making that excludes most of us from participation. And she regrets the abandonment of the subversive “otherness” that is at the heart of queer sexualities.

“Queer presence — LGBT life in its widest range — builds curious and sometimes marvelous communities,” Vaid writes, including “subcultures that turn pain into caring; institutions that work to deliver services; resilience and humor instead of bitterness and violence; extended kinship structures that deliver emotional and material support but that are independent of blood ties; exceptional acts of generosity and affiliation with those who are social and political outcasts. Instead the LGBT movement tries to conform these creative forms of expression, to run from the freedom we have had to build unique lives, and submit ourselves to the confining forms that propriety, adherence to tradition, or legibility in this form of capitalism demands.”

Vaid was trained as a lawyer; unfortunately, she writes too much like one. I find her politics so congenial that it pains me to remark that I wish she wrote a tad more gracefully. There’s another problem with this book: it is essentially a collection of the texts of speeches that Vaid has given over the last few years, which have been but little rewritten and are capped with anecdotal when-where-why introductions explaining how they came to be made. But a speech is not an essay, and this collection is a bit disjointed, uneven, and sometimes repetitive, as Vaid repeatedly makes the same points in several speeches. Some of her turns of phrase in these speeches are a might hortatory for the printed page.

But these are quibbles, for this is a thoughtful, courageous, and important book. Vaid does not shrink from self-identifying as a “radical,” a “socialist,” and a “liberationist.” These are not popular labels these days for those of us — and I include myself here — who accept them. And she calls for nothing less than a total restructuring of the gay movement and a return to the values with which gay liberation began.

“LGBT people rarely speak to America in a universal language,” Vaid declares. “When we do, it is achieved by dumbing down, by pretending to be who we are not, rather than honestly addressing the anxieties and fears of heterosexist society… The moral values and vision that ground LGBT people are appealing and healing to the world. If we only talk about the particulars of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), or the destructive impact of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), as matters that affect LGBT people alone, we miss the opportunity to transform the very idea of national identity and of Constitutional Freedom.”

I don’t agree with every one of Vaid’s formulations. For example, when she insists that a new queer agenda must include promotion of human rights around the world, starting with[emphasis added] strong leadership from the State Department to promote LGBT human rights,” I have to say: No, we must (as I have often written in these pages) start with ending the isolationism of the gay movement and its refusal — unlike its European counterparts — to engage in international queer solidarity with those more oppressed than we are.

And strategically I can’t go along with her notion of creating “an LGBT party,” an idea she tosses out without any amplification or rationale.

But I’m in overwhelming agreement with Vaid’s diagnosis and with most of her prescriptions. And it is to be devoutly wished that this book will contribute to a major new debate re-examining the principles and values that guide our gay institutions. Is anybody out there listening? Let’s hope so. Read this book!

IRRESISTIBLE REVOLUTION:

CONFRONTING RACE, CLASS, AND

THE ASSUMPTIONS OF LGBT POLITICS

By Urvashi Vaid

Magnus Books

$21.95, 236 pages