Carrie Davis, of Center’s Gender Identity Project, weighs gains, obstacles

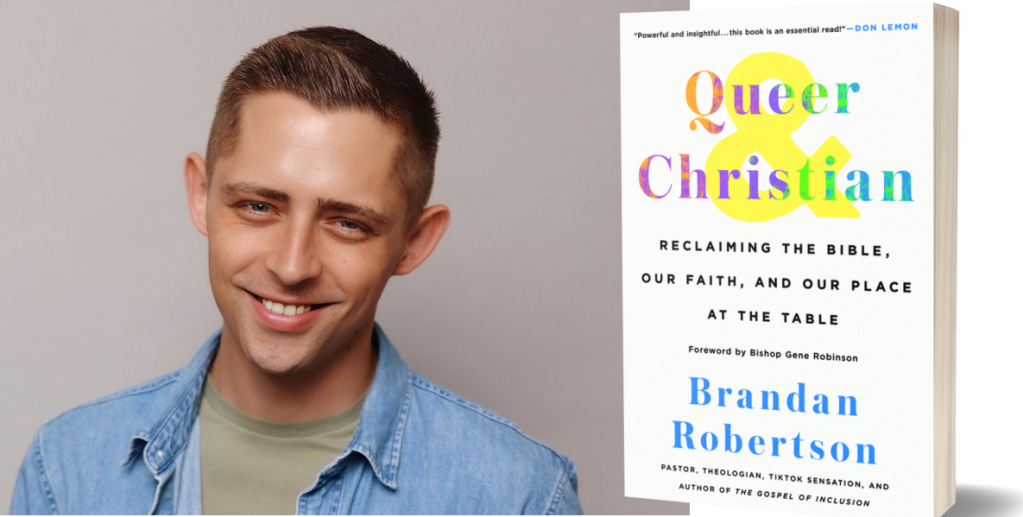

Sitting in her small office at the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center, Carrie Davis remarked on the progress that transgendered people have made.

“It’s been a big shift,” said Davis, coordinator of the center’s Gender Identity Project (GIP). “It has been a shift from seeing transgender as a pathology to seeing transgender as an identity.”

The most recent evidence of that shift came when the city’s Commission on Human Rights released guidelines that are meant to aid employers and businesses in implementing the 2002 city law that bans discrimination based on gender identity or expression.

“I think they are a first step, a huge first step,” said Davis who was part of a group of gay and transgendered activists who helped write the guidelines. “I think we did a good job of getting people covered and protected.”

The law, which bans discrimination in employment, public accommodations and housing, is generally perceived as protecting transgendered people, but it could also be used, for instance, by butch women or nelly men.

The city law is part of a broader effort to eventually get New York State to enact similar protections. Davis said that strategy was conceived in 1998 at the first meeting of the New York Association for Gender Rights Advocacy.

“Our goal in getting state protections was to get local protections first,” she said.

Davis has worked at GIP since 1998, which is long enough for her to have witnessed her employer change its name to include “Bisexual and Transgender.” She praised gay community groups for their efforts at including the transgender community.

“I see a very strong movement to integrate,” she said. “I think these organizations work their asses off to make these connections.”

Davis also observed the exclusion of transgender protections from the 2002 state law that banned discrimination based on sexual orientation. That exclusion came when the bill was conceived, more than 30 years before it was enacted, Davis said.

“The essential mistake occurred in the inception, not in the implementation,” she said. “It’s regrettable and yet, at the same time, it’s a very powerful thing having it passed.”

Her work at the Center has changed as well. GIP started 15 years ago as a program to help trans men and women with drug and alcohol problems.

“Trans women were being told that they weren’t woman enough to obtain recovery services,” Davis said. “There was a corollary with trans men.”

GIP still offers drug and alcohol counseling. It has added HIV prevention programs and groups for men and women who are weighing sex reassignment surgery and for those who may be exploring an identity that rejects the binary of male or female. There are also groups for the partners of transgendered people and for trans folks who are parents.

Then there are the social events that draw anywhere from 60 to 160 people every month.

“To have that many people show up, we must be doing something right,” Davis said.

GIP was originally run by peer counselors. Beginning in 1998, the staff increasingly has held advanced degrees.

“That’s when this organization moved away from being a paraprofessional organization to a professional one,” said Davis who earned her master’s in social work in 2003. “We no longer had people operating groups who did not have a professional degree.”

Davis has considered pursuing a Ph.D., which would enable her to do more research, but the time and the expense would be too great.

“In this setting, it gets you the ability to be the primary investigator for research,” she said. “I know that it’s an exhausting process and I can’t afford to stop working.”

While Davis reluctantly discussed her life outside of work, parts of it were in evidence in her office. A women’s basketball team she plays on won trophies in 2002 and 2003.

“I was our center until we got someone taller,” she said.

There are some skilled players in her Brooklyn basketball league.

“The people that play are college-level and they make me look really bad,” she said.

Davis also plays on a softball team that won an award in 2002.

“I’ve played on the Titans since I began playing sports at age 42,” said the 45-year-old Davis. “Sports are a huge part of my personal and social life.”

There are also bouquets of roses displayed in her office that she must have received some time ago. They have all dried out.

“I have a romantic life,” she said, without elaborating.

Before joining the Center, Davis was a successful architect. She proudly shows some of the homes she designed though she insisted that the name of the firm she once worked for not be mentioned. She left that industry, in part, out of disillusionment, but also because it no longer welcomed her after she transitioned.

“Initially, it was the result of transitioning,” she said “Since then, I have had many offers to return and I have declined… I was becoming a designer of rich people’s houses. I was trained to see architecture as a form of social change.”

Now, with some six years of experience at GIP, Davis is increasingly called on to teach others what she has learned.

“One of our current goals is to export the experience we have developed over the past 15 years,” Davis said.

That is happening in several ways.

Davis regularly trains service providers on how best to serve transgendered clients or how to comply with the city law that bans discrimination based on gender.

Typically, the requests for training come when an agency has encountered a problem or when its sees an increase in transgendered clients.

“They have a client who wasn’t served properly or they see a trend,” Davis said.

She estimated that she delivers one of these trainings every two or three weeks.

“If I just answered the phone and dealt with that, it would be half my job,” she said.

The trainings can range from a basic transgender 101 to a more advanced “how to interview, how to offer services,” according to Davis.

“My goal is to always connect it to whatever it is they do,” she said.

Eight to ten social work interns who work at the Center each year see how that institution has responded to its transgendered clients and employees. The interns “spread the gospel” when they move on to other employers, Davis said.

Still, when considering the advances for transgendered people, Davis noted that not all of them have shared equally in the benefits of those advances. For the poorest, for those who may be struggling to find employment or with drug or alcohol problems, the changes may not have happened yet.

“I think that for some people it has happened quickly,” she said. “For others, those with the least resources, it has moved more slowly.”