Whitney tackles whether or not the lens determined the course of modern painting and art

It would be difficult to overestimate photography’s impact on contemporary art, whose star these days is completely ascendant, to the extent that other mediums, particularly painting, look to photography for inspiration. In fact, photography’s influence has been so prevalent that Jerry Saltz recently called for a moratorium on paintings so inspired.

In its defense, photography has been the medium of choice for an entire generation of artists interested in exploring and exposing structural forms. One group, led by Cindy Sherman that includes Lyle Ashton Harris, Lorna Simpson, Rineke Dijkstra, and Collier Schorr, explores the structures of identity, while another group—in the tradition of the Bechers—that includes Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Thomas Demand, and Candida Hofer, explores the often-hidden structures within the social or natural landscapes chosen as subjects.

How and when photography crossed over from being a commercial or popular medium into one more frequently used and accepted by the art establishment is difficult to pin down. That transferal clearly happened somewhere in the 1960s and 70s, but then again almost all contemporary art forms made a similar journey in those seminal days.

Despite the chronological ambiguity, however, what is known is that in the wake of Minimalism and Conceptualism there has been an enormous cacophonous body of artistic production that tends toward personal experience and smart critical distance, both of which are stances ideally suited to photography.

“Evidence of Impact: Art and Photography 1963-1978” modestly attempts to flesh out some of the contours of photography’s first foothold in contemporary artistic practices.

Amazingly, considering its limited breadth, the exhibit comes at its subject from three different perspectives.

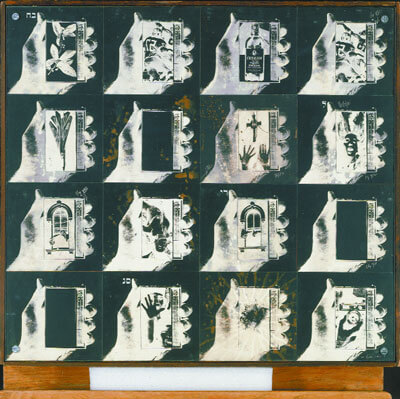

First, and most thoroughly, the photo-based work of artists whose primary medium was not photography is presented. This group includes Paul McCarthy, Jay DeFeo, Robert Smithson, Charles Ray, Dennis Oppenheim, Mel Bochner, Wallace Berman, and Adrian Piper. Smithson’s piece, originally published in “Artforum,” that documents a day trip to the Meadowlands, reveals a poetic grace, not surprisingly.

Similarly, a group of photographs by the groundbreaking Mel Bochner examines how Vaseline and shaving cream interact differently with color and light. Bochner’s piece is a meditation on the very materials of photography and is thereby one of the stronger installments in the exhibition.

Adrian Piper’s 14 self-images in various stages of undress, during breaks in her studio of readings of Kant, raise haunting questions. The piece by Paul McCarthy derives its significance primarily from the actual performance it documents.

A second grouping contains work that documents in starkly straightforward terms the transformation of the American West from the time of expansion to the present day. Photographs by Stephen Shore, Joe Peal, and Lewis Baltz are closely tied to the contemporaneous archaeological work of the Bechers. The inclusion of these three particular artists seems to indicate an uncertain moment when photography unwittingly crossed a line from documentation into art, but the assertion is made less than effectively. Although the work is credited as a precursor to that of Joel Sternfeld, for example, the delineation is not particularly compelling, perhaps due to the limited context of the exhibition.

Three wonderful photographs, stuck together mid-way through, provide the greater part of the exhibition’s visual pleasure as well as its third thematic focus. Two New York urban street scenes, one by Lee Friedlander and the other by Gerry Winogrand, hang next to a fabulous Diane Arbus portrait of a Westchester family. Each shot is hip, smart and complex.

The Arbus print strikes right to the core of suburban artifice and boredom in a way that brings to mind the later work of Eric Fischl, yet another painter heavily indebted to photography. A trip to the Whitney is well worth the effort for this one little photograph.

The reason for the inclusion of these three photographs within the larger context of this exhibition, however, remains unclear. Did these photographers gain artistic recognition while photography still had not achieved its full status in the art world, thereby staking out precedence? What about the photographers Stieglitz or Man Ray, two art world insiders long before this?

While scratching the surface of a number of fascinating ideas, this exhibition leaves unanswered many questions.

A majority of the exhibition’s artists are strongly affiliated with Conceptualism, a movement by definition that was defined by the primacy of concepts over medium. For these artists, the medium was merely at best a vessel for the concept. It is too risky to attempt to anchor the importance of any medium—especially one based on image—in these choppy waters.

Then, there is a problem of scope, which is not resolved by one tiny exhibition room that leads to gaping holes in the narrative. Leaving aside the work of Ed Ruscha—the wall text notes that this exhibition is meant to accompany a forthcoming one of his photographic work—the absence of work by Andy Warhol, John Baldessari, and Bruce Nauman is egregiously noticeable.

Contemporary imagery, both commercial and artistic, is redolent of photography’s impact on art, even in “Evidence of Impact.” Yet, if photography hit like a giant meteor, this show concentrates too closely on the moon dust, rather than on the crater.