Director Nathaniel Kahn’s documentary “The Price of Everything” focuses tightly on the art world, but in depicting a world where everything is commodified and painters who aren’t hardcore careerists watch others make money from their work without benefiting themselves, it says a great deal about the state of American culture in 2018.

An art historian approaches a Jeff Koons sculpture placed outdoors in a museum and complains that it represents “a glittering compromise with commerce,” feeling particularly repulsed by its slickness. But while the glitter only shines for those of us who are as wealthy as Koons, compromise with commerce defines American life right now.

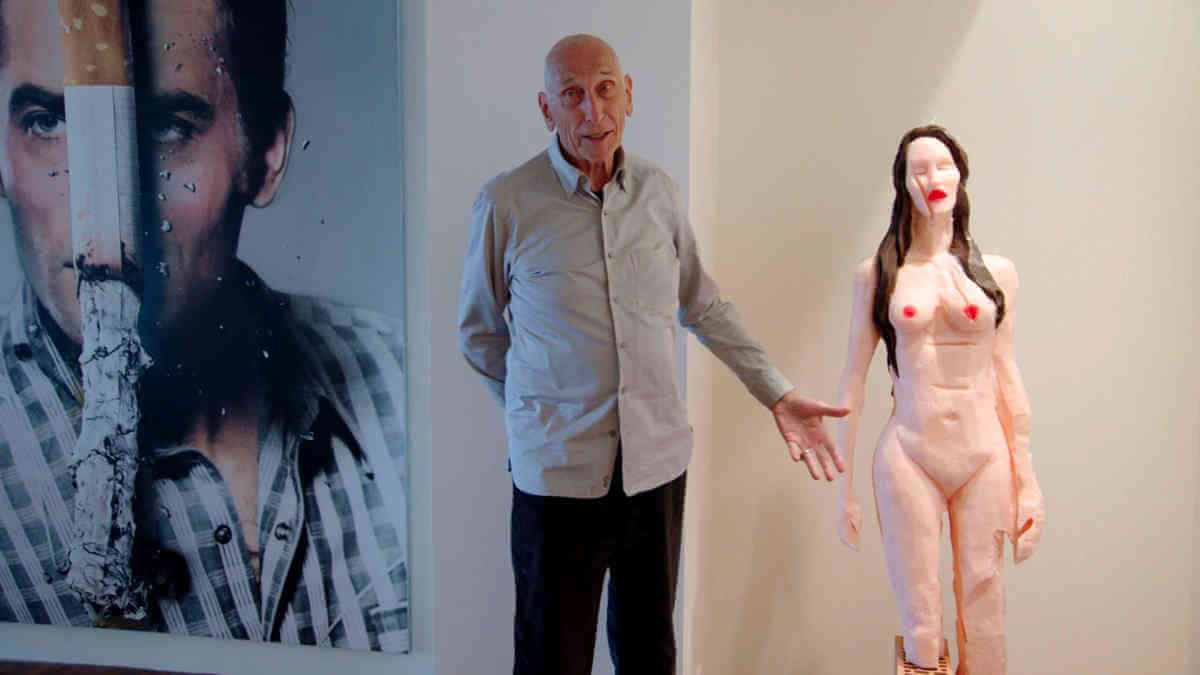

“The Price of Everything” isn’t interested in demonizing anyone as an individual, but it’s very clear about what artists it values and which ones it doesn’t. Koons comes off as a fairly charming and articulate person, though the film points out his background as a Wall Street salesman, complete with clips of “The Wolf of Wall Street.” Kahn makes a case for Koons’ work as the voice of neoliberalism’s emptiness. It’s probably no coincidence that the name of one of the painters he does celebrate — who rejected the temptation of success in the 1970s by departing from his formula of dot-based art and compares his ambitions to those of Mozart and Beethoven — is Larry Poons, which rhymes with Koons.

People who know nothing about art history and its context commonly dismiss the whole of abstract art, write off Cubism as ugly, or claim they could make the equivalent of a Jackson Pollock painting themselves. Given how critical “The Price of Everything” is toward the world of art fairs and auctions where paintings sell to private collectors for millions, often disappearing into rich people’s houses and away from public view, it would have been facile for Kahn to fall into a similar trap. In fact, he doesn’t really engage with the aesthetics or the historical place of Koons and other artists the film criticizes, like Damien Hirst. One could say that by not actually working directly on his own paintings and having a team paint them according to his instructions, Koons is debunking the myth of the male genius that contributed to Pollock’s self-destruction. But “The Price of Everything” offers lots of first-hand evidence that he’s just offering a middlebrow celebration of American vulgarity to millionaires.

Kahn has more interest in praising artists like Njideka Akunyili Crosby, a Nigerian-born woman who only received her MFA from Yale seven years ago. But even if she talks about working at a relatively slow pace because she wants to have time to experience enough life to inspire her paintings, she’s part of the art world’s games. He shows one of her paintings selling at an auction, with the price gradually going up to $900,000. He cuts to Crosby watching the auction on her laptop, looking blank and then laughing. She reveals that the person who bought the painting from her paid a relatively low price and then flipped it at a high profit, without her direct benefit. Crosby seems to have a healthy attitude about this — she doesn’t feel ripped off, saying she’s more concerned about protecting her long-term future. But still, rich white people are making more money off her work inspired by African life than she is right now.

Although Kahn’s voice can be heard talking to his subjects, he says that “The Price of Everything” is “composed not of interviews, but of scenes — encounters — through which we explored a world vastly more puzzling and contradictory than I ever imagined.” Poons comes as close as one can to living off the grid while still participating in the art world, but he’s now elderly and his deafness suggests growing frailty.

Most of the other artists depicted in “The Price of Everything” are up for competition, but resigned to the cruelty of the marketplace (as well as its sexism and racism). This describes every aspect of American life, except that this film respects the potential for beauty and social reflection contained in art. It’s also generous enough to end with the image of a mirrored ball created by Koons. I don’t think the source matters as much as the resonance of this work as a metaphor. To pick a quote from one of the film’s earliest moments, “You only protect things that are valuable.” Kahn’s “The Price of Everything” has a lot to tell us about how that value gets determined.

THE PRICE OF EVERYTHING | Directed by Nathaniel Kahn | HBO Documentary Films | Opens Oct. 19 | The Quad, 34 W. 13th St. | quadcinema.com