![The 1912 “Mother Goose as a Suffragette” includes a stinging little poem about how voting rights were reserved for “My husband [who] was dumb.” | KELSY CHAUVIN](http://gaycity.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CHUAVIN-suffrage-mother-goose-IS.jpg)

These are just a few of the cold, hard facts we should remember when viewing the new Hunter College exhibit, “Women Take the Lead: From Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Eleanor Roosevelt, Suffrage to Human Rights.” Opened on January 14, it’s the first special exhibition organized by the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute at Hunter, on East 65th Street, since the space reopened six years ago. And what a perfect fit it is for this historic gathering place, once home to civil rights champions Franklin and Eleanor, a gift from FDR’s mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt, circa 1905, the year of their marriage.

The exhibit brings together a collection of rare original artifacts used in the early 20th century to promote voting rights for women. Among them are about 75 posters, broadsides, pamphlets, photographs, and manuscripts that reveal political messages unique to the era preceding the 19th Amendment. That monumental reform was approved in 1920, at long last adding to the Constitution: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied… on account of sex.”

New exhibition honors feminist leaders from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Eleanor Roosevelt

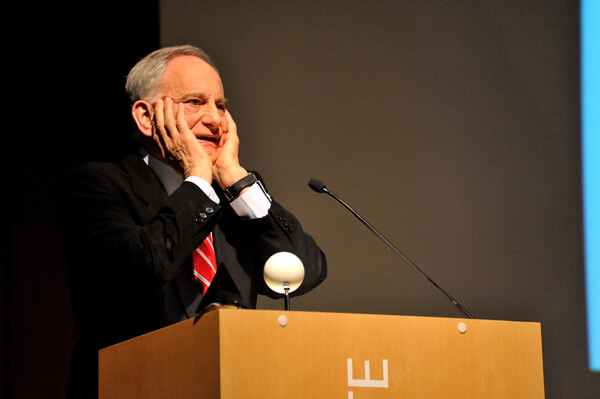

While the exact usage of many of the two dozen posters displayed here is unknown — they were possibly pasted to walls or used in marches — award-winning historian Harold Holzer, the recently named Jonathan F. Fanton Director of the Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute, calls them “the tweets of their day, directed at men to stop hogging power.”

“They are pithy, declarative, and humorous,” said Holzer at the show’s opening. “They’re enjoyable ways to share the message.”

He pointed out posters that work as part of a series, with messages about practical issues like laundry and childrearing that spoke directly to the male voting block’s domestic concerns. Many of them also clearly try to make a rational, intelligent argument for suffrage, like these choice examples:

“You trust women with your children, can you not trust them with the vote?”

“The welfare of the State as well as the home demands votes for women.”

“Who would mind the baby when the woman goes to vote? The one who minds it while she goes to pay her taxes.”

Most of the extremely rare pieces that comprise “Women Take the Lead” come from a special loan by the Dobkin Family Collection of Feminist History, and the exhibition is supported by a grant from Roosevelt House board of advisors member and Hunter Foundation trustee Elbrun Kimmelman and her husband Peter. The privately held Dobkin Family Collection was built over 25 years by New York philanthropist Barbara Dobkin (now overseen by her daughter Rachel) and chronicles women’s political and domestic experiences and achievements.

With posters dating to the 1912 presidential election year, some of these materials have never been shown together publicly. Along with them are a cross-section of artifacts related to women’s civil rights, including an early printed copy of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s “Declaration of Sentiments” from the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention; an original manuscript on family planning by birth control activist Margaret Sanger; and the hand-edited 1938 Nobel Prize acceptance speech of novelist Pearl S. Buck — the first American woman to win that honor.

Appropriate for the venue, Eleanor Roosevelt’s work also is well represented. There are letters she wrote to her family and prominent figures tracing her evolution as a human rights leader from her time as first lady of New York and then the United States, and during the decades that followed. She is shown in various photos, including one with New York’s fierce Representative Bella Abzug, who famously said during her successful 1970 campaign: “This woman’s place is in the house — the House of Representatives.”

“Women Take the Lead” comes at an especially discordant moment politically, with presidential primaries looming and divisive candidates polling higher than what many New Yorkers may have anticipated even in a worst-case scenario.

“In a year in which two women are seeking the presidency of the United States and women around the world are raising questions related to opportunity and empowerment, this is the perfect time and place to take renewed inspiration from the Suffrage Movement, still barely a century old,” said Holzer.

Many of the exhibition’s pieces offer straightforward slogans that balance both earnestness and humor — a sign that many suffragettes saw the irony of running a home they weren’t legally able to govern. Or perhaps they were just using humor as a strategy to reach uneducated men who, paradoxically, held all the power to approve equal voting rights. One of the most amusing of these artifacts was the 1912 booklet, “Mother Goose as a Suffragette,” where this rhyme sums up the situation of the day:

“I had a little husband

No bigger than my thumb;

Though I was a college graduate

My husband, he was dumb.

I earned the money we lived on

And ran the house beside,

But when it came to voting

I must humbly step aside.”